Pope Benedict XVI spoke often of our beliefs becoming ossified, turning into stone, no longer living. The Catholic novelist Walker Percy similarly saw that, in the modern world, words are often deprived of their meanings. When the phrases in which we profess our faith become just words, when they no longer have life within them, how do we recapture their meaning so that they can move us once more?

These thoughts were far from my mind as I knelt in a pew in St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rockford, Illinois, a decade or so ago, completing the penance assigned by my confessor, reciting the Lord’s Prayer with my eyes fixed on the crucifix at the front of the church. But I have pondered them often in the years since, because that priest, in giving me that particular penance that day, stirred something within me that I can only describe with the Greek word anamnesis, the act of memory, central to the Christian liturgy, that makes what we remember truly present for us again.

Give us this day

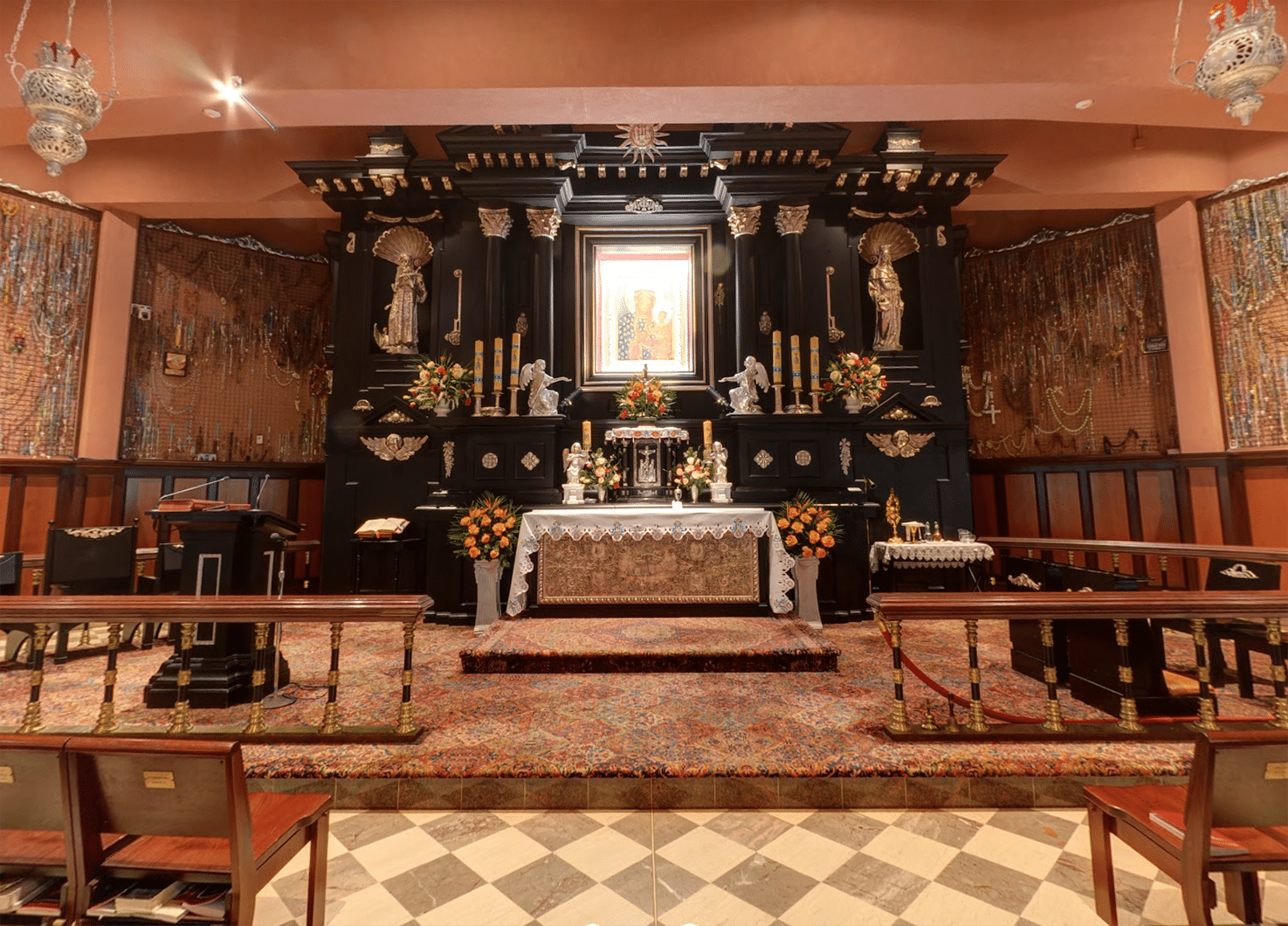

Give us this day … When Jesus taught his disciples how to pray, he knew how he would die. And he knew that, before he did so, he would leave them with a perpetual gift, the sacrament of his body and blood, to be offered on the altar before me and on altars all around the world every day until the end of time, and that on those altars his sacrifice on the cross would become present once again. Through the Eucharist, that sacrifice never ends. For us, every day is the evening of Holy Thursday, the afternoon of Good Friday; the world is continually redeemed this day by his sacrifice re-presented on this altar.

Our daily bread

… our daily bread … “[A]nd the bread that I will give is my flesh for the life of the world” (Jn 6:51). You may have heard a homily in which a priest explained that the word which we normally translate here as “daily” also means something like “supersubstantial,” the bread beyond all other breads, which is certainly a fitting description of the Eucharist. But there’s a deep truth to be found in the ordinary translation as well. We are nourished every day by Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, through which he makes all things new. Whether we receive the Eucharist daily or not, Christ’s sacramental sacrifice is truly our daily bread. To keep that sacrifice before our eyes, to mark it on our body when we make the Sign of the Cross, to unite ourselves to it by, in the words of Walker Percy, “eating Christ himself to make me mortal man again and let me inhabit my own flesh” — these are the acts that sustain us on our pilgrimage through this life. The Eucharist is truly viaticum — food for the way — and not just at the end of our lives.

Forgive us our trespasses

… and forgive us our trespasses … As I said each of those words slowly while looking at the crucifix, I recognized that my trespasses — my sins — are what put Christ on that cross. God forgave me at the cost of the life of his own Son, the same Son who gave us the memorial of that sacrifice as our daily bread. This is what true forgiveness looks like, which is something we must always keep in mind as we continue to pray: … as we forgive those who trespass against us …

“Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy” (Mt 5:7). We think of mercy most often as something God grants us, not something we give, but the mercy and forgiveness we receive both flow from and demand the mercy and forgiveness we show to others. And mercy and forgiveness come with a cost. Are we willing to lay down our lives, to unite ourselves to Christ’s sacrifice, in order to forgive those who trespass against us? If not, what do we think we are doing when we receive his Body and Blood, offered to God the Father as the supreme act of mercy and forgiveness?

Lead us not into temptation

… and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. This is the ultimate temptation, the greatest evil: to consume the body and blood of Christ as cheap grace, not recognizing his sacrifice or acknowledging that it must call forth our own. Because this is the heart of the sacred mysteries we celebrate in the Mass, presented to us on the crucifix and summed up in the Lord’s Prayer: to rise with Christ, we must first die with Christ. Unless those words have life within them, we shall not have life within us.