Have you read the Harry Potter books yet? Maybe your children read them, or want to, but you feel uncertain as to whether or not you should let them. Or, you’ve heard about them and need a guide to help you decide if your family should read them.

Some of you have not read the books, so my plan is to give away as little of the plot as possible, while still letting you know certain things so you can decide whether the books should be read in your family.

Here’s something interesting I’ve noticed about Harry Potter and Catholics. Many Catholics don’t think much about Harry. Their children go to school, the classmates talk about Harry Potter books and most parents assume since Jenny’s mother lets Jenny read the books, and since Jenny’s mother is careful about things, the Potter books must be OK.

In certain Catholic circles, the rumors have gone around for years that Harry Potter is bad.

Although Harry Potter is criticized as being a less than perfect character, I’ve never heard anyone complain about the villain Lord Voldemort being less than completely evil. Voldemort has been described as pure evil, but author J.K. Rowling has given her villain some redeeming merits.

For example, when he has the power to kill a defenseless hero at the end of the fourth book “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire” book, Voldemort gives the boy the chance to defend himself.

Worth another look

Parents who hear about the Potter books from trusted Catholics on radio and TV avoid the books, wish they weren’t in the library, tell other parents to avoid the books and even post warnings online. I know. I was one of those Catholic parents on the receiving end of such e-mails, and I, too, was against the series — though I had not read them myself.

Later on, Catholic parents whom I considered thoughtful and discerning said positive things about Harry Potter. Then I began to give the matter another look. Why would these parents say the Potter books were OK, and even admit they were reading them to their children, if the books were evil — as I believed?

I read the books and changed my mind about what they contained. I discovered a world of Catholic underground pro-Harry supporters.

Bible and Catechism

Naturally, the Bible and the Catechism of the Catholic Church reject all practice of divination and sorcery. The Harry Potter books are fictional works, which portray magical practices fictionally.

The potion recipes are never given in full, and the ingredients mentioned are things that don’t really exist. The future cannot be predicted; the past cannot be changed. No one calls on a demon for their spells; they call out Latin sounding words. If anyone tries this at home, nothing happens, as one would expect.

The magic in Harry Potter is fictional, so the Bible and the Catechism wouldn’t condemn it. Harry Potter is a story, a work of an author’s imagination, a modern-day parable. It’s just like how attending a child’s magic show does not put one in danger of being involved in “real” sorcery.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church (see Nos. 2116-17) talks about divination, and in Deuteronomy 18:9-12, going to fortune tellers and palm readers, among other things, is forbidden.

The Bible and the Catechism reject real sorcery, and forbid us from trying to call on demons, but again, that’s not what Harry Potter is — Harry Potter is a fictional story.

Positive depiction

I don’t think Rowling’s books are perfect. On the other hand, I find it amazing a children’s story published in our times has no smoking or drug usage; no homosexuality or mixed-up sexual feelings; no TV at school, movies, Internet, computers or instant messaging; there is very little swearing, very little kissing, not even a token single-parent family.

Harry (before being orphaned), Ron, Hermione, Draco — in fact, all of the main children — have two parents, one male and one female. In the world of children’s books today, this is unusual.

Of course, many people worry about the practicing of the dark arts. Hang on, why would witches and wizards need to practice defense against the dark arts? If everything they do, as critics claim, were a dark art, there’d be no need.

In the Hogwarts world, there is a battle going on and the good side must fight against the bad. Just as soldiers need to practice their battle skills, so must the students at Hogwarts practice to fight their enemy.

If we look at the dark arts as Rowling intended evil uses of magic and we compare the dark arts to sin and temptation, then we know we need to do something to prevent their intrusion in our lives.

Do we fight sin? Resist temptation? Do we practice the skills needed to overcome the black or dark tendencies in our lives? Or do we operate as if we can go about our daily lives, and, magically, our sins and temptations will go away with no effort on our part?

What are we teaching our children? Are we teaching them how to fight life’s battles, or are we indulging them by allowing them to play and socialize without learning the responsibilities of putting others first, of putting work before play — in other words, developing their character — which is more important than exuding a positive self-esteem?

Hone your skills

Another point about practicing: even though Harry has skills at flying and playing Quidditch, a wizarding game similar to soccer or basketball on broomsticks, he still practices the game and works at improving his skills. We, too, must practice our skills and hone them for the work we must do to build up the kingdom.

The dark-arts lessons represent fighting to resist sin and temptation in our lives. One allegorical element of J.R.R. Tolkien’s “One Ring” in the legendary “Lord of the Rings” series is its power of temptation. Characters fight over the ring, and must work out what to do with it. In C.S. Lewis’ “Chronicles of Narnia,” the children must figure out how to release Narnia from the grasp of the evil White Witch.

Love protects us

The deepest, most powerful expression of good in the Harry Potter books is the self-sacrificing love which Lily Potter, Harry’s mother, showed in protecting her infant son from Voldemort, offering herself as a substitute for her only son’s life, and ultimately giving up her life.

Her loving sacrifice is a charm powerful enough to prevent Harry’s death as an infant, and this love also saves him in his encounters with Voldemort in school. Harry and his friends catch the train at King’s Cross Station. It’s the real name of a station, but the choice points to something Rowling wants to say. The “cross of the king” changes the direction of our lives, too, doesn’t it?

The Blood of the Lamb, the Eucharist, the Blood of Christ saves us. A story where blood saves should seem very familiar to us. Christ’s blood saves us. Lily’s blood saved Harry.

Lily’s inoculation of love may also have protected Harry from the very unloving and uncaring environment of his uncle and aunt’s home. After 10 years of being ignored, pushed around and scolded, Harry is still a normal boy, who is neither scarred by his rough treatment, nor bitter about his lack of a loving home.

At the end of the day, the “Harry Potter” series is a story, and because it reflects all true stories, some parts will ring true. There are truths to be discovered and no reason why Catholics can’t discover them.

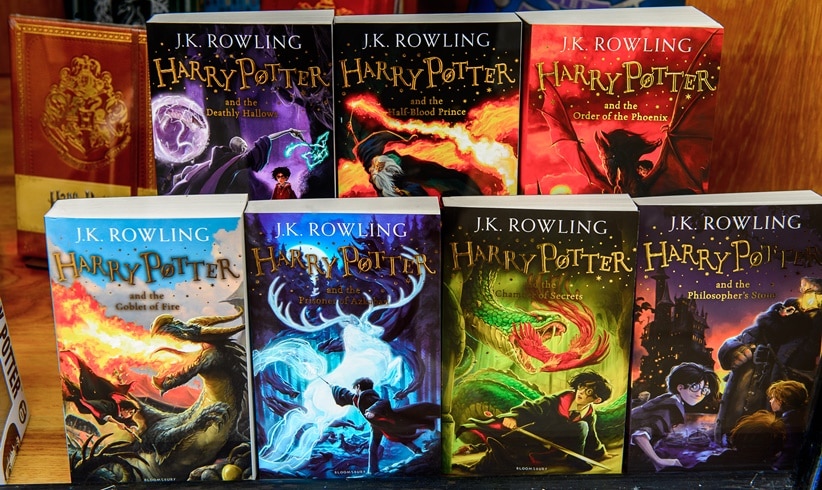

‘Harry Potter’ chronology

September 1998: “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone”

June 1999: “Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets”

September 1999: “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban”

July 2000: “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire”

June 2003: “Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix”

July 2005: “Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince”

July 2007: “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows”