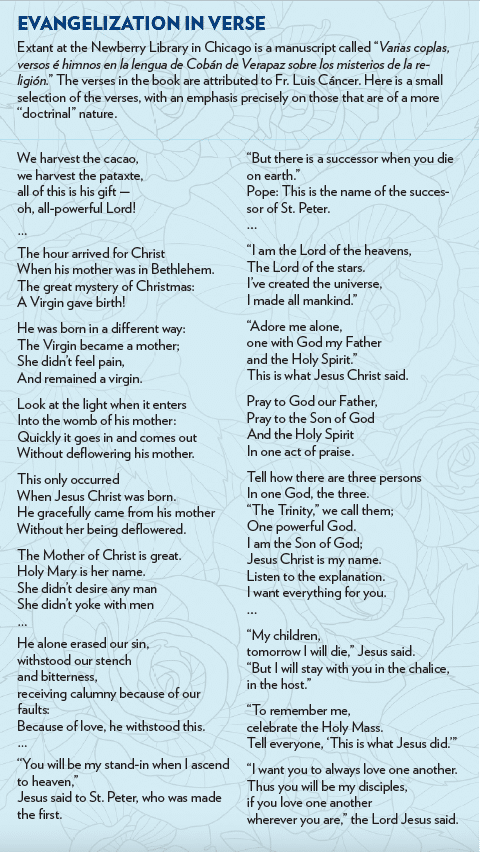

“He willed to die, no one obligated him; it wasn’t out of obligation. Rather, he consented.”

This verse was composed in the mid-1500s in a Mayan language spoken by one of the peoples of present-day Guatemala.

It was one of hundreds of such verses written and sung in order to teach the indigenous Central Americans about the Christian faith.

Sharing the Gospel through song was part of the brilliant and successful evangelization plan of Dominican friars from Spain, who were convinced of the dignity of the indigenous populations and had come to the New World captivated by a zeal to share the Good News of Christ with them (see sidebar below).

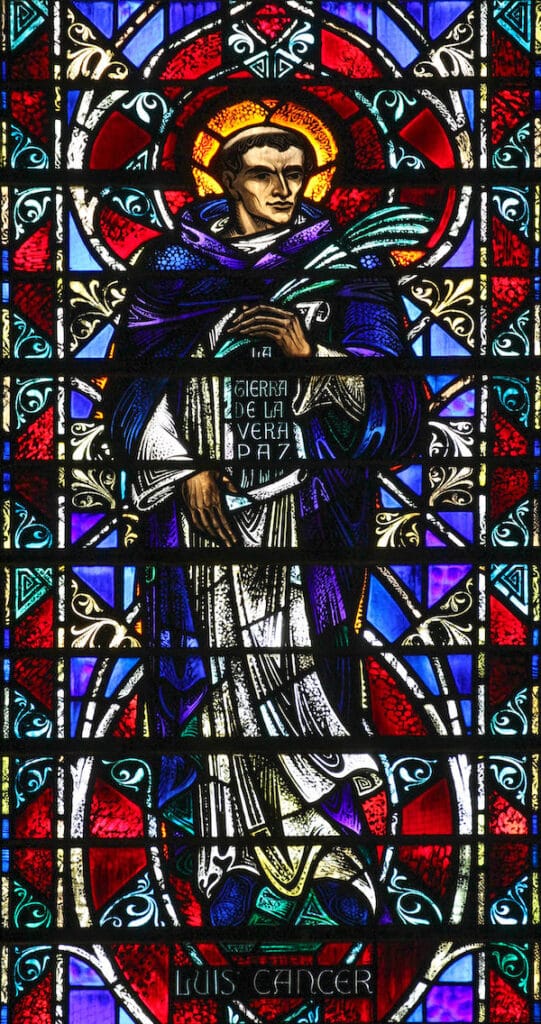

It was long thought that this verse, reflecting on Jesus’ assent to his passion and death, was composed by the priest considered the first martyr of Florida, Father Luis Cáncer, OP.

While there is now some historical question about whether it was Father Cáncer himself who wrote it, or a confrere who came just a few years later, what can be said about the verse is that it describes Father Cáncer’s martyrdom nearly as well as it describes Christ’s.

