In a 5-4 ruling upholding a Montana program to provide student scholarships for use at religious schools, the Supreme Court also in effect repudiated a 19th-century monument to anti-Catholic bigotry known as the Blaine Amendment.

The majority opinion in the case, announced Tuesday, was written by Chief Justice John Roberts, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh. Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan dissented.

Referring to the Montana constitution’s version of the Blaine Amendment, Roberts wrote, “The application of the no-aid provision discriminated against religious schools and the families whose children attend or hope to attend them in violation of the Free Exercise Clause of the federal Constitution.”

The Supreme Court ruling reversed a 2018 decision by the Montana Supreme Court based on the state constitution’s Blaine provision barring aid to any school “controlled in whole or in part by any church, sect or denomination.”

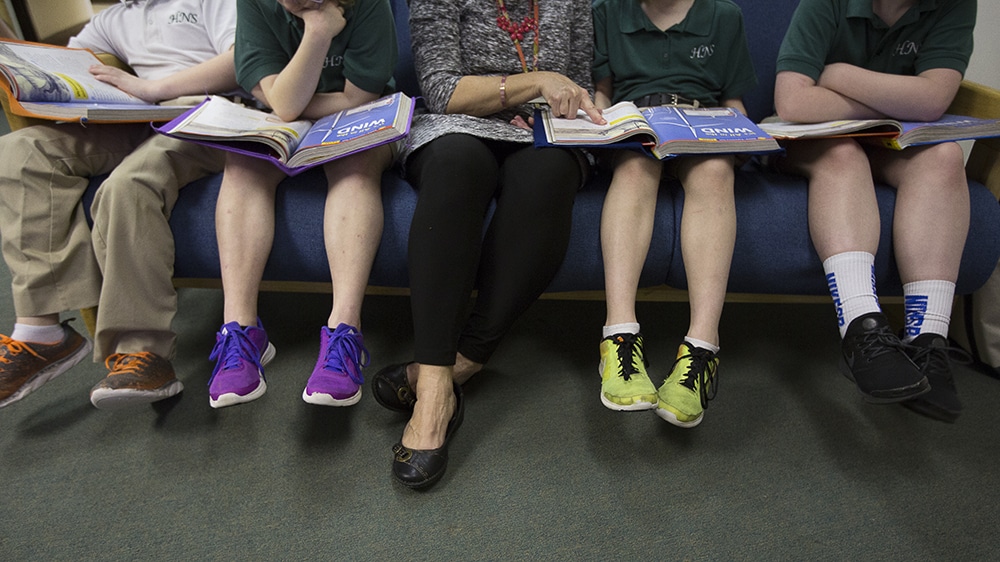

The Montana case (Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue) concerned a scholarship program enacted by the state legislature in 2015. The program provided a tax credit of up to $150 annually to individuals and businesses donating to private organizations established to receive the donations and disburse the money to families with children in nonpublic schools.

The only such organization set up to date awarded scholarships only to low-income families or families whose children have disabilities. Shortly after enactment of the program, the state revenue department adopted an administrative rule barring use of scholarships at religious schools. In doing so, it cited Montana’s Blaine Amendment.

That provision is named for U.S. Representative and Senator James Blaine, who in the 1870s argued for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution to bar use of public funds at religious schools. Coming at a time when immigration was rapidly increasing the Catholic population and Catholic parochial schools were growing in number, the proposal was widely seen as a reflection of Protestant anxieties about rising Catholic numbers and influence.

While Blaine never did become part of the federal Constitution, 37 states, with Montana among them, eventually adopted their own versions.

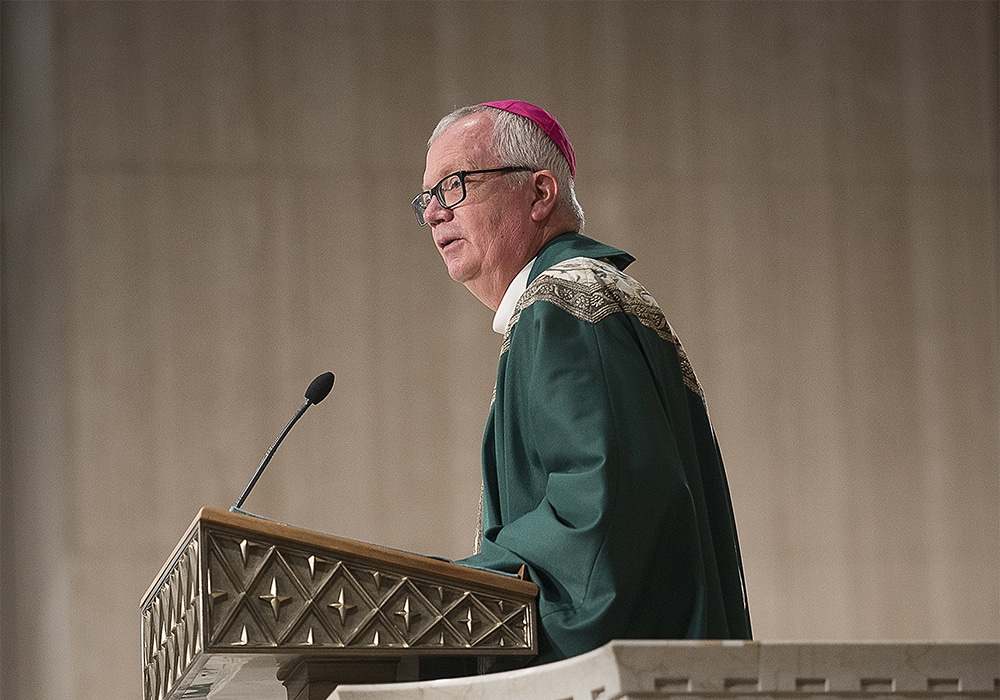

In a statement following the decision, Archbishop Thomas G. Wenski of Miami, chairman of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Committee for Religious Liberty, and Bishop Michael C. Barber of Oakland, California, chairman of the Committee on Catholic Education, said: “The Court has rightly ruled that the U.S. Constitution does not permit states to discriminate against religion. This decision means that religious persons and organizations can, like everyone else, participate in government programs that are open to all. This is good news, not only for people of faith, but for our country. A strong civil society needs the full participation of religious institutions. By ensuring the rights of faith-based organizations’ freedom to serve, the court is also promoting the common good.”

In striking down Montana’s Blaine Amendment, the bishops said, “The court has also dealt a blow to the odious legacy of anti-Catholicism in America. … [The amendments] were never meant to ensure government neutrality toward religion, but were expressions of hostility toward the Catholic Church. We are grateful that the Supreme Court has taken an important step that will help bring an end to this shameful legacy.”

The plaintiffs in the Montana case were three low-income mothers who said they counted on assistance from the scholarship program to send their children to a Christian school. The state Supreme Court’s decision dealt with the dispute by eliminating the state’s scholarship program entirely.

In his majority opinion, Roberts relied heavily on a 2017 Supreme Court decision (Trinity Lutheran Church v. Comer) that held that a Lutheran church in Missouri that operated a day school was entitled to receive funds from a state program for upgrading playgrounds as a safety measure.

In that decision, Roberts said, the Supreme Court held that “disqualifying otherwise eligible recipients from a public benefit ‘solely because of their religious character’ imposes a penalty” on religious free exercise. By that standard, he held, Montana’s denial of scholarships for use at a religious school did not pass muster.

Russell Shaw is a contributing editor for Our Sunday Visitor.