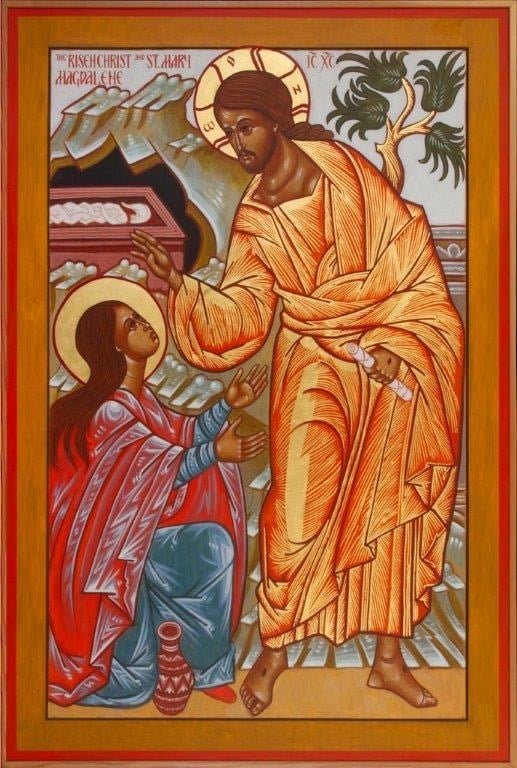

“An icon isn’t really an icon without a viewer,” Charles Rohrbacher said.

“Icons are looking out at us, and we complete the circuit, as it were.”

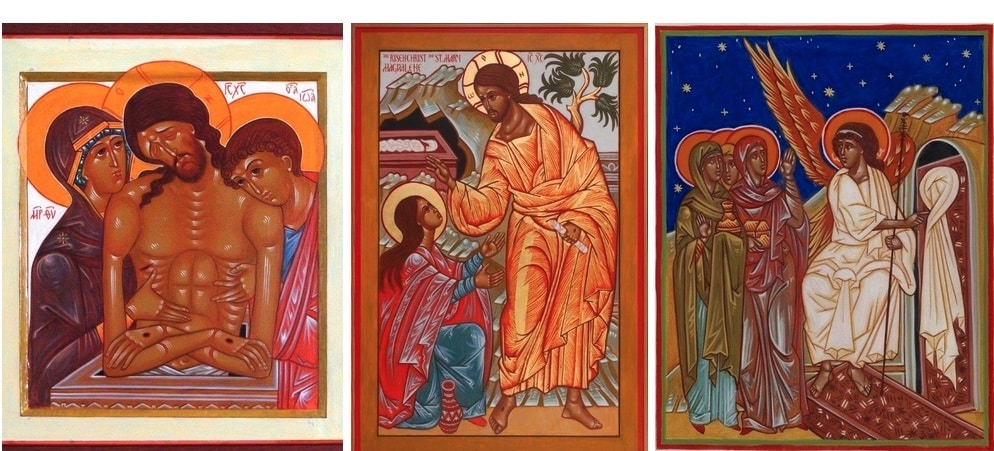

From his small, crowded workshop in Juneau, Alaska, the 68-year-old deacon and iconographer sends his icons out to be present for any viewer who’s willing to see and to be seen, whether in churches, in private homes or in books.

He painted his first icon for his grandmother when he was 8 years old. She kept the crude watercolor of Jesus by her bedside and prayed her Rosary before it every night.

But although Deacon Rohrbacher kept turning out art from that day forward, and went on to study art history and graphic design, it was not until the 1980s that he rediscovered iconography and began to understand how powerful these sacred pictures, with their ancient tradition of preaching the Gospel through images, could be.

He made friends with Dmitry Shkolnik, a Russian iconographer who brought him to the Easter Vigil at an Eastern church.

“The whole interior was painted in fresco from top to bottom, and I thought I had gone to heaven. I had this realization: This is what I’ve been looking for. This is what I’m called to,” Deacon Rohrbacher said.

