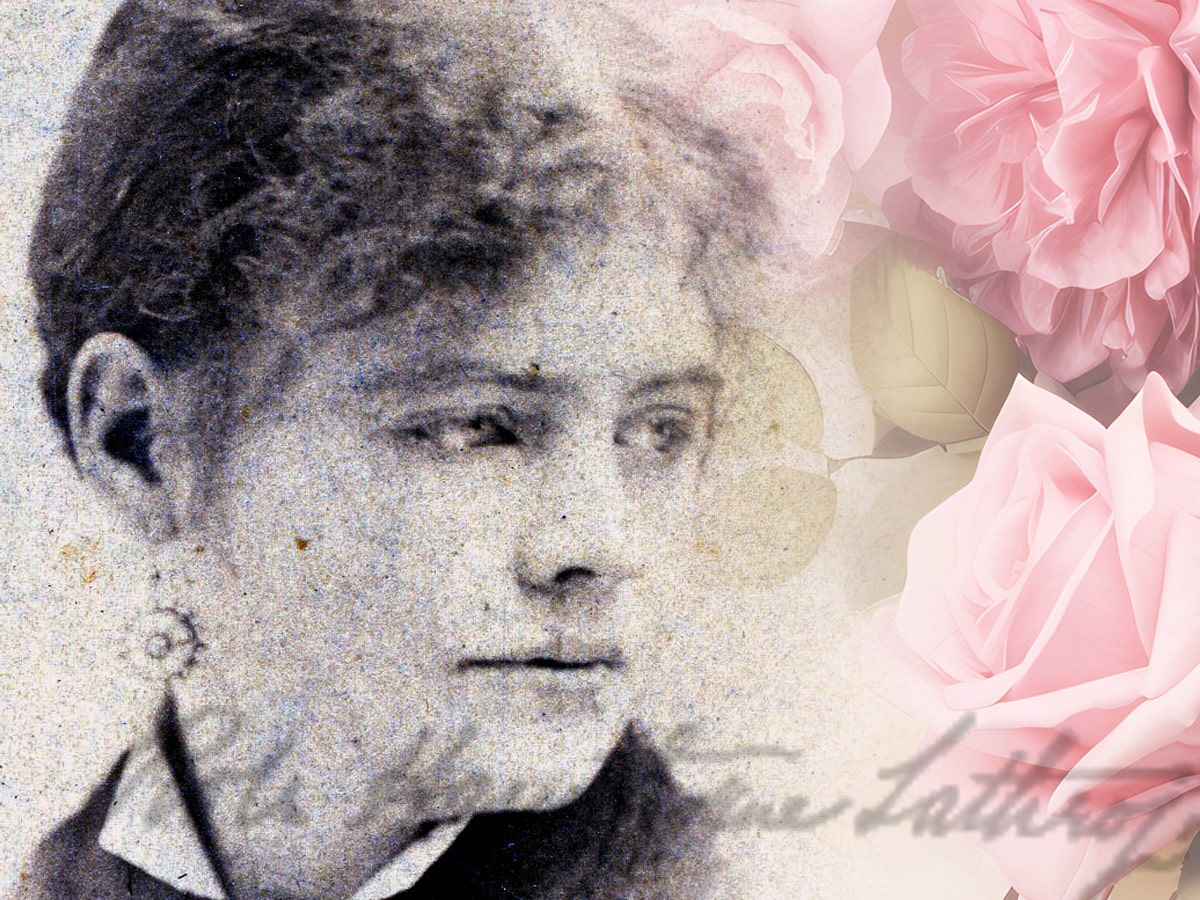

Little Pessima, Rosebud, Sweet Briar Rose, Mrs. George Lathrop, Mother Mary Alphonsa — and as of March 2024, Venerable Servant of God Rose Hawthorne. The youngest daughter of Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne was called by many names during her life, and her journey to being declared a venerable servant of God was not a simple one. Like all of us, she knew many joys and sorrows during her lifetime. We are all searching for love in one way or another and Rose was no different. The real story of her life is how God’s love worked in and through these joys and sorrows — leading her from a loving New England childhood to finding her deepest joy in being a different sort of bride and mother — a spouse of Christ and spiritual mother to his sick poor in the tenements of New York City and the hills of Westchester County.

Rose was born May 20, 1851, the third child of famed author Nathaniel Hawthorne and his remarkable wife Sophia (née Peabody). Both parents contributed exceptional intellectual gifts and a dedication to education for their children. More importantly, they offered their children an example of profound love and deep devotion to one another, making a loving and happy home. Theirs was a marriage of equals in mind and heart, by all accounts.

