The costs of clerical sexual abuse in the Catholic Church are impossible to quantify. The casualties are too many to count. Thousands of innocent souls have been harmed by the sins and crimes of men who ought to have been spiritual fathers and shepherds but who instead preyed upon their sheep like so many wolves.

But consequence of such evil, such sin, has a way of spreading beyond the personal guilt of the abuser or even the grievous and lasting harm done to the victim. The damage is never contained to the evil deed itself, terrible as it may be. Nor is the burden of the sin carried only by the immediate victims, no matter how alone or abandoned they may feel. The consequences of sin radiate through space and time, like the ripples of a stone cast into a placid pool. Sins committed decades ago continue to bear grotesque and putrid fruit generations later.

The material costs of the crisis are easier to quantify, even if they are less important. Billions of dollars have been paid out in reparation for those wicked deeds, and in recompense for failures of bishops who, whether through ignorance, or arrogance, or cowardice, tried to hide the evil deeds of their priests. Not all these failures were due to malice. Some bishops were misled by experts. Some thought they were defending the Church from further harm and scandal. Some were simply not up to the responsibility laid upon them.

What we now know as “the abuse crisis” was already growing in the years between the Second World War and the Second Vatican Council. In the Church, as in many other parts of society, the decades between 1960 and 1980 saw an explosion in cases of child sexual abuse, most of which would not be reported until decades later. While reports of clerical sexual abuse occasionally made it into the press in the 1980s and 1990s — the bishops were secretly briefed on the scale of the problem in the mid-1980s — it wasn’t until the Boston Globe’s reporting in 2002 that most of the world became aware of the scope and scale of the problem.

It has been 20 years since that wave of news broke over the Church in the United States. And it has been 20 years since the American bishops met in Dallas to hammer out a set of policies to prevent abuse and hold abusive priests and deacons (though, alas, not abusive or negligent bishops) accountable. The Dallas Charter, the “essential norms” that codify the charter in Church law, helped the Church in the United States make tremendous strides in protecting children and holding abusers accountable. Clerical sexual abuse in the United States still occurs, but it is mercifully rare and dealt with severely.

When it comes to handling clerical sexual abuse, the Church in the United States has gotten many things wrong over the years. But we have gotten some things right, too. It is as important to glean lessons from the latter as it is the former.

How are our priests?

The Catholic Project (where I serve as executive director) at The Catholic University of America recently published summary results of the National Study of Catholic Priests — the largest study of American Catholic priests in more than 50 years. Several years in the making, the study was the result of a desire to better understand how the crisis of clerical sexual abuse, and the Church’s response to that crisis, have affected priests. In particular, we wanted to investigate the ways in which the Church’s response to the crisis had altered the trust and confidence priests have in their bishops.

The study consists of three distinct survey efforts. First, with the help of the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) at Georgetown University, we took a census of American bishops. This data would give us a sense of how bishops were doing after several (to put it mildly) fairly difficult years. It also afforded us a chance to ask bishops some of the same questions we would be asking priests so that we could compare responses. We received responses from 131 bishops, about 67% of those we surveyed.

The second, and largest, component of the survey was executed by the international polling firm Gallup. This survey was sent to 10,000 priests across the country and received 3,516 responses. To put that in perspective, about 13% of the priests in the entire country responded to our survey. The survey of priests replicated several questions that had been asked on previous surveys — questions about flourishing and well-being, satisfaction in ministry, burnout rates, and so on. What was truly original to this study was the attempt to gauge how much confidence priests had in their bishops (or religious superiors) and why.

The impetus behind these investigations was straightforward. We had heard from both priests and bishops that the relationship between priests and bishops had changed in recent years, and not necessarily for the better. What had been a father-son or brother-brother relationship had, for a variety of reasons, had become depersonalized, more bureaucratic. Was there more to these anecdotal accounts? Had relationships between priests and bishops become strained? If so, why? And how? How might the experience of religious priests differ from diocesan priests?

Our hope was that finding answers to these kinds of questions might give us a better understanding, not only of how priests and bishops are doing, but shed some light on ways to strengthen the bonds of trust and confidence among clergy.

To complement this large-scale survey of priests, we also conducted more than 100 qualitative interviews with priests around the country. These interviews, which are still being coded and processed, were conducted mostly in person or by video and provide insights and detail beyond what the larger study can provide. If the survey can tell us a great deal about what priests think, the qualitative interviews give us real insight into why priests think the way they do. These interviews gave priests an opportunity to express, in their own words, the hopes and joys, fears and anxieties of their lives and ministry.

The findings

The first thing everyone should know about both priests and bishops in the United States is that, on the whole, they are flourishing. To measure “flourishing,” our survey used a series of 10 metrics, each measured on a scale of 1 to 10, which, when combined, give a picture of the respondent’s overall well-being. This composite, developed at Harvard and known as the Harvard Flourishing Index, looks at happiness and satisfaction, mental and physical health, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, and close social relationships.

