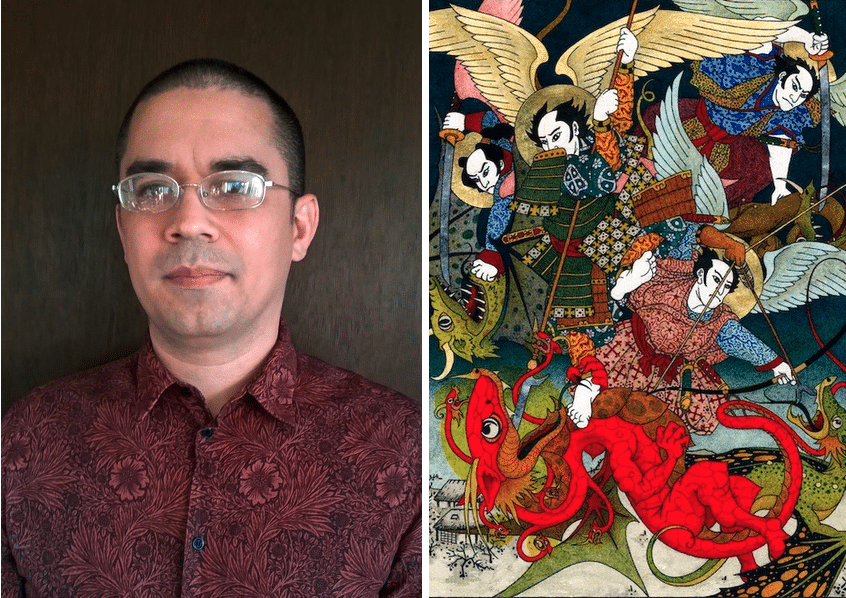

Daniel Mitsui likes drawing on calfskin vellum the best.

It’s popular with artists who, like Mitsui, create works in a medieval northern European style. But it’s not mere tradition or attachment to history that makes calfskin so appealing to Mitsui.

“It’s really, really, really nice,” he said. “It’s a very precise medium because, on a microscopic level, it’s an organized layer of skin cells. You get a more precise line, and you can make corrections easily by scraping away a layer with a knife.”

Try that on paper made from vegetative matter, and you’ll tear your picture up. But calfskin vellum is forgiving.

“People sometimes say, ‘How can you be so precise?’ That’s part of the secret. You draw on a better surface,” Mitsui said.

Mitsui, 41, has spent decades doing the work of carefully sorting, modifying and balancing tradition with innovation — or, more precisely, “combinations of influences, rather than wholly new ideas,” he said.

His work is distinctly medieval but brings in elements of Persian, Celtic and Japanese art.

“I think of it as a living style, rather than a historical one,” he said.

“In religious art, there’s a requirement that you try to uphold tradition in some manner, but I think that tradition is mostly in the content and the arrangement of the picture. It’s not really stylistic, so much as what you are showing, and with what associations,” Mistui said.

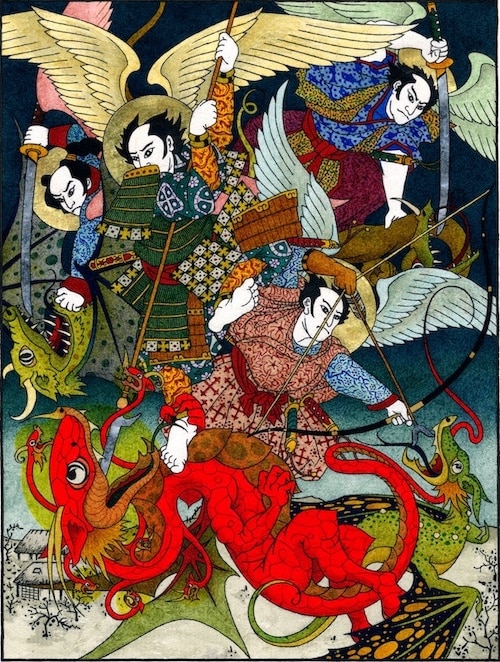

Thus he brings his audience “Great Battle in Heaven” in the style of a Japanese woodblock print.

On his site, he explains how he synthesized the appearance of the angelic warriors, who look like the heroes in prints by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, with a composition from one of Albrecht Dürer’s apocalyptic works. The result is at once arrestingly unusual and weirdly familiar, like a vivid but coherent dream where the mind feels free to draw on any meaningful image.