It wasn’t just the aesthetic appeal. Around the same time, Deacon Rohrbacher was at a gathering at a Salvadoran church in San Francisco, where Catholics were grieving the martyrdom of Archbishop Oscar Romero. Someone had drawn his picture on a piece of white cardboard, and the people surrounded the image with flowers and candles as they prayed.

| More from Deacon Rohrbacher |

|---|

|

He recently finished a decadelong, an illuminated manuscript of The Benedicite, which is crowded with animals and angels. His work and commission information can be found at charlesrohrbachericons.com. |

“Knowing next to nothing of the theology of the icon, it occurred to me that, when everyone said ‘¡Presente!’ when his name was read [a Latin American invocation signifying that the dead are still with us], these evil people have murdered him, but he is present among them. His image signified his invisible presence, along with Christ and Mary,” he said.

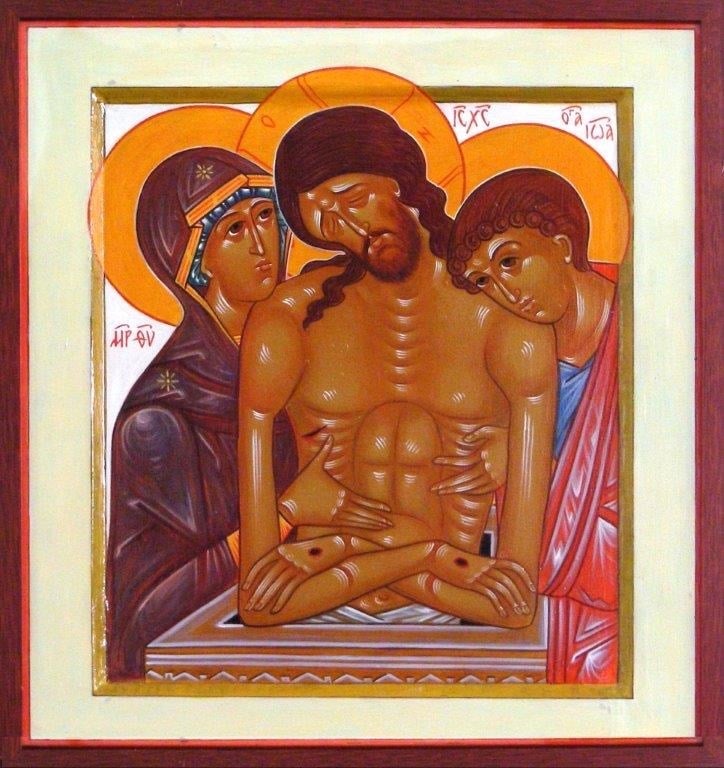

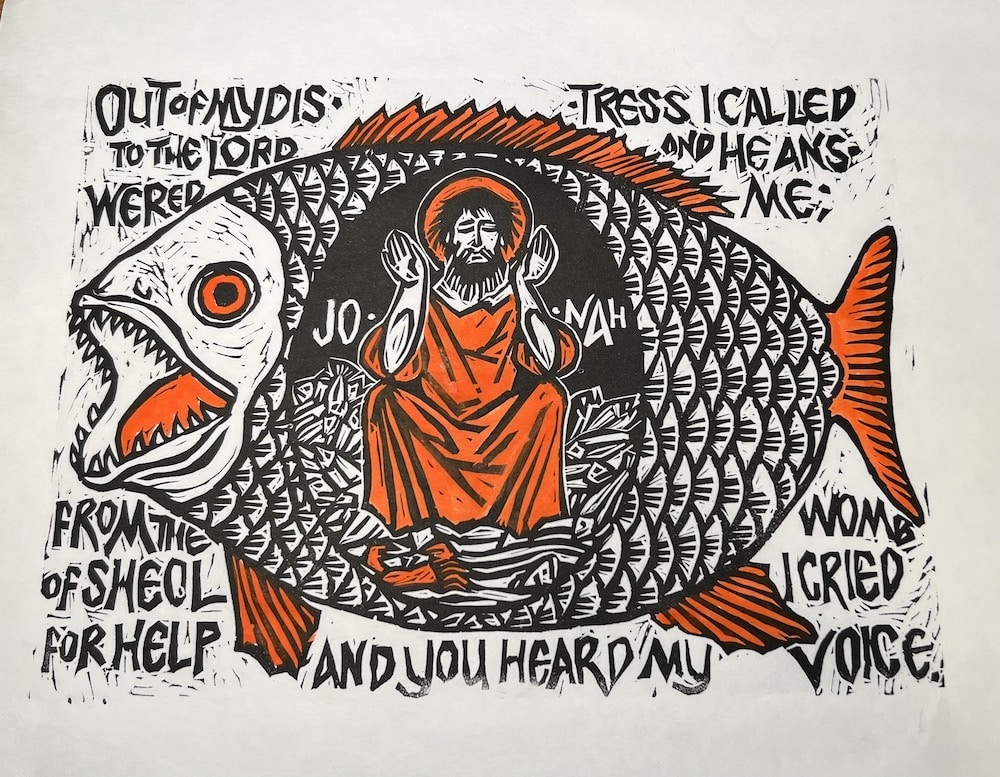

That urgent, undeniable sense of personal presence so many people feel when they spend time before an icon is no accident; it is deliberate, and hard won. When Deacon Rohrbacher is illuminating a manuscript or making a print, he allows himself more artistic license and personal interpretation; but when he’s painting an icon, he follows the age-old rules of the training he received from Shkolnik and from the Byzantine Catholic Jesuit Father Egon Sendler.

“What makes an icon different even from [other] religious painting is that self-expression and creativity are subordinated to the form, which is also the content, of the icon,” Deacon Rohrbacher said.

“It’s the opposite of photography. The stylization works in favor of the icon. It’s not the artist imagining what they look like,” he said.

Personal artistic style and self-expression make way for something more transcendent. It’s similar, he said, to how he serves at Mass as a deacon.

