The head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Major Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk, archbishop of the Major Archeparchy of Kyiv-Halych, “is a bridge between different eras: the communist persecution of the Church, its revival, and its response to various modern challenges, including the war,” writes Myroslav Marynovych in the forward to a new book by John Burger from Our Sunday Visitor.

Hailed an international hero by many, Archbishop Shevchuk is far from a household name for the average American. As we mark the first anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Our Sunday Visitor sat down with John Burger, whose expertise offers a thoroughly-researched portrayal of a lesser-known, but profoundly inspiring Christian leader.

Our Sunday Visitor: Who is Archbishop Shevchuk? How would you introduce him to an audience who may not have known him or paid much attention to Ukraine before the war?

John Burger: He is the head and father of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, which is the way the Church refers to him. Of the 23 Eastern Catholic churches that are in communion with Rome, the Ukrainian Catholic Church is the largest. His Beatitude is the archbishop of Kyiv, the way the pope is the bishop of Rome, so he’s got that jurisdiction. He oversees all the eparchies in Ukraine.

But he’s also the head and father of the worldwide diaspora of Ukrainian Catholics. For centuries now, the Ukrainian Catholic Church has planted its roots in North America, South America, Australia, now even South Africa … anywhere that Ukrainians go, the Church follows. He has a global presence and importance, and he really represents who Ukrainians are through his own personal story, even though he’s only 52.

| READ MORE |

|---|

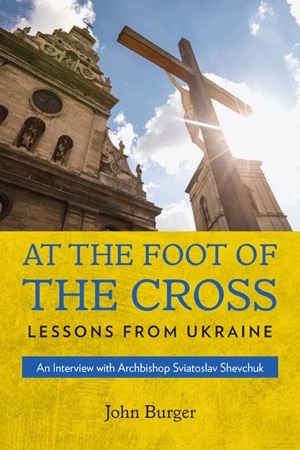

In the new book “At the Foot of the Cross: Lessons from Ukraine — An Interview with Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk” (OSV, $21.95), the head and father of the Ukrainian Catholic Church offers deep insights about the direction in which the world is going, including the struggle the Church once again faces, 30 years after the fall of the Soviet Union, in light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Order the book online at OSVCatholicBookstore.com. In the new book “At the Foot of the Cross: Lessons from Ukraine — An Interview with Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk” (OSV, $21.95), the head and father of the Ukrainian Catholic Church offers deep insights about the direction in which the world is going, including the struggle the Church once again faces, 30 years after the fall of the Soviet Union, in light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Order the book online at OSVCatholicBookstore.com. |

Our Sunday Visitor: Tell us more about that story, those details of his life that you think represent Ukrainians.

Burger: It seems so long ago right now, but it was only 30 or so years ago that the Soviet Union broke up. His Beatitude lived his first 20 years growing up in Soviet Ukraine. Because of that, he has first-hand experience being an underground Catholic, since their Church was illegal. Along with his family, he had to find ways to live the Faith. And not only that, but his own vocation to the priesthood also developed in that milieu. He had to study for the priesthood in an underground seminary.

Not only is it a dramatic story, but it has a lot of lessons for us. We Catholics in the United States, in the 20th century, sometimes think things should be this or that way, and that leads to a spirit of divisiveness. We can also take our faith for granted in many ways. But when we hear stories like Archbishop Shevchuk’s story, it takes us back to what is essential.

Our Sunday Visitor: You’ve traveled to Ukraine, and you’ve met multiple times with His Beatitude. What are some of the moments of the book that you think might surprise American readers?

Burger: Thinking back to the invasion, one year ago, it may have escaped many Americans’ notice that Archbishop Shevchuk was on a Russian hit list. Some people referred to it as “Putin’s hit list.” Apparently, Russia believed that they’d be able to decapitate the Ukrainian government within three days. But the Russians also knew that Ukrainians are fiercely proud of their country and there would be not only military resistance, but civil resistance. There would be people who would not cooperate with any Russian installed government in Kyiv, so they had to be silenced or exiled from the country or, I hate to say it, assassinated. U.S. or British intelligence had discovered this list, and His Beatitude’s name was on it. And yet he and most of his priests were determined to stay with their people.

Our Sunday Visitor: What is Archbishop Shevchuk like as a wartime leader? Under the current conditions, how is it that he continues to shepherd and inspire his people?

Burger: Early on, he made a point of issuing a daily video message. Because of the list of targets I mentioned earlier, he had to take shelter in an undisclosed location. He initially started the videos to make it known that he was still alive. He’s kept up with it, and each message follows a similar framework — thanking God and thanking the Ukrainian military that they were able to see the light of another day. He gives an update on the fighting and how the civilian population has been affected. And then he gives a little catechesis.

I think his optimism harkens back to his days when he was a seminary professor, when Ukraine was newly independent of the Soviet Union and his own Church was coming out of the underground. He knew that in order to rebuild society after such a long time under the Soviet regime, he had to inject a new way of thinking in Ukraine. He relied then, as now, on four pillars of Catholic social teaching: the dignity of the human person, subsidiarity, solidarity and the common good.

In addition to that, he makes trips around the country as much as his security permits it. He visits various parishes, speaking with his priests and his people. Certainly, he’s been in the west of Ukraine quite a bit because that’s a little bit more protected from the war at this point so far. He’s been in touch a lot with Pope Francis, both by phone and in person. He’s been to the Vatican a couple of times since the outbreak of the war. His Beatitude carries the grief and the concerns and the struggles of the people directly to the pope. I understand he’s been providing the pope with lists of prisoners of war hoping that Pope Francis can intervene in some way through diplomatic channels and arrange a prisoner exchange.

Our Sunday Visitor: What prompted you to write this book? At the time when you conducted your interviews with Archbishop Shevchuk, the situation in Ukraine was very different than it is today, one year after Russia’s invasion.

Burger: I was interested in the Eastern Churches to begin with. I’m a practicing Ukrainian Catholic. I’m not Ukrainian, but the Byzantine liturgy attracts me very much. And as a reporter in various publications, I’ve always tried to be mindful of the Eastern part of the Church as well as the Latin Catholic Church. So when I heard that His Beatitude was coming to the United States in 2018 to give the keynote address at the Knights of Columbus’ Supreme Convention, I requested an interview. One of his assistant priests who was traveling with him apparently liked the articles I then produced and said “look, there’s never been an English language biography of him.”

Our Sunday Visitor: What should American readers take away from Archbishop Shevchuk’s story?

Burger: For many people, it will be learning about a different part of their own church. Perhaps they will discover a new appreciation for the faith of people in the East. I hope too, that they will have a new appreciation for that history of being underground, when Catholics had to worship in secret, listening to broadcasts of the Divine Liturgy from Vatican Radio when it was illegal to go to Mass.

There’s a real possibility that something like that could happen again in Ukraine if Russia were to take over. Anytime Russia has controlled Ukraine there’s been a severe restriction of religious freedoms. Certainly the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, which is more in tune with the West, even seen as an agent of the West, an agent of the Vatican and agent of Western powers has been restricted. It’s a church that did not cooperate with the Kremlin during those years, (1946-89).

Faith is not to be taken for granted. We could lose our own freedoms quite easily. I think Americans have seen enough of such restrictions in their own lives that they can relate to His Beatitude’s story.