A happy childhood

When Rose was born, her family had just moved from Salem to Lenox, Massachusetts. Many years later, in a letter for Rose’s 16th birthday, Sophia lovingly described those early days:

… I do not know as there is yet any language in which I can convey to you an adequate idea of how I love you and have loved you since I first saw your tiny form. … Your babyhood was most lovely and sunny. Grandpa used to declare that you did not know how to cry. You showed the most philosophical patience in attaining your ends. If one way failed, you tried another way, and all in perfect quiet and repose. … This calm intent outlook which you maintained, before you could speak, won for you the title of Lord Chancellor the Dispenser of Equity. … You were very critical in your observations, and one day, when you did not fancy the appearance of Grandpapa, he could not induce you to pass over the described line, till he took out his watch, when with protesting, dignified air, you condescended to approach. I think you inherited from Papa this immitigable demand for beauty and order and right, though in the course of your development it could make you pettish and unreasonable. I was always glad you had it, because I know the impatience and crossness it often caused, would prove a transient phase. …

As one can see from this letter, Rose had extremely loving parents. Nathaniel was equally as affectionate toward her in his letters and no doubt in daily life, although the success of his most famous novel, “The Scarlet Letter,” and his assignment as American consul left him less time with her than he had had with his older children. He was the one who lovingly addressed her as “Dear Little Pessima” and gently corrected her for hitting her brother and sister when she was 4 years old. Another letter began, “MY DEAR LITTLE ROSEBUD,– I have put a kiss for you in this nice, clean piece of paper. I shall fold it up carefully, and I hope it will not drop out before it gets to (you).” When she was 5, she wrote her first letter to him. In large cursive writing, she tells him: “dear papa, darling, sweet, dear, I have written it. 1856. Rose.”

A new life abroad

In 1853, the family moved to Liverpool, England, as Nathaniel began his new position as American consul. Five years later, the family left England and traveled around the continent, including a stint in Italy, where Rose was immersed in Catholicism. By 1860, they were back in New England and settled once again in Concord at their old home, the Wayside. Upon their return to the United States, Nathaniel’s health began to decline without any perceptible reason. On May 19, 1864, the day before Rose’s 13th birthday, he died of this unknown illness, which some now speculate was stomach cancer. After this tragic loss of a beloved husband and father, Sophia did her best to make ends meet, educate her children and cope with her own grief with a love and faith that was remarkable. In her letters, she beautifully expressed both her depth of sorrow and her certainty that she would see him again in the afterlife. Rose’s schooling was paid for by a family friend who, in return, enjoyed the company of the young Rose while she was in school. Sophia wrote to her sister in 1868, “Rose is now in (school), and Mary Loring’s aid in this important matter has relieved me of a great anxiety and trouble. For Rose is hungry to learn and it seemed cruel not to give her a chance.” Sophia always saw in her youngest daughter a hunger for knowledge, beauty and truth and encouraged her pursuit of these goods. In the same letter for Rose’s 16th birthday, Sophia wrote:

I knew that religious principle and sentiment would surely render you at last gentle and charitable to the shortcomings of your fellow mortals. … And this will lead you to the heights of being at last. Whereas if you were easy and indifferent, you might deteriorate, and lack the exquisite felicity which comes with the exquisite pain of a noble fastidiousness. … When we know ourselves, we can be kinder to ourselves, as well as more severe. I have always felt that it was most important for such a mind and character as yours that you should be truly religious. GOD alone can rule in your heart. … But you must have the highest motives for action. …

It is remarkable to see how well Sophia knew her youngest daughter and the depth with which she provided advice, encouragement and gentle correction.

A challenging marriage

For financial reasons, Sophia decided to move with her children to Dresden, Germany, in 1868. Both of her older children, Julian and Una, also needed a change of scenery after their own broken relationships. Rose was transferred to a new school in Dresden, where she was not very happy. Although she did not excel in the painting or music she was learning, Dresden was still an important moment in her life — she was once again exposed to Catholic culture, writing beautifully about how hearing the Stabat Mater affected her. It was also where her family became friends with the Lathrops, another American family living in Dresden, that had a son Rose’s age — George. In 1870, both families left Germany because of the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War and settled in London. Tragedy struck the Hawthorne children again, however, in 1871, when Sophia came down with typhoid pneumonia and died in February. Seven months later, to the shock of her family and his, Rose and George were married in St. Luke’s, an Anglican church in Chelsea. Since Julian’s original plan was for George to accompany both Una and Rose back to America after their mother’s death, a sudden marriage and Una’s decision to remain in England infuriated Julian and upset the extended family as well. The Lathrops were not too pleased by the situation either, and so 19-year-old George and 20-year-old Rose began their married life happy between themselves but under a cloud that did not clear quickly or completely over the years. The two had a great deal in common — a love of writing, fathers who had both served in diplomatic roles, living abroad, lively minds and strong personalities — and no doubt Rose hoped for a marriage like her parents had enjoyed.