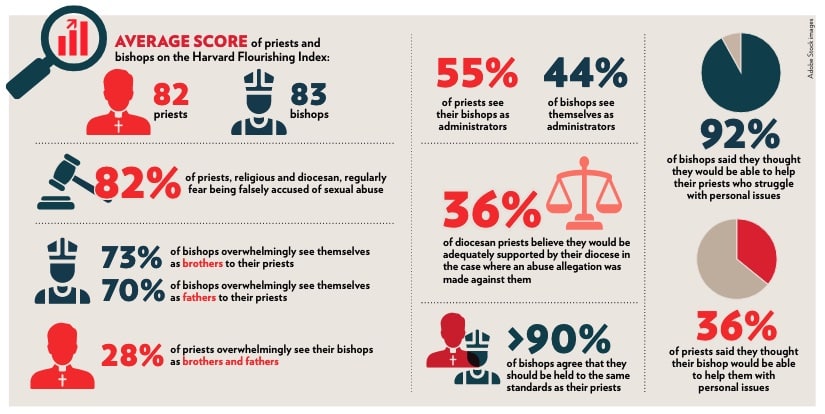

Both priests and bishops scored very high on the flourishing index, with an average score of 82 for priests and 83 for bishops. These scores are well above the average for the general population. There was some variation in flourishing from diocese to diocese, But that variation was relatively low. While we are prohibited from releasing data about specific dioceses (all data is strictly anonymized), flourishing scores were not just high on average, they were consistently high across the country. These findings are encouraging, and they are also not surprising. Previous studies have shown similarly high levels of well-being and satisfaction.

The overwhelming majority of priests genuinely love being priests.

Among priests, higher and lower flourishing scores did correlate with the degree to which a priest had confidence in his bishop or major superior. The correlation was quite strong. Higher confidence in superiors produced higher flourishing scores. This trend held true for every measure of flourishing we tested, even physical health. This is perhaps unsurprising: If a priest doesn’t trust the man to whom he has promised obedience, that is likely to have a trickle-down effect to most aspects of his life. The point is that the quality of episcopal or religious leadership has significant consequences for almost every aspect of priests’ well-being.

It is here that the not-so-good news starts to appear. We asked priests a series of questions designed to measure burnout, asking them to identify whether ministry left them feeling cynical, emotionally drained or worn down. While indicators of burnout were not especially high for priests as a whole, young priests and diocesan priests regularly showed more signs of burnout than older priests and religious priests. Several possible reasons for this discrepancy come to mind.

First, younger priests are still learning the ropes. The adjustment from seminary life to parish life can be hard. With fewer priests today than a generation ago, perhaps more is being asked of younger priests (and sooner) than was the case previously. Perhaps the data represents differing attitudes to hard work between generations. Or perhaps the older priests who were burned out already left ministry and so don’t show up in the data. Perhaps it’s a combination of all of these. Whatever the causes, the elevated signs of burnout among young priests are concerning. It’s not necessarily a bad thing to feel emotionally drained after ministry, but combined with higher levels of cynicism and exhaustion make for a worrying combination.

It is also noteworthy that religious priests show significantly lower levels of burnout than diocesan priests. Two possible reasons for this stand out. First, religious priests live in community and are more likely to have both help and variety in their duties. Isolation is a more and more common problem for parish priests. A second factor is that diocesan priests are far less likely to have confidence that their bishops will support them in the event of a false allegation of abuse. That is a big problem, and one worth looking at in much more detail.

Fear and trust

Eighty-two percent of priests, religious and diocesan, regularly fear being falsely accused of sexual abuse. Eighty-two percent. That is a staggering number. Priests know that a single allegation, even if it is never proven true, can destroy their reputation and bring their ministry to a crashing end.

When the Dallas Charter was implemented in 2002 — with its zero-tolerance policy for priests and deacons who abuse children — it was, by far, the strictest anti-abuse policy in the global Church. Zero-tolerance was also the most controversial policy put in place by the charter. (Many Americans might not realize this, but zero-tolerance is still not the norm for most of the global Church.) Yet today, most priests support the charter’s core policies, with nearly 70% of American priests supporting the zero-tolerance policy, though some 40% of priests think it is too harsh (more on that soon). (Both questions were asked separately.)

What makes priests feel the most vulnerable, and where their confidence and trust in bishops begins to erode, is not the fear of being permanently banned from ministry because of a proven allegation. Rather, they fear being removed from ministry for an allegation that can neither be proven nor disproven, and which leaves them in limbo, with no support and little recourse to recover their reputation, let alone their priestly ministry.

When a diocese receives a credible allegation against a priest, he is immediately removed from ministry. In the case of a diocesan priest, he must leave his rectory, stop presenting himself as a priest, and make arrangements for supporting himself and his legal defense — often all in a matter of hours. All of this quickly becomes public: the parish is notified; the priest’s name is likely published on a list kept by his diocese.

