Editor’s Note: This story reports on a community that uses the word “fat” as a value-neutral descriptor. To best reflect this perspective, OSV has retained the usage of that language.

Of the 108,485 adults received into the Catholic Church in 2013, one was a woman whose parish was sponsoring a weight-loss program. She knew this because, attending church events over the course of her time in RCIA, people would tell her about it, often as soon as they met her.

“And it kept happening! I lost count of how many people told me,'” she told Our Sunday Visitor. She found that the encounters made her journey into the Catholic Church, already a vulnerable time, needlessly traumatic.

“I felt that all they saw was a fat person instead of a person who was looking for Jesus. I dreaded going to events because I knew someone was going to bring up” the program. When meetings were announced at the end of Mass, “I felt that everyone was looking at me and the priest was telling me that I should go.”

In June 2015, Kateri Taylor, director of religious education at Our Lady of Mercy Parish in Potomac, Maryland, was in Virginia at the funeral of her uncle and godfather when her parents’ pastor, a good friend of her family, arrived with another priest, whom she’d never met.

“I think his first comment when we were introduced was, ‘Wow. You’ve got some good weight there’,” Taylor told OSV. “Then when we were getting food he made a ‘big belly’ motion and asked if I was going to eat a lot.”

Taylor didn’t know how to respond.

“I’ve been taught my entire life to respect priests, and I couldn’t think of anything respectful to say. My brain just froze.”

Taylor may have been just about as prepared as any Catholic to discuss how Catholics and all people of faith relate to issues of weight and treat people who are fat. It’s a tangle of issues drawing in everything from U.S. diet culture, health concerns and beauty standards (and the people who determine them) to Catholic understanding of the body, merciful love and how virtuous behavior works.

Those who hunger

In U.S. culture, people tend to be mistreated based on race, class, immigration status, age and weight. The Catholic Church is pretty vocal in speaking out on four of these areas, and Amanda Martinez Beck would like to change it to all five.

Beck, a 32-year-old writer who lives in Long View, Texas, has, in her words, always had an appetite bigger than her frame. Her parents first introduced food restrictions when she was in early grade school.

“I remember at least one trip to visit a dietitian at Children’s Medical Center in Dallas as my parents tried to get my eating under control,” Beck told OSV. “I remember hearing, ‘I don’t want you to die of a heart attack at age 20,’ from my dad, tears in his eyes. There were a lot of fear tactics involved, based in genuine concern.”

But instead of motivating her to lose weight, Beck said, “I just decided that wasn’t something I wanted to spend my time on — while hating myself for not caring enough to ‘be fit’.”

Beck is now a wife and mom with a fourth baby on the way. Her pre-pregnancy weight of 270 pounds, combined with her modest height, puts her body mass index at “extremely obese.” She dedicates her writing to two primary areas: Jesus and weight.

The two are deeply connected for her.

“My journey to Jesus started with Communion,” said Beck, who entered the Catholic Church with her husband at Easter 2015. “When I was 3, my parents and I attended Odessa Bible Church in West Texas, and Communion was served every week. I wanted to be part of this eating and drinking, and it drew me into the Body of Christ.” In college, Beck found a community church that offered Communion. She “couldn’t get enough of taking Communion weekly,” she recalled. And so it was the Eucharist that ultimately drew her to Catholicism.

“I’d always viewed my appetite for eating as unhealthy until I was able to frame my story as being drawn into the Catholic Church through my appetite,” said Beck. “Eating and drinking draw me in to intimacy with God.”

Dappled people

Beck’s writings, which appear on her website “Fat in Church” and on other outlets, are a Catholic permutation of a cluster of social trends that share a range of labels: body positivity, size acceptance, fat acceptance and healthy at every size.

Lauren Jones, a 34-year-old Catholic stay-at-home parent and student from Carlisle, Pennsylvania, told OSV that these terms share a core of accepting oneself as worthy of love.

“Body positivity leans more toward being intentionally kind to your own body, where size and fat acceptance are specifically about making peace with where you are at this given time — no matter what your size is — even if you are fat,” said Jones, who described herself as “fat since I was young” and noted that issues including eating disorders, self-esteem, mental illness and the cultural beauty ideals are all wrapped up in this. “Health at every size is a concept that deals with separating health from the number on a scale, and physically caring for your body with nutrition, exercise or rest.”

