Eileen Cunis, 67, makes banners for churches. Not those primitive and graceless felt-and-burlap banners that dominated liturgical decor through the ’60s or ’70s, but thoughtfully crafted, dignified works of art produced by a woman who just wants to walk through whatever door the Lord has opened for her.

One of Cunis’ pieces, a processional banner of Mary Mother of the Eucharist, was recently accepted for the National Eucharistic Revival Art Exhibit, and it will travel from Connecticut to Indiana. It is a shining, intricate, iconlike work with many layers of fabric and brocade carefully pressed, folded and sewn into position, the faces and hands of Mary and her baby delicately rendered in paint.

Wading into iconography

As delighted as Cunis is to have her fabric work honored, she’d really rather be painting. She prefers the freedom and flexibility of working exclusively with paint, and she’s starting to wade into the deep waters of iconography, with its profound theology of light.

“I would love for a priest to say, ‘I have this big wall and I want you to do a big mural, and it’s going to be in the church for 50 or 100 years,'” she said. But it all comes down to how the Lord is leading her right now.

Right now, she’s just finished a set of four tapestries for Sacred Heart Church in Bloomfield, Connecticut, a building that had some vast, empty spaces to fill. It’s a gymnasiumlike structure, and that’s not just a coincidence. The church was built in 1962, when Catholicism in the United States was still burgeoning. The congregation assumed their parish would continue to flourish and grow, so they built the church intending to eventually convert it into a gym for the Catholic school.

“It just didn’t happen,” Cunis said. “People were caught flat-footed, and the gymnasium church remained the church.”

The school closed in the ’80s, a nearby church also closed, and the large, simple structure of Sacred Heart became the main church building for the congregation. It had been decorated and made suitable for worship, but still had a rather bleak facade on the apse wall.

The pastor saw Cunis’ work in a local shop, and a lightbulb went on. The gray space has now been transformed by a small host of angels rendered in shining fabric.

Cunis’ first banner, though, wasn’t designed to enliven a large space, but just the opposite.

“[That] church didn’t have much room for permanent art,” she said.

They wanted to use well the space they had, and also to be able to change the decoration according to liturgical season. The pastor asked the congregation if anyone could help, and Cunis, who had only been Catholic for a few years, stepped up.

‘Whatever is called for’

This “whatever is called for” approach is one that has served Cunis well, in her artistic life and her spiritual life in general. She grew up agnostic, and it wasn’t until she moved to New Hampshire for college that she really met the Lord, through a nondenominational charismatic student fellowship group.

“All of us were groping, seeking, trying to find the direction the Lord had for us,” Cunis said.

She also met her now-husband, a poorly catechized Catholic who was also in the group. They both deepened their faith, got married and went on to have three children, whom Cunis homeschooled.

She and her husband weren’t happy in their current faith. They were disillusioned by the tendency of Protestant groups to squabble, split and start new churches.

Her husband’s family encouraged them to consider Catholicism, but Cunis recalls that, at the time, she thought the Catholic faith was simply a matter of going through the motions.

“My ignorant impression was that most Catholics didn’t have a real relationship with Christ,” she said.

Then one day, they attended a Catholic wedding.

“I was blown away with how it was all scriptural,” she said. “It was a beautiful thing. I was so touched by the beauty of the Mass itself, the prayers, the understanding of what marriage is, the reverence for God. We could see life there.”

The liturgy itself was nothing especially elaborate — no incense, Latin, or musical grandeur.

“But the priest was a wonderful man who truly loved God, and it showed. The presence of Jesus came through very powerfully,” she said.

A Church that celebrates art

At the same time, her kids were growing older and more independent, and Cunis felt her days opening up. It was the late ’90s, a few years after her conversion. Although she had always loved making art, and used it as much as she could while teaching her kids, she was still nagged by the antiart attitudes prevalent in her old “Bible Christian” days.

“If I illustrated Bible stories, you could justify that,” she said.

But the arts in general had been treated with suspicion, and she never thought she’d have a future as an artist. When the pastor of that small church asked the congregation for help, she thought, “Well, I can sew,” not thinking she was doing more than filling a practical need.

So she did. She also designed most of the banners her group made. Cunis also took advantage of her newly freed-up time and enrolled in an online master’s degree program in theology.

She was delighted to learn, in the course of her studies, that the Catholic Church not only accepts artists, but celebrates them. This was in the early 2000s, shortly after John Paul II wrote his short but groundbreaking letter to artists.

“I continue to go back to John Paul II and what he wrote about art. It wasn’t extensive, but it was powerful. He was singing from the mountaintop that this is what speaks to us, this is what we need,” she said.

She ended up writing her thesis on the vocation of the Catholic artist. The idea of being sent out on a mission spoke to her powerfully.

Work of human hands

“When I started [making liturgical art], I looked at it with a workmanlike attitude: There’s this thing that’s needed to fill this space, and we’re gonna execute it,” she said.

Now, she is more in awe that she has the chance to create art that will not only lead people to God, but will be in his presence at Mass.

For how long? She can’t say. She has thought about the longevity of her fabric pieces.

“They won’t last forever. There’s entropy; things will fade, and will stretch or droop,” she said.

What they will look like in the distant future, she just doesn’t know. But the same is true for any work of human hands.

“I guess I’ve focused on what is asked for right now,” she said.

An arrow that strikes the heart

Benedict XVI spoke of beauty as an arrow that strikes the heart, and she has felt that.

“I’m just kind of doofin’ along in my workshop, pulling out threads and making mistakes and getting mad at myself. But I’m just going by grace, and the Lord is using it,” she said.

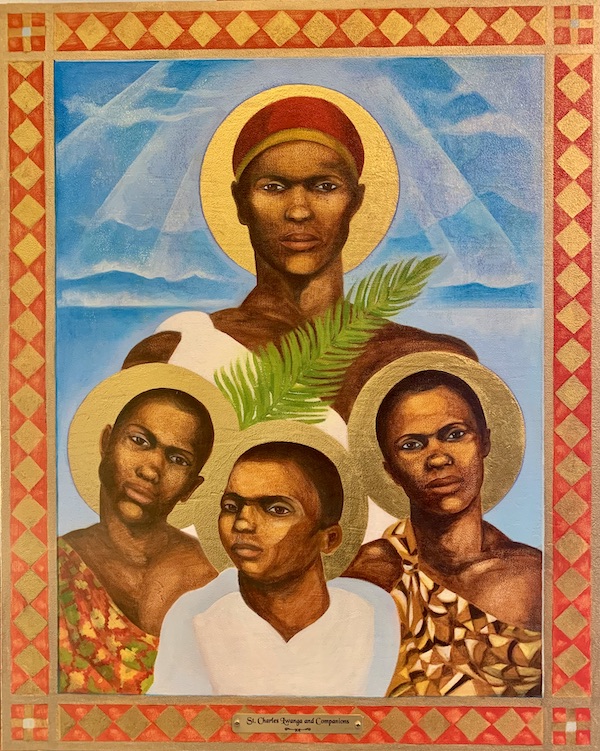

This year will be her 30th anniversary of entering the Church. She is painting striking pieces depicting the saints and other sacred images, and she has illustrated two books.

“It’s about waiting for what is the call today for me to do,” she said.

Whatever that call sounds like, she will try to follow it, as long as it’s from Jesus.

“That’s what really drew us into the Church, was finding out that Jesus really is present in the Eucharist. When I understood that, that’s where I wanted to be. If this is what he started, I’m going,” she said.