Among my favorite novels is Walker Percy’s Christian existential classic, “The Moviegoer,” winner of the 1962 National Book Award. The protagonist and narrator of the first-person novel, Binx Bolling, is on a self-described “search.” “What is the nature of the search?”, asks Binx. “Really it is very simple,” he explains:

“The search is what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life. This morning, for example, I felt as if I had come to myself on a strange island. And what does such a castaway do? Why, he pokes around the neighborhood and he doesn’t miss a trick.”

Put another way, the search is what takes Binx out of the everydayness of his own life on a quest for self-identity. The search is not an attempt at self-invention. Nor is it an exercise in narcissistic self-indulgence. Rather, it is Percy’s account of how we find meaning in our lives through a variety of resources and experiences, especially in relationships with other people.

Binx emerges from “everydayness” by observing signposts and signals that provide hints and clues about who he is. Binx finds himself in relief to things and other people, by his orientation to and relationship with others. Most importantly, he seeks to understand himself in relation to one specific person, through a climactic experience of self-giving. (You’ll have to read the novel to discover who that “other” is, and how both are affected through Binx’s search.)

Jon Fosse’s postmodernism with a purpose

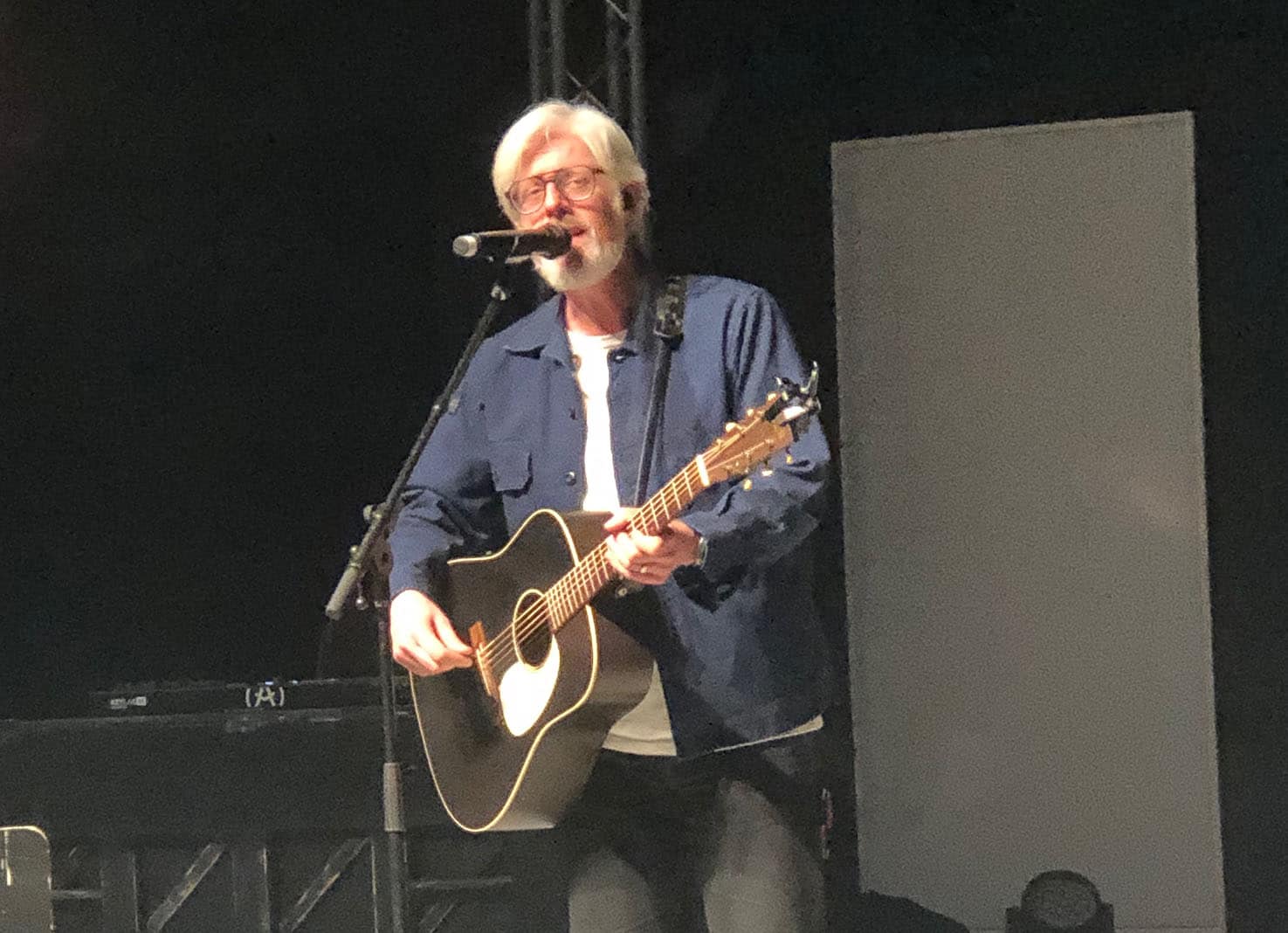

I often thought about Binx Bolling and “The Moviegoer” as I recently read the astonishing series of seven novels, “Septology,” by the brilliant Norwegian novelist, essayist, and playwright Jon Fosse. I have to confess to never having heard of Fosse before he was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in October 2023. The Nobel citation noted Fosse’s “innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable.” In the press conference announcing the award, Anders Olsson, chairman of the Nobel literature committee, noted “Fosse’s sensitive language, which probes the limits of words.”

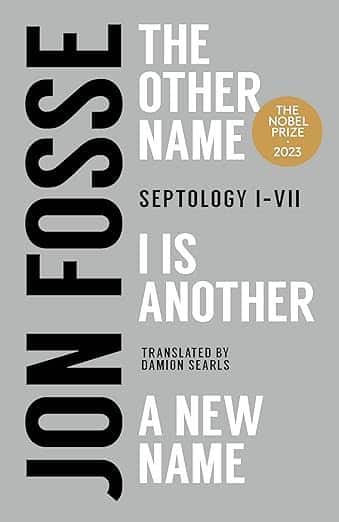