While these concepts emerged from secular feminist culture, the communities they foster, particularly online, have a Christian subset, where activists such as Beck and J. Nicole Morgan speak specifically to the fat experience in communities of faith. Morgan, 33, earned a master’s degree in 2014 from Palmer Theological Seminary at Eastern University near Philadelphia, which is affiliated with American Baptist Churches USA. She is writing a book on fatness and faith.

“I frequently hear from people — especially women — with stories similar to mine who also have felt so much body-shame from the church,” Morgan told OSV. Her experiences include frequent reminders that gluttony and sloth are deadly sins, church seating not built to accommodate her size, and even the observation that her body was a counter-witness, because God couldn’t make her thin.

Morgan’s story finds a secular echo in Mariah Carrillo, another fat acceptance writer who grew up in an evangelical church but who left the practice of organized religion entirely after her college weight gain put her at odds with the ethos of her strict religious upbringing.

“My experiences with body positivity mirrored my experiences with faith,” Carrillo told OSV. “I needed more room. I needed to be allowed to take up space, both in a physical sense, and in a spiritual one. I needed to be able to ask questions and expect reasonable, thoughtful answers.”

Catholic author Simcha Fisher (“The Sinner’s Guide to Natural Family Planning,” OSV, $9.95) doesn’t identify with the size-acceptance movement, but has written about her own struggles with weight. “It really is unjust to be such an easy target,” she told OSV. “When you’re fat, your sin — if sin is, in fact, what causes your extra weight — has such visible effects. The woman next door can lie and gossip all day long, but it doesn’t stick to her like eating pie all day long will stick to me!”

Take, eat

These stories raise questions for the Catholic Church: Are Catholics, intentionally or not, more accepting of fat people than other Christians? Have Catholics been co-opted by strains of belief and practice they don’t even realize are extraneous to what it is to be Catholic?

“I’m a Catholic convert from an evangelical background, and truthfully I’ve noticed less diet focus and body negativity since becoming Catholic — particularly I see it absent during the homily, when I’ve in the past heard well-meaning, but harmful comments in sermons,” said Jones. She offered a theory for what underpins her improved experience in this area. “Catholicism separates itself from culture in a way that evangelicalism does not, and it’s in the nature of the Church to challenge what is accepted by society.”

In this case, that could be an obsession with thinness versus a God who, as priest-poet Gerard Manley Hopkins put it, created a splendid variety of “dappled things.”

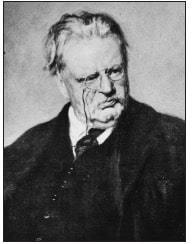

Or it could be the embrace of diet culture versus what Catholic apologist G.K. Chesterton, himself no ascetic, famously said: “In Catholicism, the pint, the pipe and the cross can all fit together.” This is also the Church that made St. John XXIII pope.

“It puts me in community,” Beck said of her experience of sacramental life. “I feast with my brothers and sisters instead of gorging myself alone.” Beck and Fisher both noted that Catholics who go all in for weight loss programs are buying into yet another form of the “prosperity gospel.”

Morgan concurred: “There’s a lot of Protestant work ethic issues at play here. That value says you have to work hard to be good/successful. If you enjoy your life/body as it is, there’s probably something wrong with you.”

Protestant work ethic. Prosperity gospel. Pope Francis might say neopelagianism.

One person with a richly developed sense of the Catholic Church’s relationship with eating is Jeff Young, who authors a blog and podcast called “The Catholic Foodie.” He shares recipes and spiritual wisdom.

“Food is life. And this goes beyond the fact that we all have to eat. If you look back in the Old Testament you find that food plays a big part in the story of salvation,” Young told OSV. “Food was never just about diet and energy. Food was about life and relationship.”

Again, the Eucharist, what the Second Vatican Council calls “the source and summit” of Christian faith, is a meal.