Once back in the United States, George and Rose moved in with his mother and then moved around until finally settling in Rose’s childhood home, the Wayside. Their married life was challenging despite their affection for one another — George’s professional success but frequent job changes, frequent moves from one place to another, the birth of their only son, Francis (“Francie”), in 1876, the death of Rose’s sister, Una, in 1877, their son’s sudden death from diphtheria when he was only 4 years old, in February 1881. His death did not help their marriage, which was, at times, sorely tried by their strong personalities and George’s struggles with intemperance. Although Rose never explicitly wrote about more than his “illnesses” in her letters and journal, her niece, Hildegarde, wrote more clearly in a later article, where she recounted, “After that blow (Francie’s death) there was never much hope for them as man and wife. During the following months I came closer to Aunt Rose than ever before. … Yet for twelve years more George and Rose lived together, quarreling and making up, until George became so violent and dangerous in his cups that at last his wife left him forever.”

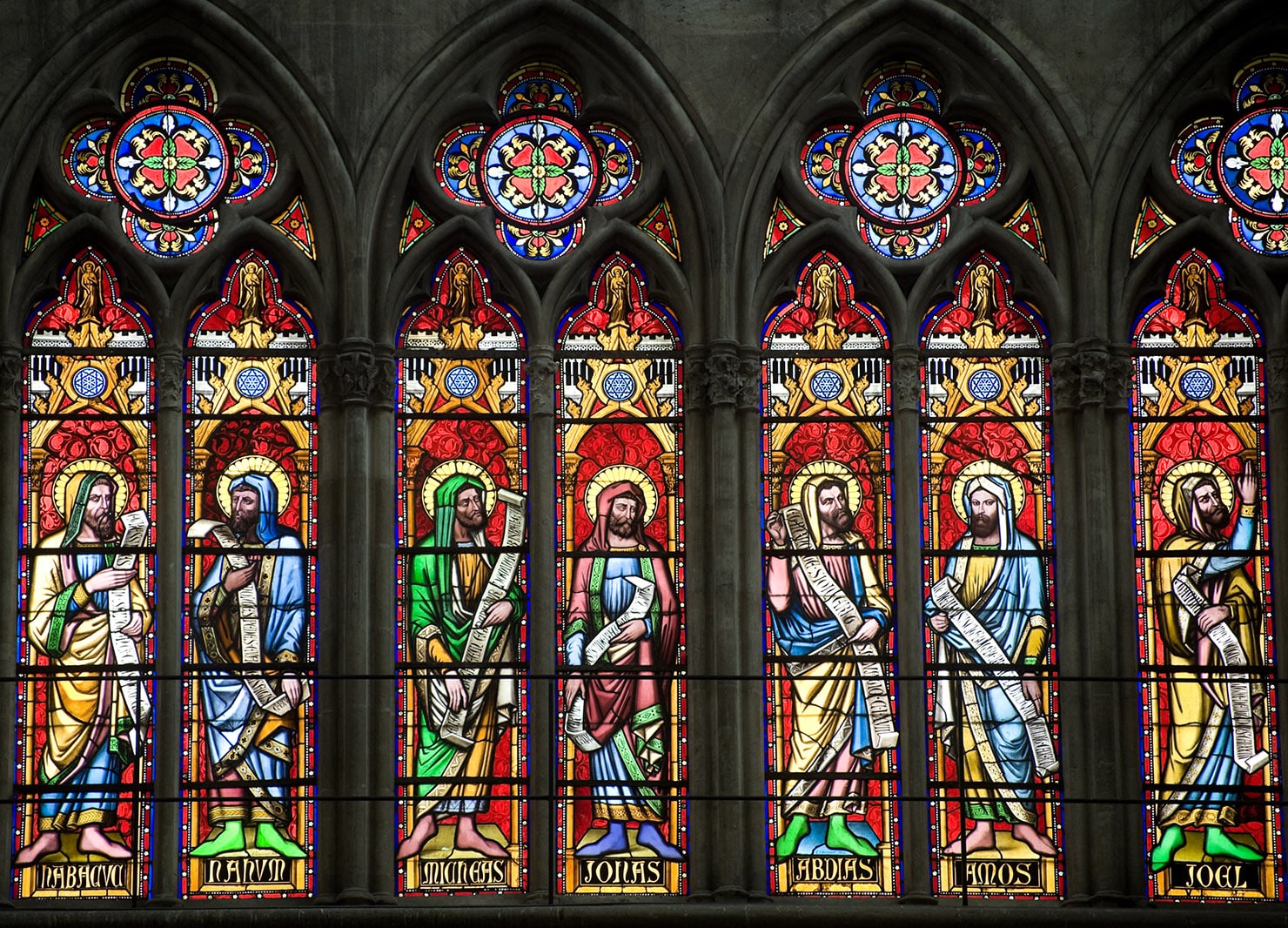

Converting to Catholicism

Before the end of their marriage, however, Rose and George surprised their peers and families by becoming Roman Catholic together. There are no journal entries or long letters explaining their decision, but George, presumably speaking for both of them, eloquently defended their decision in the newspapers of the day. The couple was instructed by Paulist priest Father Alfred Young in Manhattan and were received into the Catholic Church on March 19, 1891, at the Church of St. Paul the Apostle. Two days later, Archbishop Michael A. Corrigan of New York confirmed the couple and they embarked on their Catholic life with a zeal and enthusiasm that is remarkable. The two became involved in a Catholic summer school, public speaking engagements and the shared work of writing a biography of the Georgetown Visitation convent. They both clearly embraced their Catholic faith, and we see in Rose’s journals and letters an openness to all the Catholic devotions that were popular in the day, an effort to learn and live the liturgical calendar of the Church and a deep love for the sacramental life. She also earnestly and frequently expressed the desire to serve. One brief but telling journal entry reads, “Asked at the Memorare that my life might be made a willing sacrifice.” She had a growing preoccupation with offering her life to God and neighbor. Her newfound faith as well as the culture and society around her — full of new settlement houses, charitable organizations and concern for immigrants — undoubtedly influenced her