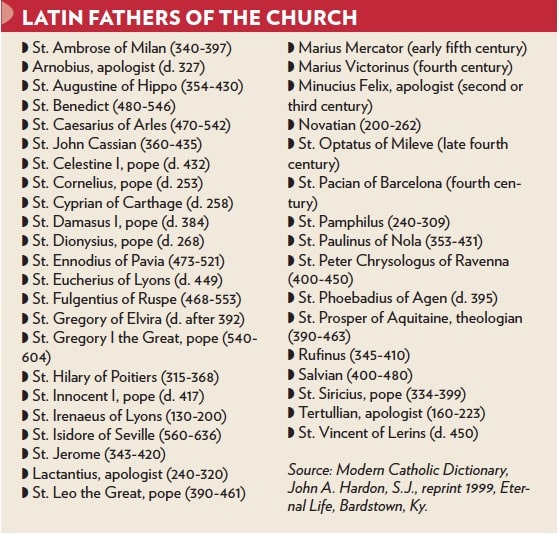

A previous In Focus explored some of the great Fathers of the Eastern, or Greek, Church. This week the Latin (Western) Fathers are highlighted. While there is no official list of the Fathers, since the fifth century the criteria for selection has been that the individuals lived holy lives, were orthodox in their teachings and writings, lived during antiquity (the first through seventh centuries) and have been approved by the Church. According to some historians, there are more than 100 total Church Fathers (East and West); many of the same names are found on the different lists.

The Fathers helped define, establish and promote the dogmas of the Catholic faith. They not only explained and advanced Christianity, but they stood against those who would defame, deny or exploit our Lord, Jesus Christ. This author is not able to adequately measure or describe the sanctity of these men, who were popes, bishops, theologians, apologists and writers. Some are saints, and all gave themselves in the service of the Lord. Here are a handful among the giants from the Western Church who have the title Church Father. They are categorized by those who lived just before the Council of Nicea, those in the era of Nicea and those after the council, up through the seventh century.

Part one about the Greek (Eastern) Church Fathers was published Jan. 21 and can be found at: bit.ly/fatherspart1.

Ante-Nicea Fathers

Tertullian (c. 155-220)

The Fathers of the Western Church begin with Tertullian in the second century. Although not a saint, he was the most prominent Western theologian in the era before the Council of Nicea in A.D. 325. A well-known lawyer, Tertullian converted to Christianity around 197; he studied the early Fathers of the East and brought their thought into the Western Church. He was the first among all the Fathers to use Latin in his writings. Some historians say he was a priest, but there is little evidence to that end.

As a layman, he instructed those seeking to be baptized and wrote pieces called “On Baptism” and “On Repentance” in the years between A.D. 200 and 206. These were the first written works dedicated to Church sacraments. In “On Repentance,” he writes that repentance should never be necessary after baptism, advising not to abuse God’s mercy: “[The devil’s] poisons are foreseen by God; and although the gate of repentance has already been closed and barred by baptism, still, he [God] permits it to stand open a little. In the vestibule he has stationed a second repentance, which he makes available to those who knock — but only once, because it is already the second time, and never more, because further were in vain.”

Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus, his full name, was quick to address the Roman persecutions, and he challenged the Roman judicial practices instituted against the Christians in the second and third centuries. He wrote in his most famous piece, “The Apology”: “Crucify us, torture us, condemn us, destroy us! Your wickedness is proof of our innocence, for which reason does God suffer us to suffer this. When recently you condemned a Christian maiden to a panderer, rather than to a panther, you realized and confessed openly that with us a stain on our purity is regarded as more dreadful than any punishment and worse than death. Nor does your cruelty, however exquisite, accomplish anything: Rather, it is an enticement to our religion. The more we are hewn down by you, the more numerous do we become. The blood of martyrs is the seed of Christians!”

He argued in the same piece that Christians were called criminals, accused of every calamity, ultimately, because they were Christians and not because they had been proven guilty of anything: “They consider the Christians to be the cause of every public disaster and of every misfortune which has befallen the people from the earliest times. If the Tiber rises to the city walls, if the Nile does not rise to the fields, if the weather continues without change, if there is an earthquake, if a famine, if pestilence, immediately, ‘Christians to the lions.'” His defense of Christianity was brilliant. Like St. Justin, the Greek Father of the same era, Tertullian clearly identified the many Roman absurdities in regard to Christians. Such work had little impact on the treatment of Christians until some 200 years later.