On the line between joyful celebration of God’s abundant gifts and the sin of gluttony, Young said, “It’s challenging; I’ll be honest. I like celebrating. And I live in New Orleans where we utilize any excuse we can find to throw a party, replete with good food and good drink. And good music. We might never do this perfectly, and I think that’s OK. This is one area where we can apply that famous quote by Chesterton: ‘If a faith is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.'”

Young sees practices such as fad diets as reinforcing “the Cartesian dualism that has us believe that we are split from our bodies.” Yet, he said, “there is fear of obesity, and we — as a culture — are quick to condemn it in others and push ourselves to crazy extents, though diet, exercise and even surgery, to prevent obesity in ourselves.”

Mercy embodied

For Beck, this awareness that everyone has body hang-ups led her to believe the Year of Mercy, called by Pope Francis, is a great time to talk about body positivity and fat acceptance. She had originally entitled her website “Fat Privilege,” a twist on a phrase, “thin privilege” — the treatment people enjoy in society by not being fat — used in the size-acceptance community. What she meant by fat privilege is captured in the official prayer for the Year of Mercy:

“You willed that your ministers would also be clothed in weakness in order that they may feel compassion …” goes the prayer.

“You willed that your ministers would also be clothed in weakness in order that they may feel compassion …” goes the prayer.

And so, in being fat, Beck said she understands with compassion, not only people who’ve been mistreated because of their weight, but others who’ve been marginalized. Self-acceptance and acceptance of others are inextricable.

“The standards we hold our bodies to in our culture have ramifications on so much more than a body’s health or image, because it affects every strata of our society — from the elderly to the unborn — that we demand physical perfection. And it affects the way that we live,” said Beck. “It’s accepting that we’re loved and that God has mercy on us without our meriting anything.”

Taylor, whose weight gain was triggered by the onset of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), also sees the heightened sense of compassion brought on by her size, something she carries into her parish ministry.

“It does let me see the difference in people’s treatment in my broader life,” she said. And reflecting on an experience such as the priest at her uncle’s funeral, she realizes she doesn’t know other people’s weight and body struggles any more than other people can’t see her healthy eating habits or spending 6-8 hours a week at the gym.

“I actually put a lot of effort into my health,” she said, noting that PCOS has not only caused her weight gain but also her infertility. “When people hear that I can’t have kids, they assume my infertility is caused by my weight, rather than being caused by a separate disease.”

But a person shouldn’t have to be dieting and exercising in order to deserve love, Morgan points out.

“There’s something called a ‘good fatty’,” she said, invoking another term from the size-acceptance world. “That’s a person who eats lots of vegetables and runs 10Ks and dresses really well. They look fashionable, and they do all the ‘health’ stuff they’re supposed to do. Society accepts them first. At least theoretically — they’ll usually find a reason why even a ‘good fatty’ isn’t quite doing enough. Choosing to have a bowl of ice cream or to watch an hour of TV from the sofa or to wear sweat pants in public are all things that lower the ‘goodness’ of a fat person in many people’s eyes.”

Which, she added, is ridiculous from a faith perspective and not indicative of unconditional love. Whether someone is a “broccoli-eating, bike-riding, snazzy dresser, or McDonald’s-loving TV fanatic who can’t get enough of the comfy sweats, or some combination of all that — all are people loved in the image of God. Both people have the capacity to love God, love their neighbors and make God’s love present in the world.”

And whether questioning standards of beauty or the treatment of others, the issue that most often bogs down any discussion is health.

“You just have a complicated mess of people trying to figure out what ‘right’ is in terms of our bodies and judging each other over it,” Morgan said. “My current pastor is also in med school and has been supportive of what I do — which has been healing in so many ways.”

This is my body

One possible model for a measure of health in keeping with Catholic teaching comes from Beth Haile, a former assistant professor of moral theology, who recently left the faculty of Carroll College, a Catholic liberal arts college in Helena, Montana, to raise her kids full time.

Haile, 32, earned a Ph.D. from Boston College in 2011, and her dissertation sought to apply a moral dimension to the subject of eating disorders. She drew on the thought of another Catholic widely regarded as fat, St. Thomas Aquinas.

Haile, 32, earned a Ph.D. from Boston College in 2011, and her dissertation sought to apply a moral dimension to the subject of eating disorders. She drew on the thought of another Catholic widely regarded as fat, St. Thomas Aquinas.

“He tended to think about morality in terms of habits,” Haile told OSV. For Aquinas, virtues and sins — temperance, prudence, gluttony, sloth — were all habitual behaviors that define a person over time and are difficult to change. “We might have these conversions of faith, these moments where we’re like, ‘I want to give my life to God. I want to recommit. I want to do God’s will’,” but the challenge then is cultivating new habitual behaviors based on this knowledge. And it’s here, she said, even secular experts recognize faith and hope as foundational for achieving lasting change of habits.

“We have to have faith in ourselves. And we have to have hope that there is something better for ourselves,” Haile said. “Faith, too, gives you a type of knowledge that transcends what we can have with a basic intellect.” That knowledge includes what faith tells us about the dignity of every person.

“So you don’t have that knowledge that God created all people beautiful, and you’re set, but that can motivate you to choose behaviors that will change your habits. And if you give it enough time, then your habits will change.”

Haile gave the examples of a person who strictly monitors her caloric intake at all times and a person who engages in cycles of extreme dieting followed by periods of binging on junk food.

“Neither one of those women actually thinks that they’re beautiful the way that God created them,” said Haile, whereas someone who’s heavier “might be the person who’s best able to do things that are conducive to their flourishing.”

Flourishing, Haile said, means making habits of behaviors that lend themselves to a person’s overall well-being. This involves all kinds of factors, which might not have much to do with someone’s weight.

“Maybe they’re thin, but they’re not ultimately at home in their body,” Haile said. “They don’t feel accepting of other people’s bodies. They’re really not flourishing. They’re not happy.”

Haile used the example of her own stress eating and how she stays thin only because of her need to exercise to cope with stress. People who compliment her thin appearance, she said, don’t see the full picture.

“You can’t judge people based on how they appear, and yet we do,” she said. “We’re entrenched in this view that thinness is a good and that we need to be thin to be beautiful. So even if you think that God made you beautiful as a big-busted, big-waisted woman, you’re still going to feel a twinge of guilt when you sit down to eat a cheesecake, because you know that this contributes to you not conforming to that model of thinness.”

The underlying injustice of conforming all bodies to a literally narrow model cuts across multiple areas, from the messages advertising pushes on girls in particular from a very early age to the experiences of women of color in society and even in the Church. And so much of those struggles resonate in a sentence that came to Amanda Martinez Beck in Eucharistic adoration:

“My body tells my story.”

It’s a line that Beck links to the wounds of the crucified Christ as well as to her own frame — size, stretch marks, scars and all.

“It has great value, for the sake of the kingdom” that we value weak bodies, broken bodies, marginalized bodies, “because they tell the story of the love of God.”

And God taking on a body is the ultimate body-positive act.

Father What-A-Waist

Father Ryan Rooney, administrator of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart Parish in Springfield, Massachusetts, has seen Catholic attitudes toward fat play out from his perspective among the clergy. Having struggled with his weight for most of his life, the stress of the first year following his 2011 ordination caused him to put on over 80 additional pounds in a span of about six months. He sought time away from ministry at the Guest House treatment center in Rochester, Minnesota.

“I initially struggled with going because I had so many things that were going on, and I wanted to do my own weight loss on my own time,” he told OSV, “but I needed to understand that I had a food addiction, and I needed to deal with some significant things that were underlying that food addiction.”

He lost 100 pounds in the five months he was away and has since lost another 150 pounds.

Today Father Rooney is not only a fraction of his former size, but also a spin instructor who encourages others to join him on a journey to better health.

Looking back, he is unsettled by what could be called clericalist tendencies that exacerbated his eating disorder.

The first: putting priests on a pedestal and not questioning their personal choices.

“Not to bother Father. We should be nice to him.” He has enough on his plate.

Another: the tendency to over-spiritualize the priesthood and not take into account the struggles of the whole human person, often bodily struggles.

Father Rooney found that this tendency also fed into attitudes Catholics have toward fatness among the clergy. A handsome young priest is jokingly called “Father What-a-waste,” i.e. he would have been such great marriage material. Or, as Father Rooney has also observed, the alternative:

“Let’s feed him well, so we don’t have to go there.”