thoughts. In the book on the Georgetown Visitation convent and in other writings, we also see her esteem for women and men consecrated entirely to God. There is no indication from her own writings or those of others, however, that this esteem for religious and priests made her consider leaving her marriage. Rather, we see in the newly converted Rose a desire for her life, in whatever form she lived it, to be entirely at the service of God.

Sadly, by 1895, the tensions and George’s struggles with intemperance had become too much. Rose sought and was granted permission from the bishop for a separation. They never divorced but lived separately from then on. She makes it clear during the process that if the bishop thought it best for her to stay with her husband, she would stay. However, she admits to not feeling safe and expresses concern for George. She felt that it would not be in the best interest of his soul for them to continue to be together. Her grief was real, but the decision proved to be final. In the months that followed, she went on retreat and spent time with Julian and his family. By the summer of 1896, we see her taking steps into what would become the best-known and most all-consuming era of her life — nursing the sick poor, specifically those with incurable cancer.

Becoming Mother Mary Alphonsa

After George died in 1898, Rose established St. Rose’s Free Home for Incurable Cancer, in honor of St. Rose of Lima, in New York. Two years later, in 1900, she obtained approval to found her order, known today as the Dominican Sisters of Hawthorne, Congregation of St. Rose of Lima.

The chronology and historical narrative of the beginning of Rose’s new life’s work have been described beautifully in many articles and books, especially since the recent declaration from the Vatican that she is now venerable. The facts themselves are an amazing story, but here I want to let Mother Alphonsa speak for herself. For several years, she wrote a publication called “Christ’s Poor,” which shared with the public what she was doing and why she was doing it. Her faithfulness, dedication and love for Christ and the poor come through beautifully from her own pen. In an 1897 newspaper appeal to raise public awareness of her endeavors, she clearly described her aims:

I am trying to serve the poor as a servant. I wish to serve the cancerous poor because they are avoided more than any other class of sufferers; and I wish to go to them as a poor creature myself, through powerful to help through the open-handed gifts of public kindness, because it is by humility and sacrifice alone that we become worthy to feel the holy spirit of pity, and to carry into the disordered of destitute sickness the cheerful love we have gathered from the Heavenly Kingdom for distribution.