Although a great apologist for Christianity, he became a sympathizer of the Montanism movement. This heresy surfaced in the second century, advocating the near-term end of the world and, as such, encouraged continuous fasting, living in poverty, the denial of second marriages and encouraged martyrdom. Their leader, Montanus, and other followers claimed to speak for the Holy Spirit and even predicted the time of the second coming of Christ. As everyone was considered a priest, there was thus no need for ordained clergy. Tertullian joined this group in the early third century and sought to advance their beliefs. The Church condemned Montanism and excluded them from receiving holy Communion. Despite his allegiance to this heretical group, Tertullian’s early commitment and constant work to defend and advance Christianity against her enemies marked him as the first of the Western Fathers.

St. Irenaeus (d. 202)

Irenaeus is credited with putting together the beginnings of what eventually would become the New Testament, combining the Gospels and the authentic teachings and writings of the apostles, and setting apart these sacred Christian Scriptures as equal to the Old Testament. He witnessed to the Apostolic teachings in his works against heresies and especially refuted the false teachings of Gnosticism. This heresy was made up of so-called Christians who separated the world into good and evil – spiritual things were good, but material things, including the human body, were bad. They believed that Jesus only appeared to be human, was not true God, and that a select few of them had been given a special knowledge coming directly from the apostles, and only those with such knowledge could attain salvation. Irenaeus’ explanations of the fundamental Christian beliefs not only rejected the Gnostics, but promoted the concept of apostolic succession — that the original followers of Christ handed down to Church bishops and priests the basic and true teachings to which all Christians should adhere: “The tradition of the apostles, manifested throughout the world, can be clearly seen in every church by those who wish to behold the truth. We can enumerate those who were established by the apostles as bishops in the churches, and their successors down to our time. … They certainly wished those whom they were leaving as their successors, handing over to them their own teaching position, to be perfect and irreproachable” (“Against Heresies”). Irenaeus exposed Gnosticism and its many false teachings as being with no foundation in the Christian doctrine taught by the apostles.

In the same writing, endowed with a wisdom that only can come from the Holy Spirit, and like those before and after, he clearly and succinctly reflects on the unity of the Church, how the Church “although scattered throughout the world … proclaims [the doctrine], teaches them, and hands them down, with perfect harmony, as if she passed through only one mouth.”

He often is referred to as the Father of Theology and was a student or acquaintance of the great St. Polycarp of Smyrna. Irenaeus wrote a kind of catechism called “Demonstration on the Apostolic Preaching” in which he offers his thoughts on attaining salvation, concluding that man must stay true to his faith, not allow material possessions take him off the right path: “For what profit is it to know the truth in words, and to pollute the flesh and perform the works of evil? Or what profit can purity of the flesh bring, if truth be not in the soul?” Proposed as a Doctor of the Church, bishop, theologian, the first of the Church Fathers to allude to Mary as the New Eve – Irenaeus was essential in the development of our Catholic faith.

Nicea Fathers

St. Ambrose (340-397)

St. Ambrose was the first of the Church Fathers to recognize that the Roman emperors were more and more imposing themselves on Christianity, seeking to gain control of the Church. Ambrose argued that in Church matters, it was not the emperor who ruled the Church but the bishops. He was a holy man of action and opposed anyone who sought to vilify Christianity or made false accusations against the Church.

Serving as the governor of Northern Italy, he was not yet baptized when elected by the people of Milan as their bishop to replace Bishop Auxentius, who was an Arian. He didn’t want the job, but the position was thrust on him by his emperor. After being baptized, he became bishop of Milan in 374 and remained as such until he died in 397. He did not teach or write thoughts that were necessarily original, but he expounded on and affirmed the teachings of Jesus, the apostles and the Fathers. Ambrose admired the works of Origen and used and promoted the Scripture analysis of Origen into the Western Church.

Influential and highly esteemed, he did not hesitate to take on the emperor when he thought necessary. In 388, Emperor Theodosius I (r. 347-395), during a fit of anger, murdered 7,000 Christians. In response, Ambrose refused to give the emperor holy Communion until after Theodosius made a public penance. This is considered a major turning point in the role of the bishop over the emperor, the Church over the state in religious issues. On another occasion, Emperor Valentinian II (r. 375-392) supported his mother’s attempt to use a church in Milan for Arian celebrations; Ambrose courageously and successfully resisted. In a homily, he responded to the emperor: “The tribute that belongs to Caesar is not to be denied. The Church, however, is God’s, and it must not be pledged to Caesar; for God’s temple cannot be a right of Caesar. … For the emperor is in the Church not over the Church; and far from refusing the Church’s help, a good emperor seeks it” (“Sermon Against Auxentius”).