Church Fathers

He is aware that not every viewer will be well versed in the Patristic writings and artistic conventions that enrich his work, so he tries to write descriptions to help the viewer understand more fully what they are seeing.

“It’s something I’m not as on top of as I’d like. I’m a relatively fast artist and a relatively slow writer,” he said. “I’m always behind.”

He said that medieval art is full of well-established symbolism, which is not necessarily obvious when you first look at it, but a little bit of analysis will provide the background to show how well it corroborates with what the Church Fathers have always taught.

“I very strongly value tradition as a theological concept, as the basis of Catholic epistemology. It’s how we know what we know as Catholics. That underlies my artwork; that’s part of what I’m trying to communicate,” he said.

But his work enjoys enormous appeal across a wide range of audiences because the images themselves are so compelling. And remaining faithful to tradition doesn’t mean limiting his scope.

Aesthetic notions

“There’s really very different views on artwork even in traditional Catholicism,” he said. “If you even go back to the 12th century, the Victorines and the Cistercians had very different notions of aesthetics. I can’t just say, ‘My work depicts traditional Catholicism.’ Well, which part of it?”

The last thing Mitsui wants to do is pitch his work to a limited audience bound by nostalgia or a dogged thirst for familiarity. He feels a duty to avoid that.

“My conscience will not allow me to make boring art for God, at least not purposely,” Mistui said in a lecture.

Mitsui has added in more innovations than stylistic ones: He also sometimes draws on both sides of the vellum, which is thin and translucent. In the “Great Battle in Heaven,” he said,

“In some medieval works of art (such as the Cloisters Apocalypse), the seven-headed dragon’s seven diadems are depicted as green haloes; here I have rendered them with transparent layers of greenish-yellow ink, suggesting a bioluminescent glow.”

Many people who buy his original works put them in double-sided frames, so the light can shine through. He’s not sure if he invented this process, but he knows it’s not common.

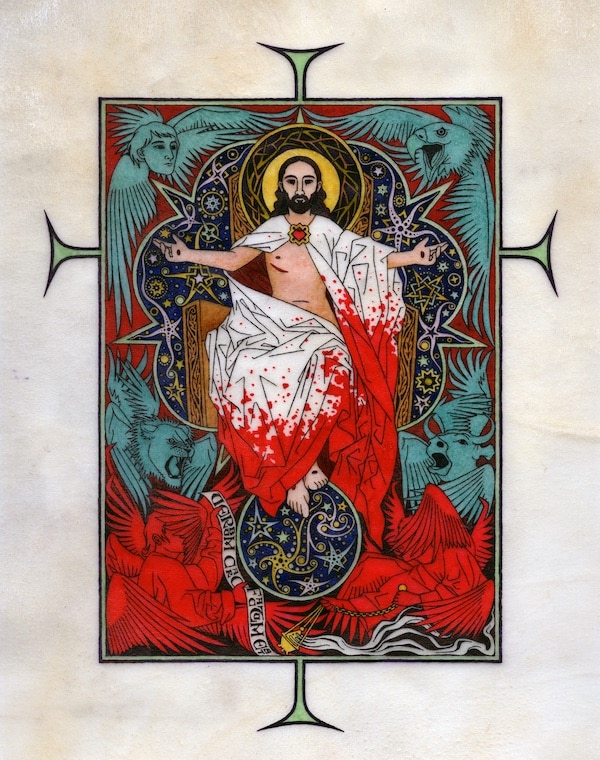

In another recent work, done (like the vast majority of his work) on commission, he depicts a very specific theological idea, perhaps in a way that hasn’t been done before. His drawing “Jesus Christ in Majesty with Cherubim and Seraphim” was intended to illustrate “a connection between the crucified and the glorified Christ, showing that they are one and the same.”

Through some back and forth between him and his patron, he settled on an image of Christ, arms outstretched in the shape of a cross, his feet on a globe and his body surrounded by a geometric starburst of cosmic designs. These are all familiar, traditional elements of an ages-old icon, which Mitsui has drawn versions of many times; but in this piece, he clothes the Risen Christ in a white robe that is drenched and spattered in scarlet blood, drawing from the apocalyptic prophesies of Isaiah and St. John. The four evangelists seem to be crying out, and the angels at his feet cover their faces with their own wings. It’s a fascinating, terrifying, gorgeous image, and it’s hard to look away.

