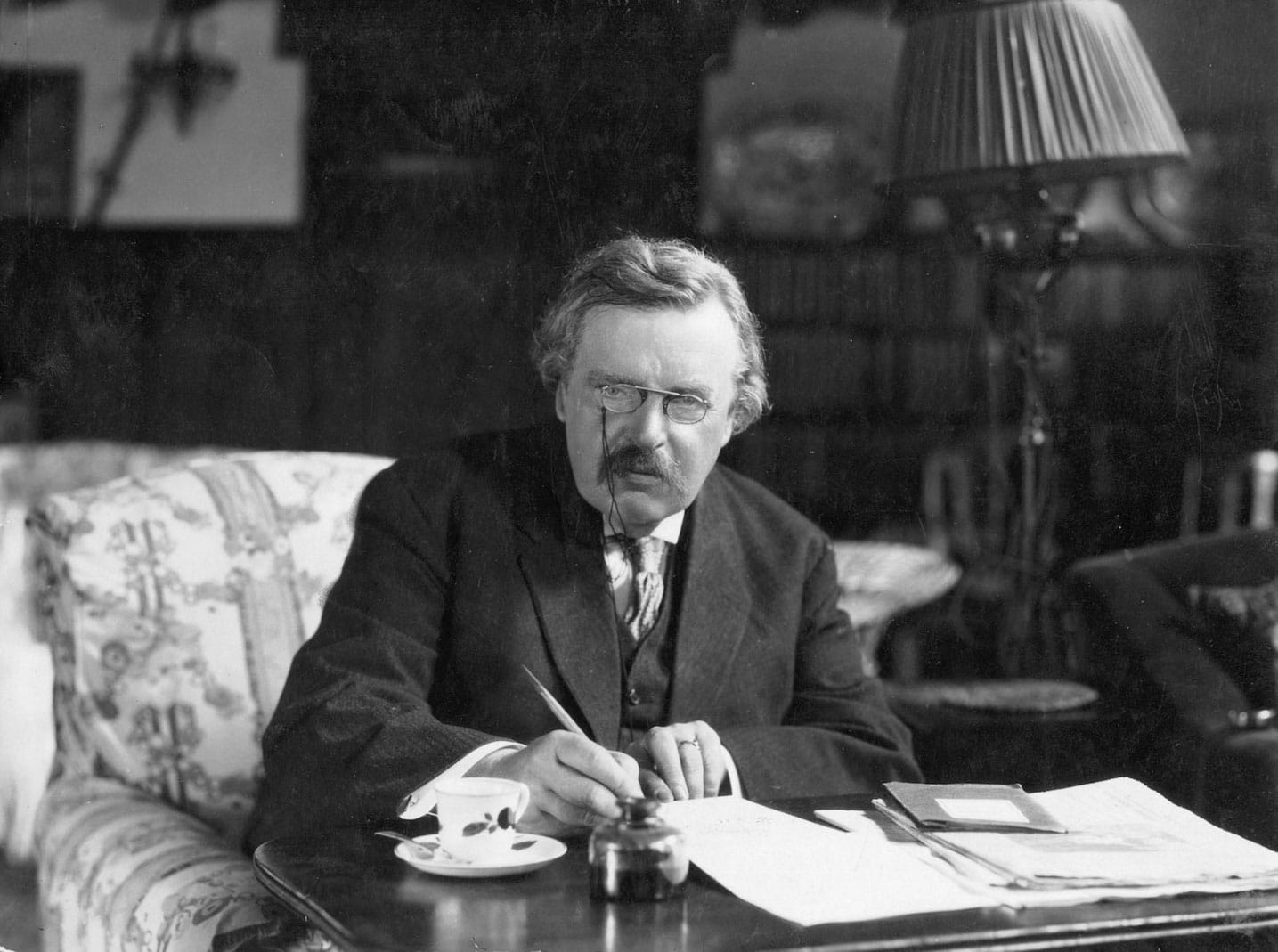

It’s a great line, but also one of the more dangerous among G.K. Chesterton‘s famous sayings. “If a thing’s worth doing,” he said, “it’s worth doing badly.” It gives some people an excuse and misdirects others.

Though as I say, it’s a great line. It rejects a pernicious modern idea of success, the idea that makes people say “I can’t do that very well, so I shouldn’t even try.” It rebukes the voice (internal or external) that says of something you want to do or feel called to do, “You’ll make a mess of it. Don’t even try. Leave it to the professionals.”

We hear people talk like that all the time. Gifted people won’t exercise their gifts because they feel they’ll never be good enough, judged by unrealistic and impractical standards.

I thought the line really dumb when I first read it, because I thought the key words are “doing badly,” and why should you encourage people to do anything badly? People produce enough bad work without encouragement.

I didn’t see that “worth” is the key word. Chesterton begins with reality, not what we do with it. That is, with affirmation, not judgment. One day I finally saw that he only meant that a thing worth doing is … worth doing.

The clever part was his contradicting, with that unexpected last word, a very common mistake that denies the worth of worthy things unless you do them up to someone’s standards. He helps us see how broad a range of performance “worth” could cover.

Ripe for misuse

The saying comes at the end of a regrettable chapter in his book “What’s Wrong With the World” titled “Folly and Female Education.” He argues that women don’t need to be educated like men because the world needs the “great amateur,” who “smatters” and “dabbles” in things.

He thinks women the great amateurs, who know a little about a lot, which they pass on to their children, while men know a lot about a little and thereby support their family. The chapter ends: “The elegant female, drooping her ringlets over her water-colors … was maintaining the prime truth of woman, the universal mother: that if a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.”

Outside the original context, it’s a liberating insight for people held back by the illusion that they must be good enough. But some people misuse it to excuse bad work and think they’re acting on Chesterton’s authority. It also stands for a lot of bad ideas of the same sort, invoked for the same reason, like “At least I’m doing something,” “God doesn’t care how good I am at this,” and “God looks on the heart.”

It can be taken to mean: If a thing’s worth doing, it doesn’t need to be done as well as I can do it; if a thing’s worth doing, it’s worth doing even though I have no gift for it and no reason to do it; if a thing’s worth doing, it’s worth doing even when I should be doing something else; even, if a thing’s worth doing, it’s worth slacking.

What are you called to do?

In my long experience as an editor working with Christian writers, writers have offered that line (or the others I mentioned) to justify giving me badly written articles, articles they knew were not good enough, and refusing to do the work needed to fix them. Some, let me be clear, actually said this out loud. While still expecting, and this baffles me, to be published.

People doing similar work to mine have complained about this, as well. Pastors have lamented the quality of work they get from some volunteers, who wouldn’t do such poor work for anyone else. But for the Church? Whatever.

Chesterton’s line gives some people an excuse for doing bad work, but it also pushes us to think more clearly about duty and calling. The question to ask isn’t whether a thing is generally worth doing, even badly, viewed without reference to specific human beings. The question is whether you’re called to do it, if it is one of the things you should be doing with your limited time and energy.

Sometimes, someone who can’t do something well should do it. But not everyone should do anything they feel like because if it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing badly.

A man is justified in writing wretched love poetry to his wife. He’s not justified in appointing himself a poet and spending his days writing his wretched poetry, with the rejection slips piling up, rather than making money to house and feed that wife and their children. (I have seen versions of this, and it’s sad.)

With that experience, I’d revise Chesterton’s saying: If a thing’s worth doing, it’s worth doing badly if you’re supposed to do it.