Ambrose excelled as a teaching bishop, emphasizing the virtues of a Christian life as well as explaining the Scriptures. He wrote hymns and was the first bishop to introduce the singing of hymns into Church congregations. In Italy of the fourth century, the liturgy differed somewhat between churches. Milan was similar to Rome, but there were local variations. When Monica, Augustine’s mother, asked Ambrose about the differences, he replied that “when in Milan she should follow the Milanese ways, and in Rome should do as Rome did.”

Every Dec. 7, the Church honors Ambrose with an obligatory memorial; the prayer over the offerings reads, “As we celebrate the divine mysteries, O Lord, we pray, may the Holy Spirit fill us with the light of faith by which he constantly enlightened St. Ambrose for the spreading of your glory.” Ambrose is both a Father and one of the first four Doctors of the Church.

St. Jerome (c. 340-420)

St. Jerome was born Eusebius Hieronymus and is known to most every Catholic as the person who translated the holy Scriptures from the Hebrew and Aramaic languages into Latin and into what we call the Vulgate (common or popular) Bible. This Bible has been used in the Church since the fifth century. Twelve centuries later, Church bishops, during the fourth session of the Ecumenical Council at Trent, declared that the Vulgate Bible “has been approved by the Church, be in public lectures, disputations, sermons and expositions, be held as authentic: and no one is to dare, or presume to reject it under any pretext whatever.”

Over the centuries, the Vulgate has been revised, but Jerome’s work still is considered the official Bible text of the Catholic Church. As secretary to Pope Damasus (r. 366-384), Jerome was commissioned to translate the Bible, and it took him in excess of 22 years to complete — the great literary achievement of the fourth century and one that continues to impact our world even today.

An opponent of Arianism, Jerome wrote “The Dialogue Against the Luciferians,” which identified the chaos this heresy was causing the Church: “The whole world groaned when, to its astonishment, it discovered that it was Arian. … The little ship of the apostles was in peril, driven by the winds and with her sides buffeted by the waves. There was now no hope. But the Lord awoke, he commanded the storm, the beast died, and there was calm once again.”

Jerome was a priest, a great writer, a Doctor and Father of the Church, and a saint, but history indicates he was not necessarily a nice person. He was outspoken and a name-caller, naming some bishops Satan; he called Ambrose a deformed cow.

The sharp tongue of Jerome is found in his letter “Against Helvidius: The Perpetual Virginity of Blessed Mary.” Helvidius, a disciple of Arianism, denied the perpetual virginity of the Blessed Mother. Jerome rejected this belief: “You [Helvidius] say that Mary did not remain a virgin. As for myself, I claim that Joseph himself was a virgin, through Mary, so that a Virgin Son might be born of virginal wedlock.” Then Jerome, anticipating the kind of reply he would receive, added: “And since I know that you, having been bested by the truth, will retort to disparagement of my life and to bad-mouthing my character — little ladies generally act in this fashion; and, when their masters have bested them, they sit in the corner and wish them evil — I only tell you in advance that your railings will redound on my glory, when you lacerate me with the same mouth you used in your detraction of Mary. The Lord’s servant and the Lord’s Mother will have each an equal portion of your canine eloquence.”

Jerome has been described as a great rather than a good man. No matter the fault-finding, he changed the world.

It is difficult for us today, with all our marvels of technology, to imagine the effort and dedication, the enormity of the task it took to translate the sacred Scriptures from Hebrew and Aramaic into Latin, into the Bible we have today. This work garnered him the title Doctor of the Church. He wrote in his commentary on Isaiah: “To be ignorant of the Scriptures is to be ignorant of Christ.”

Post-Nicea Fathers

St. Augustine (354-430)

In Pope Benedict XVI’s book “Holiness is Always in Season,” Benedict wrote of Augustine, “A civilization has seldom encountered such a great spirit who was able to assimilate Christianity’s values and exalt its intrinsic wealth, inventing ideas and forms that were to nourish the future generations, as Paul VI also stressed: ‘It may be said that all the thought-currents of the past meet in his works and form the source which provides the whole doctrinal tradition of succeeding ages.'” No Father or Doctor of the Church has had more impact on Christianity than Augustine. A natural writer, it is estimated that he wrote more than 6 million words.