“You don’t make it up,” he said. “Every word I say is in a book. You don’t want to impose your personality on the liturgy.”

Which is not to say that you can’t tell the difference between different presiders.

“That’s a great thing; we’re not robots,” Deacon Rohrbacher said.

But individual interpretation present in icons, just as with liturgy, come about because their power works through individual human beings, and so some individuality is inevitable.

Icons are images that proclaim the Gospel. And images and the Gospel are meant to go together.

“There is something missing in our proclamation of the Gospel without images,” Deacon Rohrbacher said.

He vividly remembers visiting beautifully decorated churches in the early ’80s, and although they were glittering and grand, he was dismayed to realize that nothing visible made them discernibly Catholic.

“I was in a church where somebody had decided they would literally whitewash over the painted Stations of the Cross,” he said.

These pictures might not have been the highest quality art, he acknowledges, but some kind of imagery has always been vital to our faith. You can’t just do without pictures.

These pictures, these icons, are also the fruit of prayer. Deacon Rohrbacher says he always goes to confession and Mass before he begins a new icon.

“It’s hard to say this because it gives people the impression you’re in the studio with your hands folded and your eyes closed in prayer, which is not how it works. But each icon at its truest is the fruit of prayer,” he said.

He describes the process as almost a nuptial act.

“You know how our theology is that the love between parents bears the fruit of a child? The love itself is of value, in and of itself. The child is not a product; the child is a gift,” he said.

It is the same with an icon.

“It’s done with love and prayer and intentionality of service, and out of that, at the end, there’s an icon,” he said.