Summula Pictoria

Not all of Mitsui’s work is so heavy with portent. He also designs more mundane pieces like bookplates, coloring books, fabric designs and typefaces, as well as biological and other secular work, including heraldry and literary and historic illustration.

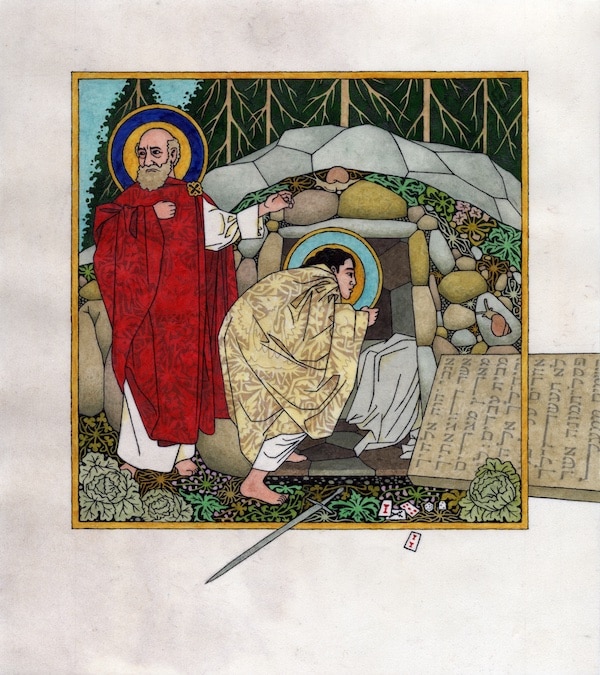

And many of his images depicting religious scenes are movingly tender, like the sensitively-rendered “John and Peter at the Tomb,” which shows a barefoot St. John in the act of fearfully crawling inside the empty tomb of Jesus, while St. Peter worriedly clutches his robe and looks back. The earth is cut away in almost a cross-section, revealing snails, perhaps moss or algae and other herbage, and a few cabbages growing around the open doorway, an abandoned sword and a scattered game of lots tumbling out through the picture plane. The figures in the foreground and the background are deliberately flattened to capture a distinctively medieval feel.

Again, this stylistic choice isn’t simply a matter of aesthetic preference. Mitsui deliberately doesn’t employ linear perspective (the more three-dimension perspective that makes post-medieval art look more naturalistic). He has written in great detail about why this “flat” perspective, which can appear at first glance like an unsophisticated, less realistic portrayal of the world, is actually an excellent way to convey eternal and invisible truths about the spiritual world as it is understood by temporally-bound humans.

The picture of Peter and John is part of a series Mitsui began in 2017: The “Summula Pictoria: a Little Summary of the Old and New Testaments.” He said his commissions tend to be the same themes over and over again — certain devotions and favorite saints — but he has always wanted to illustrate the Old Testament.

“I realized I need to start actually taking control of the art I’m drawing,” he said.

So, rather than waiting for some patron to request those scenes, he has drawn up a list of the 244 most important images, and is opening them each up for commission. He expects the entire project to take over a decade.

Fascinated by sacred art

Mitsui has other irons in the fire, too. Before he launched his professional career, he studied many forms of art (drawing, oil painting, etching, lithography, wood carving, bookbinding, and film animation), and it was then, when he became baptized at age 22, that he made the conscious choice to pursue sacred art, rather than animation or some other field. He had always been fascinated by sacred art, but his conversion opened up new worlds of possibility.

“It was kind of a new thing for me to be looking at [sacred art] through a religious lens and not just an aesthetic one. It was kind of thrilling, this big world that was now so much more meaningful,” he said.

But he does hope to return to animation some day.

“I’ve drawn projects in the back of my mind,” he said.

He realizes that his style, so meticulous and precise, doesn’t lend itself well to film animation, which requires the artist to draw very quickly, without a lot of ornamentation.

He would like to do a hand-drawn animated short of one of the visions of St. Hildegard, though. “That’s the one I’ve thought about the most. I have no idea where I would get the capital to get that together,” he said.

One other project he has recently finished is a book of original poetry. It’s titled “The Wretch on the Gallows Tree: Rhymes and Carols” ($16). It will include a few illustrations, but is primarily “carol and hymn texts on the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, following the sequence of the liturgical year.” The book was released in early March.