One student knew so much about the Civil War that when he incessantly talked about it, people got bored and walked away. Yet he added fascinating details in history class when the teacher recognized his gifts and encouraged him to share his knowledge.

Another socially awkward student named Jordan was a budding artist. Though not good at communicating, he had his classmates’ respect and attention when he drew things for them and when the teacher had him illustrate lessons on the white board.

“It was important for Jordan to be included in the class in meaningful and positive ways,” said Deacon Lawrence Sutton, PhD., who teaches pastoral counseling at St. Vincent Seminary in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. “That increased his self-esteem and benefited everyone else in the classroom who got to learn new topics from different points of view.”

Deacon Sutton, a licensed psychologist, is a permanent deacon in the Diocese of Pittsburgh. He melded his experience in psychology and teaching with his education in theology to write two books on the ministry of inclusion for individuals on the autism spectrum. The first was “Teaching Students with Autism in a Catholic Setting” (Loyola Press, $13.95) The second, released earlier this year, is “How to Welcome, Include and Catechize Children with Autism and Other Developmental Disorders: A Parish Based Approach” (Loyola Press, $12.95).

He also co-authored another book and numerous professional papers, and speaks nationally and abroad. He recently started a new blog to reach more people.

“It’s a way of conveying information about autism and what it is and what it isn’t,” he said. “I’m using this forum to share ideas, recent developments, trends and other information that may be useful to people who are on the autism spectrum or know someone who is.”

The diagnoses cover a wide range of symptoms and behaviors, from non-verbal severely affected individuals who need lifetime care, to high functioning individuals who may be brilliant but lacking in the executive functioning that’s important for developing social skills and understanding the neurotypical world. They often learn in different ways and tend to be well versed and focused on what interests them.

Soon after Deacon Sutton was ordained in 1999, he learned of two children who were denied First Communion because they were on the spectrum.

“I was very surprised and I became very upset,” he said.

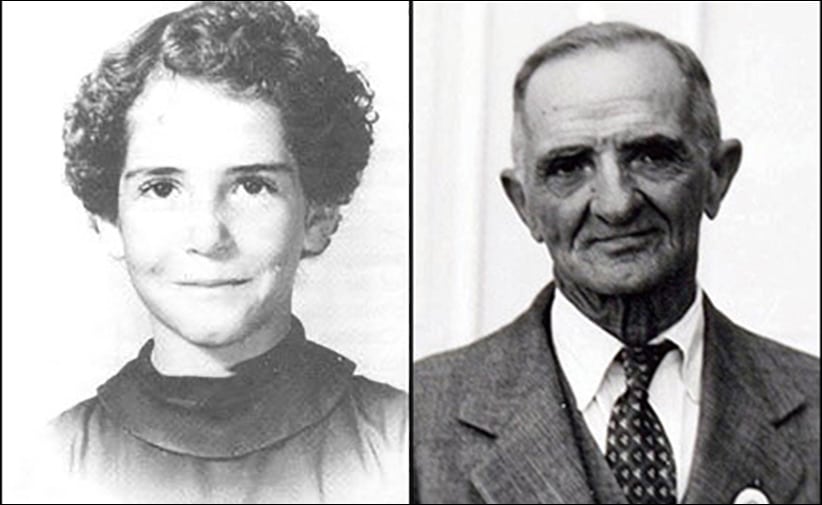

He turned to Grace Harding, director of the diocesan Ministry for Persons with Disabilities. Years ago she collaborated with Eunice Kennedy Shriver to pioneer the Rose Kennedy Curriculum in Pittsburgh. Shriver, Rose’s sister, was an advocate for persons with developmental disabilities and who founded what became the Special Olympics.

“Grace gave me a copy of the curriculum, told me good luck, goodbye and she retired,” Deacon Sutton said. “I did nothing for a year. Then maybe the combination of the Holy Spirit, my restlessness and my psychology background led me to form a different sacramental program with an understanding of how children with autism look at and understand things, and how a religious education should be taught to them.”

He developed a program that trained neurotypical teens as mentors and teachers to work one on one with individuals with autism and he supervised them as lead catechist. Parents attended as well and they saw, he noted, that teenagers without special education degrees could teach their child about God.

“When it came to receiving reconciliation and the Eucharist, the children were prepared,” he said. “They knew right from wrong and were ready. When one child received the sacrament of confirmation, everybody cried. His parents thought it wasn’t possible.”

Deacon Sutton took his programs and curriculum (“Adaptive Finding God”) on the road to Catholic schools and dioceses. He spoke at conferences and wrote professional papers and books grounded on the Catholic principle that every person has dignity and possesses gifts to be shared with the greater community. Educators can become agents of God’s grace in improving the lives of children with autism.

His work doesn’t focus only on children. He addresses what’s possible when a child on the spectrum becomes an adult, and how high functioning individuals can have successful lives and marriages.

For instance, the partner on the spectrum can learn what’s expected to have a good relationship, like how to anticipate the other’s needs that may not be apparent because of different perspectives.

“I teach in my seminary classes that the sacrament of marriage isn’t just for neurotypical people,” Deacon Sutton said. “When we talk about disability ministry, I say that if you don’t address disabilities within your church, you’re going to miss connection with a lot of people. So it’s important to recognize who’s out there.”

That also means recognizing those in vocation who are on the spectrum.

“I’ve found that God’s call to religious life isn’t just made to neurotypical individuals,” he said.

In response to that, Deacon Sutton is collaborating on another book, “Autism and Holy Orders” to recognize and support seminarians and priests with that diagnosis.

Between writing, teaching and speaking, he’s developing his blog to reach out with information and a platform for discussion.

“We have a responsibility to build that capacity to help others,” he said.

Although challenging, there are rewards.

“When I look at the happy child who has received the Eucharist and I look into their eyes,” he said, “I see the eyes of God.”

Maryann Gogniat Eidemiller writes from Pennsylvania.