“The world into which Jesus was born was harsh, cruel, violent, and unstable,” writes acclaimed British journalist and historian Paul Johnson at the beginning of his biography “Jesus.” Augustus Caesar (Ovtavian) had been named imperator (commander) by the Roman Senate in 27 B.C. During his rule, the spread of the empire vastly increased trade and Roman influence.

Virgil, Rome’s great poet, died just 15 years before Christ was born. Ovid, Livy and Seneca — all of whom were alive during Christ’s 33 years on earth — were bringing further glory to Rome’s poetry, philosophy and theater. This period of tremendous expansion meant that by the time of Christ’s birth, some 50-60 million people were governed under Roman rule, roughly one-third of whom were slaves.

With a historian’s precision, St. Luke records the time of Christ’s birth. The evangelist writes: “In those days a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be enrolled. This was the first enrollment, when Quirinius was governor of Syria” (Lk 2:1-2). The context of world history matters to Luke not merely as a detail of historical record; rather, it matters to the Christian understanding of the birth of Jesus.

Pope Benedict XVI notes in “Jesus of Nazareth”: “Only now, when there is a commonality of law and property on a large scale, and when a universal language has made it possible for a cultural community to trade in ideas and goods, only now can a message of universal salvation, a universal Saviour, enter the world: it is indeed the ‘fullness of time.'” The expansion of empire and the spread of Pax Romana, the peace of Rome, laid the foundation for a still greater king, a still greater peace.

We sing in the ancient carol: “Of the Father’s love begotten, / Ere the worlds began to be, / He is Alpha and Omega, / He the source, the ending He, / Of the things that are, that have been, / And that future years shall see, / Evermore and evermore.” The fabric of human history is redeemed by the designs of the eternal Word. In Jesus’ birth at Bethlehem 2,000 years ago, the uncreated Son entered into creation.

Time and eternity touch and mingle in the birth of Christ. Father Vincent McNabb says, “Eternity’s full tide overwhelms the banks of Time.” And while Christ enters definitely into time in the historical event of his birth, in the liturgy, we continue to enter into the time of Christ, the time of our redemption. Joseph Ratzinger puts it this way: “The liturgy is the means by which earthly time is inserted into the time of Jesus Christ and into its present.”

In the Eucharist, Jesus Christ is present to us in time, just as he was present to holy Mary and St. Joseph at the moment he was born. The same Christ, loved and worshipped by his Virgin Mother and her spouse, is given to us when we receive him in the Eucharist under the veil of bread and wine.

David’s royal city

Jesus Christ stooped to enter our time under the reign of empire, but was born in a particular place, conceding even to obey imperial decree. The lowliness of the Incarnation meant accepting the full plight of the age.

Luke tells us: “So all went to be enrolled, each to his own town. And Joseph too went up from Galilee from the town of Nazareth to Judea, to the city of David that is called Bethlehem, because he was of the house and family of David, to be enrolled with Mary, his betrothed, who was with child. While they were there, the time came for her to have her child” (Lk 2:3-6). And so it was that Jesus was born in Bethlehem, not Nazareth, apparently according to the dictates of Roman rule. By the designs of divine providence, the empire is placed at the service of salvation.

But the significance of Bethlehem not only underscores Jesus’ place as the heir of David (cf. 2 Sam 7:11-16) but also has a deeper meaning still. In Hebrew, Beth-lehem is two words and means “house” (Beth) and “bread” (lehem). Thus, St. Bede says, “The place he was born is rightly called ‘The House of Bread’ because he came down from heaven to earth to give us the food of heavenly life and to satisfy us with eternal sweetness.” Every place the Mass is offered is transformed into a sort of Bethlehem, a place where heaven touches earth, where Christ becomes our food. St. Ephraim the Syrian sings, “You are, O Church — the abiding Bethlehem — for in you is the Bread of Life!” It is just as Jesus told us: “I am the living bread that came down from heaven; whoever eats of this bread will live forever” (Jn 6:51).

In Arabic, moreover, the name of Bethlehem, Bayt Laḥm, literally means “house of meat.” St. Ignatius of Antioch wrote in one of his letters: “I have no taste for corruptible food nor for the pleasures of this life. I desire the bread of God, which is the flesh of Jesus Christ, who was of the seed of David; and for drink I desire his blood, which is love incorruptible.” The Eucharist is no mere bread; it is the very flesh of Christ, the meat of his sacred body. Jesus emphasizes this fact in St. John’s Gospel, saying, “For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink. Whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me and I in him” (Jn 6:55-6).

Because of the fertility of its soil, which in Biblical times produced an abundance of grain and produce, the region surrounding Bethlehem was called Ephrathah. Ephrathah means “fruitful, abundant.” This food, which is given to us in Bethlehem, is thus given to us in abundance. Recall that in the Old Testament Naomi and Ruth returned to Naomi’s home — Bethlehem — empty-handed. And there, God showered upon them many blessings. Similarly, the Eucharist offers unexpected, copious graces.