If Father Cáncer didn’t compose this one, he composed many like it.

Consumed by zeal

Luis de Cáncer, also known as Luis de Cáncer de Barbastro, was born sometime around the year 1490 — the name “Cáncer,” like the constellation and horoscope, is rooted in the Latin word for “crab.” Barbastro, Spain, where he was probably from, is not too far from today’s border with France. Huesca, Spain, just a few miles west, had a Dominican priory that had been founded in 1254. It’s likely that young Cáncer followed his priestly vocation there. He was quickly recognized as having a superior intellect, well-suited to an academic Dominican future.

But Father Cáncer had another consuming desire.

The young Dominican grew up amidst the electrifying stories of the New World, discovered almost at the same time as his birth. So before he had turned 30 years old, he convinced his superiors to put his gifts at the service of the evangelization of the new Spanish colonies.

In October of 1518 (or maybe 1514), he set sail to join the new Province of the Holy Cross on the island that is today formed by Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Some three years later, in 1521, he was off to neighboring San Juan, Puerto Rico, to become the first prior of a new friary there.

He served as prior for six years and then continued the ministry in Puerto Rico until 1542. About those two-plus decades in Puerto Rico, little is recorded. But we can imagine that, during those 20 years, the young priest matured greatly in his faith and in his love for the souls who were entrusted to him. He also had ample time to experience and perfect the real, daily work of evangelization, finding ways to effectively share Christ with those who had never before heard the name.

In 1542, Father Cáncer took on a new mission, this time in the “Land of War” — the name itself indicated what Father Cáncer would face there. The Mayan tribes of the area not only fought among themselves, but also, understandably, against the new tribes that had arrived from Europe.

But various Dominicans were making headway and Father Cáncer joined them. He was known to have a great facility with languages and, little by little, acquired the local tongues, including Quiché and Q’eqchi’.

Aware of the importance the indigenous gave to music, Father Cáncer prioritized song as the channel through which to share Christ.

From this time, and the incredible success Father Cáncer found there, we have hundreds of verses, some of which are shared here.

On to Florida

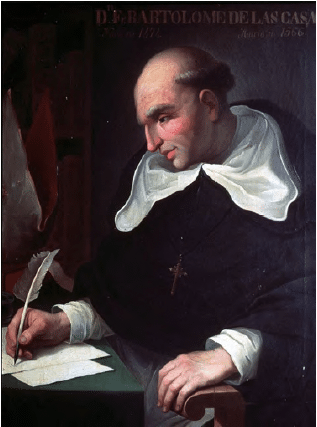

In March of 1547, Father Cáncer, along with his bishop and friend, Bartolomé de Las Casas, and other friars, headed to Spain to seek approval and financial support for a new mission to Florida. The so-called Council of the Indies, responsible for making decisions for the Spanish Crown, was reluctant because previous missions to Florida had not been what they considered a success. In fact, the indigenous Floridians had suffered greatly at the hands of the Spanish.

“Luis Cáncer was a fierce protector of the rights of the native peoples…and the pacifist approach to evangelization,” explained a vice-postulator of his beatification cause, Father Len Plazewski, for this piece.

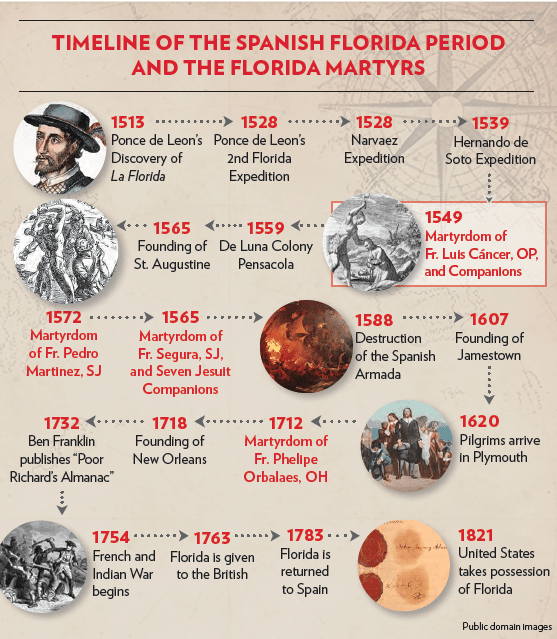

Over the span of some 10 years, the peoples of Florida had suffered greatly at the hands of the Europeans, under the directorship of Panfilo de Narváez and Hernando de Soto, in 1528 and 1539.