Serving the sick poor

In “Christ’s Poor,” in 1902, she reflected on her first experiences of the work and the realities of those early days of service. She frequently exhorted people to do what they could, to not be afraid to serve the sick poor:

When I first visited the sick I fancied that a trial of my skill and ability would lead to my prompt dismissal from the field by my poor friends. Now I see that I can be of such profound help, that I do not know what form of dismissal would get rid of me. But the sick do not by any means discourage me from coming. Every day is made beautiful by gratitude and welcome so genuine and strong with true life that I seem to be brushed aside by One who says: “I am here!” It is a privilege, is it not, to be near such vivid hope and love?

At times, she was more direct, addressing the question of why more people did not serve their less appealing neighbors or why they ignored the plight of the sick poor. She never minced words when she expressed her lack of patience for those who refused to help the sick. Having overcome fear, uncertainty and revulsion herself, she felt that others could and should try to do the same — and thus reap the same divine benefits that she experienced through meeting and serving Christ in the poor.

She put it simply: “We must love them (the sick poor). The saints kissed the feet of the poor. They did not seem to do so, only; they did it.”

A focus on Our Lady and the Eucharist

Two of the key elements of her fledgling community, which are still foundational today, were a love for Our Lady and the centrality of the Eucharist. She saw the sisters, this little band of women consecrated to God in service of the sick poor, as the women at the foot of the cross. She shares what this meant to her — to stay by Mary — in an article of hers published posthumously:

Children of Mary! Do they sometimes elect to stand by the Mother at the foot of the Cross? Not driven there by circumstances, but eagerly turning with the warm glow of the heart which comes from the holy impulse, the first real recognition of the great loveliness of Christ. Mary, the Mother, is there; she has crucified herself; she is happier there than she could be in the splendors of the city; her life is happiest near Jesus … and after His Death, she will be where the suffering and spiritual needs of human beings would have brought Him. … We know that Mary visits every abode of sorrow and suffering, and shall we fear to accompany the Immaculate Queen of Heaven when she invites us, by that warm glow of inspiration, of which the Child of Mary knows at least a faint touch, if not a rich abundance.

From her early days as a Catholic, she had a deep love for the Eucharist. She knew that this small community and the apostolate could not survive without our Eucharistic Lord at the center. This sentiment is clear in one letter she wrote to Alice Huber (Sister Mary Rose by this time):

This is a wonderful day. Our Blessed Lord has for the first time granted to this community the greatest of blessings (all-day adoration on First Friday) to its hours, to its visible offerings, and the greatest dignity to its outward observance. As I knelt during the first adoration, I could not but feel the difference to our whole being as a work, a group of enchained laborers, now that this glorious privilege (of adoration) has been given to us. You must come, and let successively your women come, on First Fridays to this chapel, or else manage to have the privilege at St. Rose’s Home. There is no describing the difference it makes.

A life of service

From the time she took up her life of service, Rose — or Sister Mary Alphonsa, after they were allowed to publicly profess vows as Dominican sisters on December 8, 1900 — never looked back and poured all her energy into both the community and making the lives of the patients cheerful and filled with the peace of Christ. It is unlikely she ever hoped to have her cause for canonization open, but her goal was heaven. She said clearly, “The whole aim of the community is to fit its members for the Beatific vision.” And she believed that, by serving God faithfully, we could all become saints. She wrote very beautifully:

Shall we try to find a better course for the ennobling of our souls than that laid out by Christ? … There can be no fervor without sacrifice; and the greater the sacrifice the greater the fervor. Since this heat is required of us, before we can serve God, the sacrifice is imperative; and a holocaust of all that we can sacrifice, because the Master we serve deserves great offerings; He shall have the greatest fervor and the work possible for us to offer Him.

Consecration means perseverance. The ‘ships are burned.’ Look back through history, and if you look into the historic literature of the Church, you will see what it means for a people to be consecrated to God. He asks us to be humble and meek; to remember that we are dust; and as we prostrate ourselves to offer Him all that we are, we find the sick poor at our side. …

After 30 years of service to the suffering Christ in the cancerous poor, Mother Mary Alphonsa died unexpectedly but peacefully on July 9, 1926 — the 84th anniversary of her parents’ wedding. The date, more than simply being poetic, seems to reflect that in her life of service, she found and surpassed what her parents had. As a spouse of Christ, she found the love that fed her heart, her mind and her soul, and brought her to a higher life than any human love alone could have — a life of heroic love.