Had Jesus been born in a great city, men would have attributed his teaching or his success to his noble birth. But by being born in Bethlehem, he allows us to more easily discern that the power of God, rather than the power of men, is at work.

Laid in a manger

Not only is the time and place of Jesus’s birth significant, but it is also meaningful that Jesus was laid in a manger. As Luke’s Gospel states: “she gave birth to her firstborn son. She wrapped him in swaddling clothes and laid him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn” (Lk 2:7). Luke uses the word phatne, meaning feeding trough, three times in 10 verses. The emphasis and use of the relatively uncommon word underscore its significance.

The significance of the manger was not lost on the Fathers of the Church. St. Cyril of Alexandria says, “Whereas we were brutish in soul, by now approaching the manger, even His own table, we find no longer fodder, but the bread from heaven, which is the body of life.” Cyril recognizes how the Eucharist transforms us from the bestial state of life before Christ.

Similarly, St. Ambrose of Milan writes, “Finally, the spiritual donkey has not been nourished with feigned delights, but with a nourishment of a substantial nature, by the holy manger.” Like the theologian Origen and St. Jerome, Ambrose connects the manger in Luke to Isaiah 1:3: “An ox knows its owner, and an ass, its master’s manger [phatne]; But Israel does not know, my people has not understood.” As it was the case of old, there are many today who do not recognize Christ, the Eucharistic food, who was placed in the manger!

The first to adore Christ, lying in the manger, was the Virgin Mary. Her gaze must have been that of a loving mother, entranced by her infant child. Pope St. John Paul II writes, “Is not the enraptured gaze of Mary as she contemplated the face of the newborn Christ and cradled him in her arms that unparalleled model of love which should inspire us every time we receive Eucharistic communion?” It is the gaze we should foster whenever we are able to gaze upon Christ, present in the holy Eucharist.

Not only does the manger hold significance, but also the newborn Christ’s swaddling clothes are imbued with meaning. Jesus was born into the world as a baby, and the swaddling clothes show us that he was cared for like every other baby. They foreshadow Christ’s death, when he was wrapped in linen again and laid in a tomb. Thus the manger becomes a type of altar, bearing the body that will be given up for you. But with a little imagination, we can afford them a Eucharistic symbolism, too. As the swaddling clothes once wrapped the very flesh of God, so the veil of bread wraps the divinity we receive in the Eucharist.

The very Lamb of God

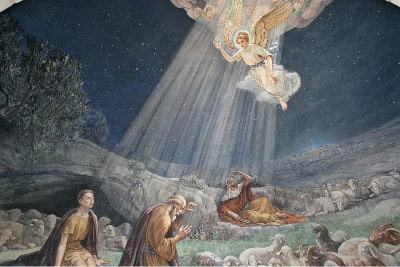

Much is rightly made of the presence of sheep and shepherds at the birth of Christ. Luke records: “Now there were shepherds in that region living in the fields and keeping the night watch over their flock. The angel of the Lord appeared to them and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were struck with great fear. The angel said to them, ‘Do not be afraid; for behold, I proclaim to you good news of great joy that will be for all the people. For today in the city of David a savior has been born for you who is Messiah and Lord. And this will be a sign for you: you will find an infant wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger'” (Lk 2:8-12). The shepherds have come to represent the especially beloved of God, the poor. In the monastic tradition, the shepherds came to exemplify watchfulness.

But most importantly, the shepherds stress that Christ is the heir of David. Recall that when Samuel sought David to be anointed king, David had to be fetched from the fields, where he was out tending the sheep. It is then that David is made king, the shepherd of Israel. And it is Christ who becomes David’s heir, the shepherd of all humanity.

But Christ is both shepherd and sheep. He is the lamb found among lambs. The fact that the sheep are the only animals mentioned in the Gospel narrative highlights their importance (ox and ass are included in our nativity scenes because of the verse from Isaiah mentioned above). It is the blood of the lamb that saves Israel at Passover (cf. Ex 12). When John the Baptist sees Christ he exclaims, “Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world” (Jn 1:29). Christ is our new Passover, the sacrifice offered once for all for the redemption of our sins. The Eucharist is that new Passover meal, the bloodless sacrifice that saves us from death.

In a Christmas homily a few years ago, Pope Francis relayed a delightful legend, which holds that when the shepherds came in search of the baby Jesus, they each brought a gift. Their gifts came from their poverty; most were hand-made and simple. But one shepherd stood apart, embarrassed, because he had nothing to give. Needing to free her hands to receive the gifts that were being presented, Mary asked the empty-handed shepherd to draw near. Into his empty hands she placed the child Jesus.