“Narváez in Cuba massacred thousands of women and children. This is the same guy who comes to Florida — a terrible individual,” noted Father Plazewski. “De Soto was not as bad as Narváez, but still a conquistador, looking for gold, etc….so the natives’ experience of the Spaniards was not very good.”

Before the Spanish authorities, Father Cáncer insisted that his mission would not be a military venture. He wanted to go to Florida to share Christ. Father Cáncer’s accomplishments in Guatemala were convincing and, by mid-December of that year, the Florida plan was approved and sponsored.

It took more than another year, however, to get it underway. And even with that time, Father Cáncer was not able to recruit any fellow Dominicans from the provinces in Spain. On March 9, 1549, Father Cáncer left from Seville, Spain, for Mexico, with supplies and gifts for the native peoples.

Sharing Christ

Once back in the New World, he was able to form a team with four men from the Mexican province to accompany him to Florida: Father Gregorio de Beteta (who previously volunteered), Father Juan Garcia, Father Diego de Tolosa and a brother, Esteban de Fuentes.

They would be accompanied by sailors, not soldiers, as Father Cáncer had convinced the Crown. They also took with them a native woman who would act as an interpreter, Magdalena.

The account of the next four weeks is told to us by Father Cáncer himself. The details are recorded in a diary that still exists in the General Archive of the Indies in Seville, Spain, today.

“You see the handwriting changes from Father Cáncer’s last entry, and Father Gregorio finishes the story,” Father Plazewski commented.

The four weeks that the sailors and Dominicans spent on the ship and the Florida coast were characterized by fear on both sides. Small landing parties were initially shot at. Some time later, with another attempt consisting of the pilot, several sailors, Father Cáncer, Father Tolosa, Brother Fuentes and the Indian interpreter, Magdalena, there was friendly interaction with some 15 to 20 natives. Father Cáncer and the others gave the natives gifts of goodwill. They even knelt together and prayed litanies, even if certainly the Floridians had little understanding of what they were doing.

After that seemingly successful interaction, Father Cáncer agreed that Father Tolosa and Brother Fuentes would go on by land, with the interpreter. But when Father Cáncer returned from the ship with more gifts, the three of them were nowhere to be found. The next day, the same.

Father Cáncer concluded that they had been captured and the remaining group decided to sail a bit south. It took them more than two weeks to find the entrance to modern-day Tampa Bay.

Corpus Christi on land

Father Plazewski notes:

“We can be certain that Cáncer and the other two priests celebrated Mass daily aboard ship and continued to pray for their associates and for the people they soon hoped to encounter. By this time they were short of drinking water, and they had a hard time finding more. On June 20, the feast of Corpus Christi, Father Cáncer recorded that he and Father Juan Garcia went ashore and found a safe place to celebrate Mass, which they did.

The priests and sailors continued to make excursions to land. At one point, they interacted with a large group of the native tribe, again offering gifts. In the midst of one encounter, they recognized Magdalena, but their Dominican confreres were not there. She claimed that they were at the chief’s house.

While Father Cáncer wasn’t sure he would be allowed to leave this group, he was, and returned to the ship. To his surprise, there he found a Spaniard, one of the members of De Soto’s expedition, who had been captured and in the New World these past 10 years. Hearing of the arrival of his countrymen, he had escaped, stolen a canoe and managed to make it to the ship. The Spaniard, named Juan Muñoz, assured Father Cáncer that his confreres were, in fact, dead. Father Tolosa and Brother Fuentes were thus the first of the group to be martyred.

We can imagine the situation on board at this point. In addition to the certainty that their lives were in danger, a number of the sailors were also sick with fevers, their rotted food had been thrown overboard, and they were not consistently finding fresh water.

