VATICAN CITY (CNS) — The reason why the 2024 edition of the Vatican yearbook has re-inserted “Patriarch of the West” as one of the historical titles of the pope appears to be a response to concerns expressed by Orthodox leaders and theologians.

For months after the yearbook, the Annuario Pontificio, was released, the Vatican press office said it had no explanation for the reappearance of the title, which Pope Benedict XVI had dropped in 2006.

But new documents from the Dicastery for Promoting Christian Unity place the change squarely in the middle of a broad discussion among all mainline Christian churches on the papacy and the potential role of the bishop of Rome in a more united Christian community.

Members of the dicastery proposed that “a clearer distinction be made between the different responsibilities of the Pope, especially between his ministry as head of the Catholic Church and his ministry of unity among all Christians, or more specifically between his patriarchal ministry in the Latin Church and his primatial ministry in the communion of Churches.”

Reactions from Orthodox leaders

For the Orthodox, the papal title of “Patriarch of the West” is an acknowledgement that his direct jurisdiction does not extend to their traditional territories in the East.

Armenian Orthodox Archbishop Khajag Barsamian, the representative of the Armenian Apostolic Church to the Holy See, told reporters June 13, “The recent reinstatement of the title of ‘Patriarch of the West’ among the pope’s historical titles is important, since this title, inherited from the first millennium, evidences his brotherhood with the other patriarchs.”

Cardinal Kurt Koch, prefect of the Dicastery for Promoting Christian Unity, said that “when Pope Benedict XVI canceled this title and when Pope Francis introduced it again, they did comment” on why they made the decision. “But I am convinced they did not want to do something against anyone, but both wanted to do something ecumenically respectful.”

Historical efforts toward ecumenical reflection

Twenty-nine years ago, St. John Paul II called for an ecumenical reflection on how the pope as bishop of Rome could exercise his ministry “as a service of love recognized by all concerned.”

Already in 1967 St. Paul VI had recognized that the papacy was “undoubtedly the gravest obstacle on the path of ecumenism.”

Following St. John Paul’s ecumenical invitation in 1995, studies were conducted, meetings were held and reports were made.

The pace picked up with the pontificate of Pope Francis and his frequent references to being the bishop of Rome, his reliance on an international Council of Cardinals to advise him on issues of governance and his continuing efforts to reform and expand the Synod of Bishops and the practice of “synodality.”

Over the past three decades, the Catholic Church’s ecumenical partners responded to St. John Paul’s request by questioning things like papal infallibility and claims of universal jurisdiction, yet many also expressed support for trying to find an acceptable way for the bishop of Rome to serve as a point of unity for all Christians.

According to members of the Dicastery for Promoting Christian Unity, there has been “a significant and growing theological convergence” both on the need for a universal figure at the service of Christian unity as well as for Christian churches and communities, including the Catholic Church, to learn from each other’s styles and structures for consultation, governance and leadership.

Study document on papal primacy and synodality

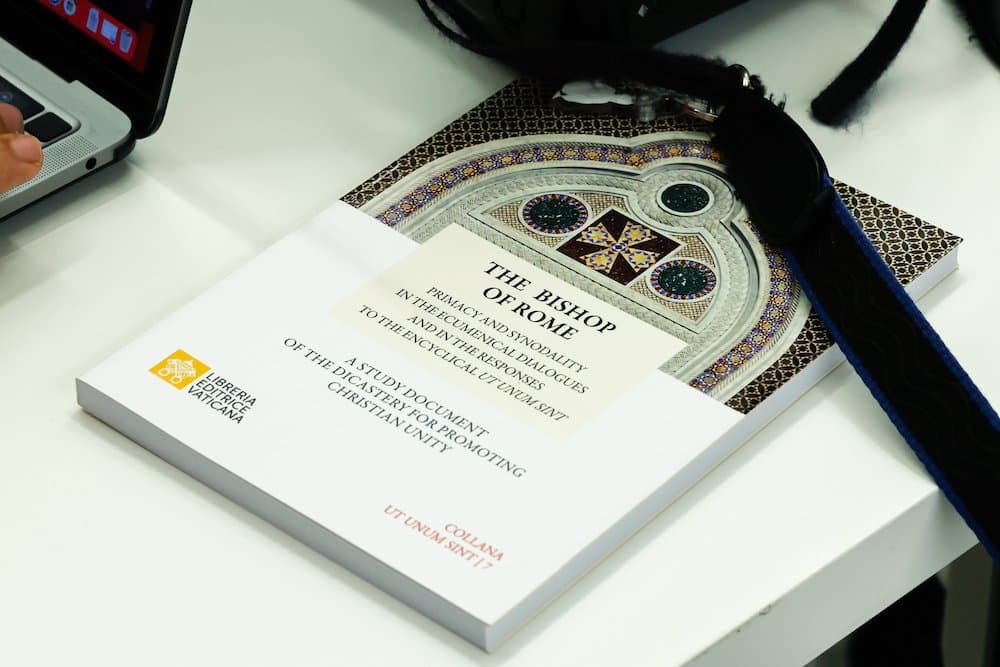

Staff of the dicastery have spent years summarizing the reflections and released their work June 13 as a “study document” titled, “The Bishop of Rome. Primacy and Synodality in the Ecumenical Dialogues and in the Responses to the Encyclical ‘Ut unum sint.'” The publication also included a series of proposals titled, “Towards an Exercise of Primacy in the 21st Century,” which was approved in 2021 by the cardinals and bishops who are members of the dicastery.

Swiss Cardinal Kurt Koch, prefect of the dicastery, wrote in the preface to the study document that Pope Francis approved its publication.

The role a pope could play in a re-united Christian church obviously involves practical considerations about power and authority and how they are exercised. But for the ecumenical dialogues, the first considerations are tradition — what was the role of the bishop of Rome in the early centuries before Christianity split — and theological, including what is the church and how is it different from other kinds of organizations.

The document approved by dicastery members said the dialogues have “enabled a deeper analysis of some essential ecclesiological themes such as: the existence and interdependence of primacy and synodality at each level of the Church; the understanding of synodality as a fundamental quality of the whole Church, including the active participation of all the faithful; and the distinction between and interrelatedness of collegiality and synodality,” that is, between the shared responsibility of bishops and the shared responsibility of all the baptized.

Papal infallibility and ecumenical challenges

One crucial issue for many Christians is papal infallibility; in fact, “infallibility” is cited 56 times in the documents released June 13.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church says, “Christ endowed the Church’s shepherds with the charism of infallibility in matters of faith and morals. The exercise of this charism takes several forms: The Roman Pontiff, head of the college of bishops, enjoys this infallibility in virtue of his office, when, as supreme pastor and teacher of all the faithful — who confirms his brethren in the faith — he proclaims by a definitive act a doctrine pertaining to faith or morals.”

Catholic and other theologians and bishops, the new documents said, have called for “a Catholic ‘re-reception,’ ‘re-interpretation,’ ‘official interpretation,’ ‘updated commentary’ or even ‘rewording’ of the teachings of Vatican I,” the council held in 1869-70 that solemnly proclaimed papal infallibility under some circumstances.

Emphasizing those limited circumstances does not seem to suffice. For example, the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission in 1981 said, “The ascription to the bishop of Rome of infallibility under certain conditions has tended to lend exaggerated importance to all his statements.”

One thing everyone involved in ecumenical dialogue agrees on, though, is that the unity of the early Christian communities was expressed by their leaders and members visiting one another, praying together and working together. The new documents called for those efforts to continue and to grow.