As noted above, “Septology” is a sequence of seven novels. But they are grouped in three volumes, the English translations of which give a clue about Fosse’s use of the names of his characters to probe the depths of self-identity and human relationships: “The Other Name” (novels 1 and 2), “I Is Another” (3 through 5), and “A New Name” (6 and 7). While Fosse falls squarely in the “postmodern” school of novelists, “Septology” is more accessible than such authors as Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon and Italo Calvino, for example. To be sure, they share techniques. But Fosse’s work seems to be less interested in demonstrating his cleverness and more in exploring the depths of human experience.

‘Septology’ probes the meaning of personhood

The main character and narrator of Fosse’s novels, the aging artist Asle, is remarkably similar to Percy’s Binx Bolling. Asle searches for meaning in the signs, images, and people that provide the context of his own self-awareness. I don’t know whether Fosse knows Percy’s work. But Binx and Asle are clear literary cousins. Like Percy, Fosse is a convert to Catholicism, as is Asle, who makes a modest living as a relatively successful painter. Catholic sacramental theology is at the center of Asle’s life. The prayers of the Rosary frame his first-person narration.

“Septology” probes not only the limits of words, but the very meaning of personal identity in the concrete “everydayness” of human experience, to borrow Percy’s word. In the process, he provokes his reader to think deeply about what it means to be a person, and how that meaning is developed in relation to others. Asle’s life is closely intertwined with another aging painter, also named Asle, whose life is strikingly similar to the narrator. Indeed, the blurring of the lives of the two Asles is at the heart of the genius of the novels. The reader is challenged to think about whether the two Asles are actually different people, or the same person with two different identities, formed around the contingencies of counterfactual suppositions.

Most importantly, in “Septology” Fosse accounts for the solicitude of God’s redemptive activity in the world. He does this by accounting for the narrator’s experience of grace, in contrast to those around him who have shunned a life of faith for fleeting experiences that cannot fulfill the longings of the restless heart. The Catholic reader will be especially interested in Fosse’s examination of such weighty matters as the nature of personhood, moral agency, suffering, death, the hiddenness of God and the sacramental nature of human experience. If, like me, Jon Fosse is a new name for you, I enthusiastically commend “Septology” as an introduction to this innovative writer, whose art is informed by Catholic faith and sacrament.