Another motive to stay

Despite this, Father Cáncer didn’t want to leave. In addition to the zeal that had brought him to the New World so long ago, and now his loyalty to his deceased brothers, another motive weighed on him: He was worried about how Spain would treat this population if his peaceful mission failed.

In his diary, he recounts:

“And I thought no less each time I considered the greatness of this endeavor, but that it would be with blood, as was done by the apostles, that we would plant and establish here the faith and law of he who suffered and died himself in order to give it and preach it to us.”

Then he writes:

“[I]f Our Lord was not served now, time would still be made for it, but rather that to turn back with such news, in the opinion and statement of almost everyone, they would conclude (and badly concluded) that all these pagans were worthy of death, and deserved to have war made upon them, and their lands taken.”

In other words, Father Cáncer believed that he had to risk his life to protect the lives of the native peoples from subsequent military action on the part of the Spanish empire.

“One of his main fears is that if this mission fails, as previous expeditions had failed, he’s worried that the Spanish will come in heavy handed. He wanted to succeed so that the native peoples wouldn’t suffer from the Spanish military model,” Father Plazewski explained.

Another of Father Cáncer’s verses comes to mind:

“But the Lord died

To save us from suffering

So that we would not burn

In the infernal fire

And we would rise to Heaven”

Hope against hope

And, unbelievably, Father Cáncer still had not given up hope of spreading the Gospel. If he ventured out alone, as he had done in Guatemala, could an unarmed, gift-bearing friar yet convince them?

And if not, “if it happens, it’s not their fault.” In other words, if they kill him, it is because they are acting in their own defense, having seen for themselves what the Spanish could do.

Come what may

The next day was June 24, the feast of St. John the Baptist, one of the first to give his life for Christ. Father Cáncer took that day to prepare his solo return to land, writing letters, and organizing the gifts. June 25 brought rain, and the priest wasn’t able to make land. On June 26, the skies had cleared a bit but most of the soldiers refused to go to shore. Fathers Garcia and de Beteta agreed to take Father Cáncer to land, but it was agreed that they themselves would not stay.

So that day, along with their new translator, the escaped Muñoz, the three friars headed to land, with whichever sailors they managed to cajole or convince to row. Upon arriving, they encountered and called out to a group of the Native people, who were hiding in the trees. From the boat, the Spanish could see that the Natives were armed with clubs, spears, and bows and arrows.

At this point, Father Gregoria tried to convince Father Cáncer to abandon the plan, but, as Father Plazewski recounted, “Throwing caution to the wind and for the sake of proclaiming the Gospel, Cáncer jumped overboard and swam ashore. … As he slowly walked closer to the wooded area, Beteta speculated that Cáncer now realized the impending danger as Cáncer fell to his knees on the sand and waited in a moment of silent prayer.

“Instead of trying to make it back to the boat, Father Cáncer then stood up and slowly walked towards the group of Indians by the small forest. At the edge of the forest, an Indian came forward and grabbed him by the arm. Then the other Indians approached. One of them violently pulled away the hat Cáncer was wearing and another proceeded to hit him in the head with a wooden club. A group gathered around him and continued clubbing him until he died. After they had beaten Cáncer to death, an even larger number came out of the woods and began to fire a volley of arrows at the friars in the landing boat. As the boat retreated out of range from the arrows, the Indians then pulled out the habits of the other slain missionaries — perhaps as battle trophies or a warning against any future attempted Spanish incursions in their land.”

While Father Beteta at this point wanted to continue the mission in another part of Florida, the sailors simply refused. They took another day to find and collect water, and the ship left Tampa Bay on June 28, 1549, headed to Havana. Because of changing winds, it ended up in San Juan de Ulua, Mexico, making land on July 19, 1549.

The vice-postulator reflects that the news of the martyrdom of Father Cáncer and his companions quickly spread.

“It is important to understand that Luis Cáncer was not just some obscure missionary priest,” Father Plazewski explained. “He was extremely well known within the missionary community in the New World and those connected with such endeavors. His advocacy of Indian rights and his remarkable success in Guatemala contributed greatly to his notoriety. It is probably not an exaggeration to say that his untimely death sent shock waves through the Dominican Order and all those laboring for the Gospel among the Native peoples in the New World.”