Reflecting on the legend, Pope Francis said: “That shepherd, in accepting him, became aware of having received what he did not deserve, of holding in his arms the greatest gift of all time. He looked at his hands, those hands that seemed to him always empty; they had become the cradle of God.” We receive the Eucharist in our poverty, in our emptiness. It is then that the Father desires to fill us, to allow us to cradle, to hold his Son.

Bread of the angels

The last sign of the nativity story that points to the Eucharist is the presence and song of the angels. The Gospel of Luke says: “And suddenly there was a multitude of the heavenly host with the angel, praising God and saying: ‘Glory to God in the highest and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests'” (Lk 2:13-14). While Octavian received the title “Augustus” (meaning, “worthy of adoration”) and left himself a monument dedicated to peace (the Ara Pacis Augusti), the angels sing the praise of God, who alone should be adored, and laud the peace the true Savior of the World brings. Luke is telling us that as great as Augustus is, the child born at Bethlehem is greater still.

So given that the rule of Caesar Augustus was marked by prosperity and security, it would be hard to imagine Christ not providing for his people. But unlike the Roman emperors who provided bread and grain, Christ offers his very self.

In the Old Testament, the manna God sent to sustain the Israelites is called “the bread of angels” (Ps 78:25, cf. Wis 16:20). In the Nativity story of the Gospels, the presence of the angels helps to highlight Christ, the true bread from heaven. We sing the Christmas hymn of the angels at every Sunday Mass, knowing that they accompany us in our work of praising God. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church says, “The Church joins with the angels to adore the thrice-holy God” (No. 335). With the spirit and joy of the angels then, we should sing in the presence of the Eucharist, “Gloria in excelsis Deo!”

Enter Bethlehem through the door of the Eucharist

Every Christmas is an invitation to return to Bethlehem. As we relive the beloved Christian story this year, discover anew the Eucharist, hidden at the beginning of the story of salvation. In the words of Pope Benedict XVI, “Dear friends, let us enter into the mystery of Christmas, now approaching, through the ‘door’ of the Eucharist; in the grotto of Bethlehem let us adore the Lord himself who, in the Sacrament of the Eucharist, desired to make himself our spiritual food to transform the world from within, starting with the human heart.”

Emmanuel means “God-with-us.” Our loving savior was born 2,000 years ago, in the littleness of Bethlehem. For us, he was wrapped in swaddling clothes and laid in a manger. Shepherds came before him in adoration and angels sang his praises. And all of this was done, knowing that he would remain with us, in that great gift of himself, the holy Eucharist.

Venerable Fulton J. Sheen said: “To each and everyone he [Christ] comes as if he had never come before in his own sweet way, he is the child who is born. He, Jesus the savior, he Emmanuel, he Christ at Christ’s Mass on Christmas.” Receive the Eucharist at Mass this Christmas and return again to Bethlehem, where the God of love first became present among men. Run to Bethlehem through the Eucharist.

Father Patrick Briscoe, OP, is editor of Our Sunday Visitor. Follow him on Twitter @PatrickMaryOP.

| MIDNIGHT MASS HOMILY BY POPE JOHN PAUL II |

|---|

“Adoro te devote, latens Deitas.” “Godhead here in hiding, whom I do adore.” On this night, the opening words of this celebrated Eucharistic hymn echo in my heart. These words accompany me daily in this year dedicated to the Eucharist. In the Son of the Virgin, “wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger” (Lk 2:12), we acknowledge and adore “the Bread which came down from heaven” (Jn 6:41, 51), the Redeemer who came among us in order to bring life to the world. Bethlehem! The city where Jesus was born in fulfillment of the Scriptures, in Hebrew means “house of bread.” It was there that the Messiah was to be born, the One who would say of himself: “I am the bread of life” (Jn 6:35, 48).

We adore you, Lord, truly present in the Sacrament of the Altar, the living Bread which gives life to humanity. We acknowledge you as our one God, a little Child lying helpless in the manger! “In the fullness of time, you became a man among men, to unite the end to the beginning, that is, man to God” (cf. Saint Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses, IV, 20, 4). You are born on this Night, our divine Redeemer, and, in our journey along the paths of time, you become for us the food of eternal life. Look upon us, eternal Son of God, who took flesh in the womb of the Virgin Mary! All humanity, with its burden of trials and troubles, stands in need of you. Stay with us, living Bread which came down from heaven for our salvation! Stay with us forever! Amen! — Pope St. John Paul II, homily for Midnight Mass (2004) |

In Bethlehem was born the One who, under the sign of broken bread, would leave us the memorial of his Pasch. On this Holy Night, adoration of the Child Jesus becomes Eucharistic adoration.

In Bethlehem was born the One who, under the sign of broken bread, would leave us the memorial of his Pasch. On this Holy Night, adoration of the Child Jesus becomes Eucharistic adoration.