A popular quip — attributed to figures diverse as Victor Hugo, Edmund Burke and Winston Churchill — states: “If a man is not a socialist by the age of 25, he has no heart; if he continues to be a socialist after age 25, he has no head.” The saying actually seems to be a mangled paraphrase of a 19th-century French historian’s distillation of one of Burke’s insights on the French Revolution. In other words, it originally wasn’t about socialism at all. But it is not without reason that the saying has become popular in this form, as its meaning rings true for many in spite of its dubious provenance.

The saying also reminds us that words and phrases sometimes morph and develop through time. “Liberal,” for example, once meant proponents of free markets and small government; now it resonates with the opposite meaning. The term “socialist” similarly has a confused pedigree. And with increasing numbers of (especially young) Americans identifying in surveys as socialist, and the popularity on the rise of figures such as Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who publicly espouse “democratic socialism,” the task of understanding such terms has become urgently important for Catholics. After all, even some of our co-religionists say they espouse a kind of “Christian socialism,” which they argue to be commensurate with the Church’s teachings on economic justice.

What the present moment calls for is a hermeneutic, or interpretive lens, that takes into account the dual lessons borne by the above mis-quotation: the lesson that some are beguiled into forms of socialism for reasons of genuine compassion, and the lesson that terms such as socialism can become muddied over time. Especially in 2020, when self-proclaimed “anti-fascists” are marching the streets and committing acts of vandalism against “the patriarchy,” and even the Black Lives Matter Global Foundation’s founders state that they are “trained Marxists,” how can Catholics form their conscience in order to engage in such conversations with truth and charity?

To some readers, the answer seems obvious. It may be you were raised amid the Cold War and remember the air-raid drills, the ever-looming threat of the Soviets. Or it may be that you are well-read in the Church’s social doctrine and are aware of the papal magisterium’s consistent and firm condemnation of socialism, most neatly encapsulated by Pope Pius XI in 1931: “Religious socialism, Christian socialism, are contradictory terms; no one can be at the same time a good Catholic and a true socialist” (Quadragesimo Anno, No. 120). Or it may be simply for you a knowledge of the gruesome history of the 20th century: the fact that socialism in the space of a few decades amassed a body count dwarfing that of any ideology or movement in all previous centuries combined, and that it would still be the deadliest social institution in history if only it had not been surpassed by abortion at the end of the millenium.

But the answer is not quite as obvious if we recall our hermeneutic from above. We should be charitable in interpreting others’ actions and deeds, remembering that even misguided actions sometimes have laudable motives and that words sometimes can obscure the intended meaning of the speaker.

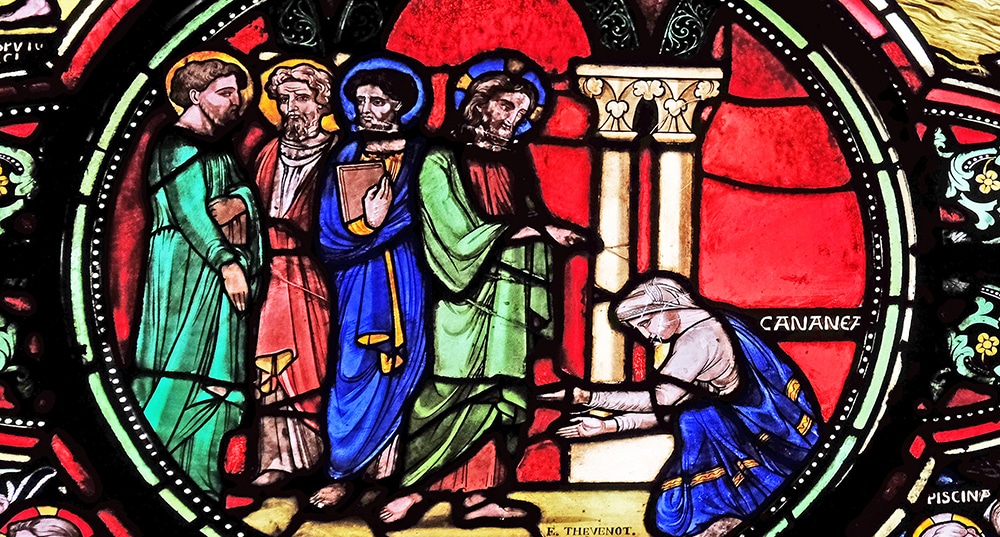

First, we must always have in mind that compassion and care for the poor are non-negotiable and essential facets of the Christian life. Affective maturity for the Christian necessitates taking up and heeding the Lord’s call to love both one’s neighbors and even one’s enemies (who, as G.K. Chesterton once observed, are very often the same person). After all, the Gospels warn unequivocally what fate awaits those who fail to perceive Christ in the hungry to feed him, in the thirsty to slake him, or in the naked to clothe him: “the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels” (Mt 25:41). We must recognize the truly laudable and virtuous intent in those who work for economic justice and racial equity, and seek to unite ourselves to these causes whenever and however we can, provided we can do so without compromising on other essential commitments to truth. Perhaps our young neighbors’ heads might not be in the “right place,” but very often their hearts are.

Second, we should remember to seek the substantial meaning behind one’s words, giving benefit of the doubt wherever we can to what a speaker intends. St. Paul admonished Timothy to tell his community to “stop disputing about words” (2 Tm 2:14) — and that was long before Twitter! Many people who today assert they are socialist may hardly even know what they themselves mean by it. We should engage them, gently letting them know the magisterium’s guidance on the matter and proceed to debate matters of economic policy with serene charity. We should bear in mind that these individuals probably are adopting the moniker “socialist” because they want to feed the poor and not because they want to ship off ideological opponents to gulags. And we should assure them that we share their passion for uplifting the poor and downtrodden and that the Church has alternatives to Marx when it comes to that.

In such a way, we can begin to make sense of the confusing political times in which we find ourselves, and hopefully find a way to confront the age and our neighbors with full use of both our hearts and our heads.

Joe Grabowski is executive director of the International Organization for the Family. He writes from Pennsylvania.