Certainly he did not start as a saint or even a Christian. For the first 33 years of his life, he seemed to have no direction: “I ran headlong with such great blindness that I was ashamed to be remiss in vice in the midst of my comrades. For I heard them boast of their disgraceful acts and glory in them all the more, the more debased they were. There was pleasure in doing this, not only for the pleasure of the act, but also for the praise it brought” (“Confessions,” 2.3).

Augustine had a long affair with a woman, and they had a child out of wedlock. Born in North Africa, he traveled to Milan by way of Carthage and Rome. His mother, St. Monica, who was a devoted Christian, followed him, praying he would find the God she served. In Milan, he heard the homilies of St. Ambrose, and through the words of Ambrose he began for the first time to understand the Scriptures. He was baptized by Ambrose on Easter in 387.

Returning to North Africa, he consumed himself with the study of Scriptures, gathering others to hear his thoughts. Those who knew him encouraged his ordination, and eventually he was elected as bishop of Hippo, in present-day Algeria. He was an excellent shepherd of his flock, and his homilies are still imitated. These were uneducated people he spoke to, and this brilliant man and eloquent speaker explained the Christian faith in a way they understood.

It was in this era that he began to write, expressing himself with passion and clarity. Unlike some of the other imminent Church Fathers, he was an original thinker and has been referred to as a genius.

In his lifetime, Augustine was confronted with numerous heresies attacking Christianity and the Church. Priscillianists denied the preexistence of Jesus and his humanity; the Donatists claimed the sacraments were not valid if administered by an unworthy priest; the Pelagians believed that a person could earn salvation without God’s grace. Augustine logically rejected all these heretical beliefs in such a way they were condemned or suppressed by the Church. Through his writing he excelled in explaining original sin, predestination, grace, atonement and vast other Christian beliefs and doctrines.

As a youth, and before being baptized, Augustine joined the Manichaeisms, who professed that there were two gods — one of good and spirit, one of darkness, evil and matter. The good and evil were always in conflict. They condemned the Old Testament and claimed that all material things were immoral, contaminated while spiritual things were pure, without flaw. Augustine eventually would dismiss these beliefs and conclude that there is only one God, and he become a fervent student of the Old Testament.

Gregory the Great (540-604)

Raised in a wealthy Roman family and heir to a fortune, Gregory had every advantage — then he gave it all away. Around 575, he contributed all his possessions to the poor, turned his home into the monastery of St. Andrew, became a monk and lived in total austerity. He claimed this was the happiest time of this life, until 579, when he was called by Pope Pelagus II (r. 579-590) to serve as the papal ambassador to Constantinople.

When Pelagus died, the people along with the clergy in Rome selected Gregory to be the pope. He tried to avoid the duty, but in A.D. 590 he was consecrated as the Roman pontiff. In a job he didn’t want, he excelled in keeping the Church unified and strengthened the foundation for the future of the papacy, instituted reforms among the clergy, ended concubinage and simony, and was the catalyst to keep Italy from total political and economic collapse during the invasion of the Lombards. Among all the Roman pontiffs, Gregory is considered the model administrator. His never-ending efforts to help the poor have long been admired; he was the first pope to call himself, “The servant of the servants of God.”

He worked continuously to expand Christianity to all of Europe and converted the king and queen of the Lombards when they invaded Italy. He was ever aware of the Fathers who had come before him and the impact on Christianity resulting from their efforts at the great ecumenical councils. Regarding the first four councils (Nicaea, Constantinople I, Ephesus and Chalcedon), he said: “I confess that I revere, like the books of the holy Gospel, [those] four councils. … But all persons that the aforesaid councils reject, I reject; those whom they venerate, I embrace; because, since those councils were shaped by universal consent, anyone who presumes either to loose whom they bind or bind whom they loose overthrows not them but himself. Whoever, therefore, deems otherwise, let him be anathema” (Letter of Pope Gregory I to John, Patriarch of Constantinople).

His work entitled “Dialogues” is simply written, easy to understand and has long been popular among Christians. For example, he is asked if in hell there are different fires for different sinners. Gregory wrote: “Certainly the fire of hell is one; but it does not torment all sinners in the same way. For there each sinner feels its punishment according to his own degree of guilt. … But it remains unquestionably true that there is no end of joy for the good, so too there will be no end of torment for the wicked.”

He is a saint, pope, Father and Doctor of the Church, and assigned the title “Great.” Analyzing the time in which he lived, it was Gregory who was at the forefront of transitioning the world into the middle ages.

D.D. Emmons writes from Pennsylvania.