An overwhelming concern from priests is that the low threshold for removal from ministry — a poorly defined and inconsistently applied threshold determined, in practice, by the local review board and the bishop — creates a massive incentive to err on the side of caution and at the expense of priests. This is, in one sense, understandable. Leaving a credibly accused priest in ministry is not exactly a great option, either. At least as far as many priests are concerned, the process as it is currently administered creates every incentive for bishops to treat accused priests, in practice if not in principle, as guilty until proven innocent.

The punishment comes first: suspension from ministry and destruction of reputation — followed, perhaps, by a chance to prove oneself worthy of reinstatement.

In some cases, civil or canonical charges are leveled against the accused; in these cases, he may have to pay for his own legal defense, but at least he gets his day in court. In other cases, law enforcement declines to press criminal charges, for lack of evidence or other expiration of the statute of limitations, but the priest remains suspended by his diocese.

In some dioceses, priests have been removed from ministry for months or even years on the basis of a single, anonymous allegation made in a class action lawsuit against the diocese — an allegation that the diocese cannot even investigate because the accuser is, again, anonymous. While some of those priests are eventually reinstated, many remain, effectively, in limbo.

All of this makes it understandable why 82% of priests fear such a false allegation. And it makes it easier to understand why priests often feel that their bishops sometimes see them as potential liabilities rather than sons of brothers. And the data bears this out.

While bishops overwhelmingly see themselves as brothers (73%) or fathers (70%) to their priests, only 28% of priests describe their relationship to their bishops in the same way. Priests are much more likely to see bishops as administrators (55%), a view only 44% of bishops hold of themselves.

Only 36% of diocesan priests believe they would be adequately supported by their diocese in the case where an abuse allegation was made against them. Only 51% thought their bishop would support them and 61% thought they would be able to prove their innocence. Perhaps most starkly, while 92% of bishops said they thought they would be able to help their priests who struggle with personal issues, only 36% of priests thought the same.

Interestingly, while religious priests report regularly fearing a false allegation at almost the same rate as diocesan priests, they are much less concerned about what would happen to them if such a false allegation were made. Religious orders are required to provide legal counsel for their members. Short of criminal conviction or laicization (both of which would require clear demonstration of guilt), religious priests know that their communities will take care of them and provide for basic needs like food and shelter.

For all of these fears, remember, priests remain supportive of the central policies of the Dallas Charter, including zero-tolerance. When priests did express concern about the strict policies of the charter, they were all but unanimous in support for zero-tolerance when it comes to sexual abuse of children. Where things get a bit more complicated, and where priests would very much like greater clarity, are in less straightforward cases involving “boundary violations” or “vulnerable adults.”

Add to all this the fact that allegations against bishops have rarely been handled with anything like the severity with which bishops themselves handle allegations against priests — even under the new law on episcopal accountability put in place by Pope Francis in 2019 (Vos Estis Lux Mundi).

Most bishops seem to understand all this, even if there is much work to do to address the strain it has put on priests’ willingness to trust their bishops. More than 90% of bishops agree that they should be held to the same standards as their priests. And bishops are even more likely than priests (35% vs. 23%) to believe there are still unrevealed abuse cases within the Church. Only 21% of priests believe that the abuse crisis in the Church is “basically over.” It is sobering that among bishops that number falls to only 15%.

What comes next

The bishops of the United States are currently in the process of revising the Dallas Charter, as they do every few years. Strengthening due-process protections for accused priests, taking steps to ensure that accused priests will be taken care of (at least until they have been convicted of or admitted to a crime), and finding ways to ensure clarity and consistency about relatively new legal categories of abuse (e.g., boundary violations, sexual activity with vulnerable adults) ought to be among their priorities.

Such changes would make the charter stronger, not weaker. Greater clarity and consistency in the handling of allegations in the initial stage would not only benefit accused priests and help calm the fears of the majority of priests who fear a false allegation, but it would also seem to be a benefit for bishops.

Removing accused priests from ministry and returning them to ministry is the responsibility of bishops. In many cases where clear proof of guilt or innocence are not forthcoming, the bishop has to use his best judgment, balancing the need to take allegations seriously with the need to protect the rights of the accused. Such decisions can be excruciatingly difficult. No bishop wants to keep an innocent man out of ministry. And no bishop wants to return to ministry a priest for lack of evidence only to have that priest offend again. And no bishop wants to put his own ministry in jeopardy by making the wrong judgment about this or that priest.

Again, strengthening due process protections and restoring trust would benefit both priests and bishops.

The stakes are high

Of all the casualties and costs of the abuse crisis, erosion of trust is one of most widespread and lasting. Restoring trust is essential if we hope to find healing in the Church, here and now. But the stakes are really much greater than that. The loss of trust between the members of the Body of Christ is not just a wound against communion; it is not merely a drag on the well-being of our clergy (and laity). A lack of trust hamstrings the Church in her most essential mission.

At the most basic level, the proclamation of the Gospel is accomplished by the testimony of witnesses. If the witnesses to the Gospel are untrustworthy, her mission to the world is stymied. Where distrust spreads, hope is clouded and faith recedes. Ultimately, the greatest cost of the abuse crisis is measured in souls.

Stephen P. White is the executive director of The Catholic Project at The Catholic University of America.