Postponing the beatification of the late Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen likely has surprised and distressed many Catholic Americans, especially those who remember and still admire him.

Postponing the beatification of the late Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen likely has surprised and distressed many Catholic Americans, especially those who remember and still admire him.

This is what possibly was behind the decision to delay the Church process declaring him “Blessed” and setting him more directly on the path to sainthood.

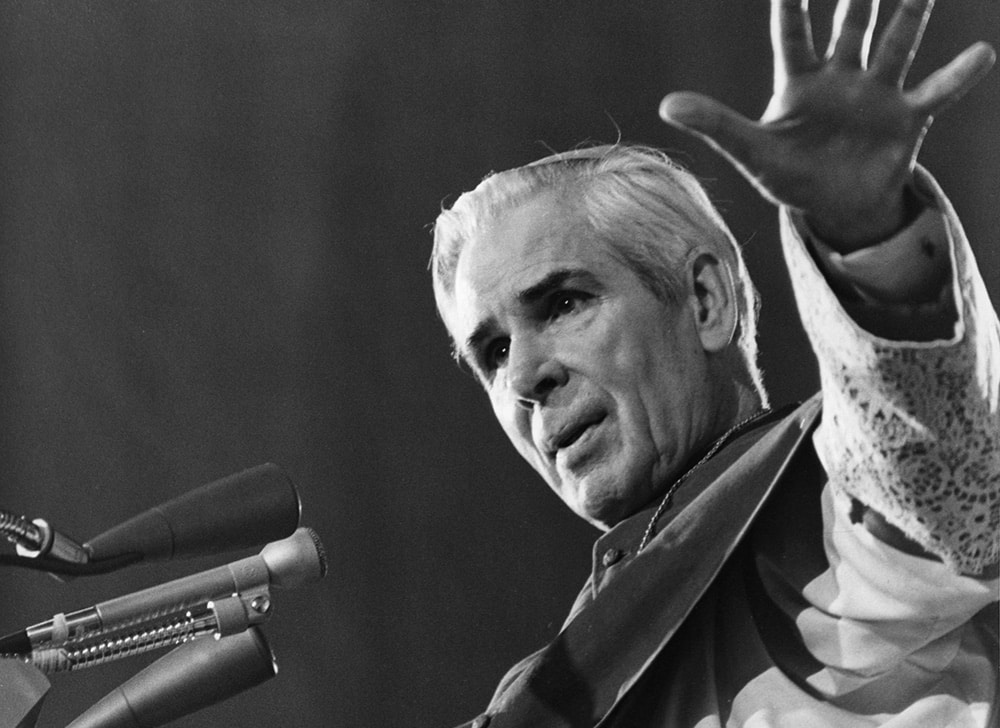

Many Catholics in this country still recall the deceased archbishop as a television figure in the past. For five years, he was the centerpiece of a weekly program, on Tuesdays, in prime time, on nationwide television. He was remarkable. For one hour, he held the stage, without notes, speaking eloquently and convincingly about the Catholic faith.

Public reactions to the show also were remarkable. His high ratings excelled those of competing shows where the leads were Milton Berle, the top comedian of the day, and the legendary singer Frank Sinatra.

The show ultimately was discontinued, but eventually EWTN brought it back. As a result, for many Catholics, Archbishop Sheen’s name remains a household word.

Forgotten is the fact that he was not just a television personality. He was a diocesan bishop. From 1966 to 1969, he headed the diocese of Rochester, New York, where he was responsible for the Church and for its priests.

From this period, and from this responsibility, may come the reason for stopping his beatification, at least for the present.

Some news reports, very plausible given the times back then, say that he accepted into service in Rochester a priest who had been accused of child sex abuse elsewhere in the country. Others say it was Sheen’s successor who made the appointment, but nevertheless, nowadays, such acceptance on the part of any bishop would be shocking — grounds for his removal. Indeed, any bishop today who would welcome into his diocese’s priestly service a priest with a questionable record should have his head examined.

This would be today. That was then. Consider the differences between these two periods in history, one by one.

First, sexually abusing a minor, by anyone, priest or not, male or female, was regarded only as a breakdown in the limits, customs or rules placed upon a person’s behavior. If an adult molested a youth, it basically was assumed that the adult yielded to temptation. The Church saw it as a moral issue. When a priest failed in this regard, he was told to sin no more. Bishops sent priests to monasteries for long retreats, hoping that a heartfelt return to Christian spirituality would solve everything.

Offenders were not sent to psychiatrists precisely for pedophilia. In those days, pedophilia was not a defined medical diagnosis. Doctors saw sex abuse of youth as evidence of something else wrong with the adults: too much drink or drugs, fatigue or an underlying emotional issue unrelated to child sex abuse.

Physicians routinely advised bishops to reinstate priests accused of sexually abusing youth, invariably saying that if “Father” promised to control himself, accept treatment for a fundamental disorder, and put his value system in order, the problem would not recur.

What about the victims? Hard, and heartbreaking, now to believe, but most people, even if appalled, assumed that children would cope without experiencing serious, long-term harm.

No one reported cases to police. Many jurisdictions had no offices for child protection, whatever the concern. Unless grave bodily injury, kidnapping or some other pronounced crime was part of the event, the law left policing to parents, school principals or the like.

Cases deliberately were concealed, just as families hid pregnancies outside wedlock or, in modern terms, addictions and members with intellectual or physical challenges. Professions carefully kept malpractice secret.

Since 1969, medicine, the Church, civil authority and the culture have come a long way. Look at the strength today of the “Me Too” movement.

Evil is evil, wrong is wrong, but moral assessments vary and grow as people think and learn. Views about torture or slavery are examples. Human minds are imperfect. Realizing this helps us to understand how bad things happened.

Msgr. Owen F. Campion is OSV’s chaplain.