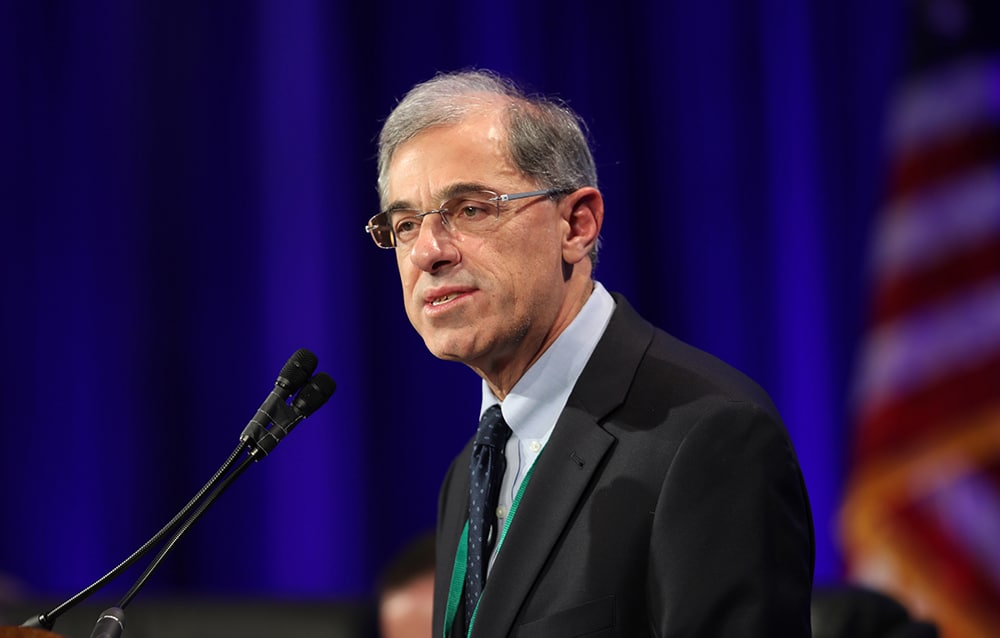

After eight years as chairman of the National Review Board, a lay committee that advises the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops on addressing clergy sex abuse, Francesco C. Cesareo says the Catholic Church in the United States has made “some progress, but a mixed progress.”

“There’s still some work to be done going forward in order to tighten up the charter and the processes that are part of it,” Cesareo said in reference to the U.S. bishops’ 2002 Dallas Charter that instituted new norms to investigate clergy sex abuse cases.

During his two consecutive four-year terms as chairman of the National Review Board, which ended in June, Cesareo often pushed to amend the charter, to make it less vague and more responsive to new information. He advocated for the laity to have a greater role in keeping clergy accountable and lobbied for a more independent annual auditing system to monitor how dioceses and Church institutions are complying with the charter.

In a recent interview with Our Sunday Visitor, Cesareo, who is the president of Assumption College in Worcester, Massachusetts, reflected on his tenure as the NRB chairman, the progress that has been made in responding to the sex abuse scandals, the challenges that remain and what he believes bishops need to do to rebuild trust in the Church.

Our Sunday Visitor: On clergy sex abuse and accountability, where do you think we are now compared to where we were eight years ago?

Francesco C. Cesareo: I think that there’s been progress in terms of really understanding that this issue of clerical sexual abuse has to be at the forefront of the work of the bishops, that they cannot assume it is a historical event that is done with and occurred in the past.

I think a lot of the focus has been on dealing with the implementation of various aspects of the charter in a more substantive way — for example, the establishment of diocesan review boards and safe environment programs and making sure those are operational in dioceses across the country.

Having said that, the charter still remains a document that leaves a lot of room for interpretation. What the National Review Board really tried to do during my eight years was to tighten up the charter, make it less gray, less ambiguous. I don’t think we were able to succeed as much as we would have liked to have succeeded in that area.

While we’ve seen more dioceses begin to audit their parishes, which is very important, the fact that we were not able to get that as a requirement in the charter was disappointing. That’s something the NRB has continuously pushed forward each year. Until bishops know what’s going on at the parish level, it’s very hard for them to know for certain whether a culture of safety has actually been integrated into the life of their dioceses.

We also saw some changes to the audit instrument that improved it, but not to the extent that the National Review Board was looking for. The National Review Board has really been pushing for a much more substantive audit instrument and a more independent audit process. That’s an area that still needs to be worked on by the National Review Board moving forward.