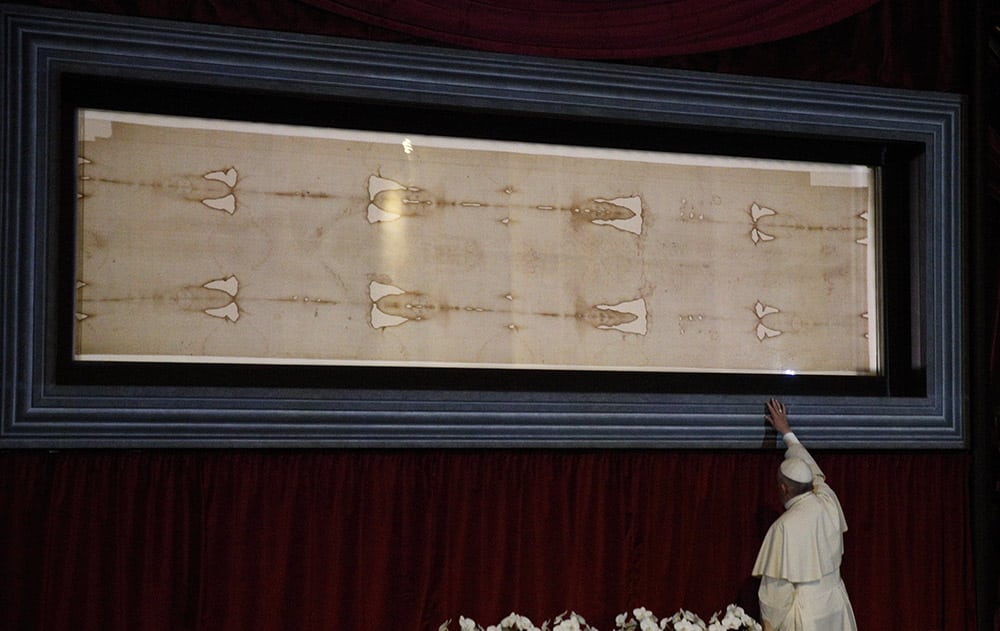

And they are made to be seen — or to be seen through, to be “windows to heaven,” as they have frequently been called — and to help the viewer be seen.

Deacon Rohrbacher recounts one story he heard of how icons, made with this love and intentionality, can function as windows even hundreds of years after they are made.

There was an angry young man, “very alienated from God,” said Deacon Rohrbacher, who happened to visit a museum, the same one where Andrei Rublev’s famous 15th-century Trinity icon is housed.

“He was stopped in his tracks by the icon of the Holy Face of Jesus. What came welling up in his heart was, ‘Why do I hate you?’ And that was the point of his conversion,” Deacon Rohrbacher said.

It happened because he saw the face of Christ looking at him, not with condemnation, but with insistence, and with love.

“He wasn’t confronted in a harsh way, but here’s the face of Christ filled with compassion and love and mercy,” Rohrbacher said.

He was seen. He changed.

Because of this power icons have, he understands why some people try to co-opt icons for political causes, and make them into statements about specific movements or events.

But Jesus is “the still point of the turning world,” he said, quoting a line from the first of T.S. Eliot’s “The Four Quartets.”

“The icon is grounded in Christ, grounded in the Incarnation. The icon provides us with a still point, and it is not meant to be a vehicle for politics. Not that the Gospel doesn’t have profound implications for every aspect of how we live; but because the icon makes Jesus, Mary, the saints and the mysteries of salvation that are invisible, visible to us,” he said.

You don’t want to mess with that, Deacon Rohrbacher said.

“You don’t want to write slogans all over the windows to heaven. You want them to be clear so you can see Christ and Mary and the saints through the images,” he said.

Deacon Rohrbacher is the author of several books, including co-author with Bob Hurd and Bishop Michael Warfel with “A Contemplative Rosary: Praying the Mysteries with Scripture, Song & Icons” (Oregon Catholic Press, $12.10), and “The Easter Proclamation” (Liturgical Press, $79.95) Deacon Rohrbacher explains: “The first Easter I was a deacon, I was incensing a Xeroxed copy of the Exultet in a three-ring binder. I was thinking, ‘We could do better.'”

Deacon Rohrbacher is the author of several books, including co-author with Bob Hurd and Bishop Michael Warfel with “A Contemplative Rosary: Praying the Mysteries with Scripture, Song & Icons” (Oregon Catholic Press, $12.10), and “The Easter Proclamation” (Liturgical Press, $79.95) Deacon Rohrbacher explains: “The first Easter I was a deacon, I was incensing a Xeroxed copy of the Exultet in a three-ring binder. I was thinking, ‘We could do better.'”