Our Sunday Visitor: Where is the Church now in terms of holding bishops accountable?

Cesareo: Up until the McCarrick situation, bishops were not really held accountable. It was that situation that brought the issue to the forefront. While there’s been progress with Vos Estis, what the National Review Board was looking for was a greater role for the laity in the process of holding bishops accountable. We were not supportive of the metropolitan model that was actually adopted, because we felt that model has the potential of having too many cracks or loopholes that would not be sufficient in addressing bishops’ accountability.

The establishment of a lay commission that would oversee any allegations made against a bishop was not part of the third-party reporting system that the bishops ultimately approved going forward. While the laity can be engaged in the process if the metropolitan invites them to, they’re not taking the lead. The National Review Board had concerns about that.

Our Sunday Visitor: The most recent audit for the bishops’ conference indicated that the number of clergy sex abuse allegations more than quadrupled in 2019 compared to previous years. What do you make of that?

Cesareo: I think the problem is the charter, or the audit, is seen as a checklist. So if I’ve done this, check it off. If I’ve done that, check it off. We haven’t been able to really develop a mindset that the checklist approach doesn’t guarantee a culture of safety. What we have to do is get people on the local level to recognize that if there is not an openness to the kind of change that we need to see on the parish level, it’s going to be difficult to really develop and ensure that a culture of safety is rooted in the life of that community.

Our Sunday Visitor: Does the audit say anything about the reliability of the reporting in previous years?

Cesareo: Whenever there is a major [clergy sex abuse] story that hits nationally, that often leads to increased numbers of victims and survivors to come forward. It brings to the forefront what (survivors) have experienced, and they feel at that point that they can come forward. We often see these kinds of spikes when major issues emerge on the national level.

Also, the heightened scrutiny by district attorneys across the country has led more victim-survivors to come forward and to feel that they can tell their experiences. I think we also have to take into account delayed reporting, in which we know that every person who has been victimized and has survived is able to verbalize what they experienced in different ways and at different times. Delayed disclosures are not unusual.

But I think what’s interesting is that the curve hasn’t changed. What we see is that in that period of time, you still have a spike [in abuse cases], which keeps moving forward, but we don’t see increases in allegations in the post-charter years moving up in that same way. What I think that speaks to is the fact that the Church’s response since 2002 has been effective, and the fact that the vast majority of these allegations are historical allegations speak to the Church’s lack of response in the past as opposed to the Church’s response since 2002.

However, I think it was troubling that we saw a spike of allegations by current minors in this audit year, more so than in the most recent past. I think that’s something that has to be looked at carefully and closely to try to understand what might be going on there so that we don’t see another period of time where the Church experiences what it did prior to 2002.

Our Sunday Visitor: What are some concrete changes you would like to see to the Charter?

Cesareo: One example: The Charter says diocesan review boards are to meet regularly. We wanted to make that very specific and say minimally once a year because “regularly” is up to interpretation. What does regularly mean? Does it mean only when allegations come forward in a diocese? Does it mean twice a year? Once a month? Once a quarter? It varies. …

Another thing we wanted to get into the charter was mandatory parish audits, which we didn’t get. We also said that all allegations should be sent to the diocesan review board so that the diocesan review board can better advise the bishop and there would be no gate-keeper which could potentially lead to problems.

Our Sunday Visitor: Moving forward, what do bishops need to keep in mind to maintain progress on this issue?

Cesareo: The bishops have to understand that the charter is a living document, which needs to adapt and to change based on what we’ve learned in the last 20 years. I think there’s been a hesitancy to do that. For example, there is no mention of boundary violations in the charter, because in 2002, boundary violations were not an issue. But we’ve seen boundary violations becoming more of an issue, and now we know that boundary violations can often be a red flag. The charter should reflect how you deal with boundary violations. But there’s been a resistance to include that in, because the charter is often seen as a static document as opposed to a living document that needs to reflect what we’ve learned over the last 20 years.

If we make a change to the charter or if we add something to the charter, it doesn’t mean that we are pointing fingers at the bishops. What it means is we’ve learned something we didn’t know before that needs to now be incorporated in this document so as to ensure that this does not become a problem. That’s something that needs to be better understood. The charter does need to be changed, it does need to be revised, because we learn, and as we learn, we try to do things differently and better. That’s not an indictment of things we’ve done in the past. It’s an acknowledgement that we have to do more because of what we’ve experienced and what we’ve learned.

Brian Fraga is a contributing editor for Our Sunday Visitor.