“From the Chapel” is a series of short, daily reflections on life and faith in a time of uncertainty. As people across the world cope with the effects of the coronavirus — including the social isolation necessary to combat its spread — these reflections remind us of the hope that lies at the heart of the Gospel.

“From the Chapel” is a series of short, daily reflections on life and faith in a time of uncertainty. As people across the world cope with the effects of the coronavirus — including the social isolation necessary to combat its spread — these reflections remind us of the hope that lies at the heart of the Gospel.

Growing up in Michigan, just a mile or so inland from the shore of Lake Michigan, Easter, even when it came early, was always heralded by signs of spring. Here in Huntington, Indiana, on the Monday of Holy Week in April 2020, the crocuses have come and (mostly) gone, the grape hyacinths are up, and the daffodils are in full bloom.

But what I really look forward to seeing are the forsythia. I can’t say why those cascading branches of yellow, with the flowers appearing before the leaves, appeal so strongly to me, but they have ever since I was young. My parents had a forsythia bush in the backyard, and my grandparents had a huge cluster, several feet across and taller than any of us, down the hill by the first pond. For a few years in graduate school in Washington, D.C., I grew a sibling of that bush in a pot on my balcony, just for the profusion of blossoms for two or three weeks every spring.

I went out for a run today and was grateful to see forsythia in bloom all around Huntington. But my thoughts today aren’t really about forsythia, or musings on Easters past, but on the color yellow, and all it signifies.

Probably the most common connotation of the color yellow is cowardice. Kenny Rogers, God rest his soul, sang of a young man named Tommy, but “folks just called him yellow,” because they thought that his unwillingness to fight meant he was a coward. Yellow roses are the color of friendship, but usually in a negative way — if you receive a yellow rose, it means that the person you were romantically attracted doesn’t feel the same.

It would be easy to become jaundiced (!) against everything yellow, to interpret its presence as a bad sign.

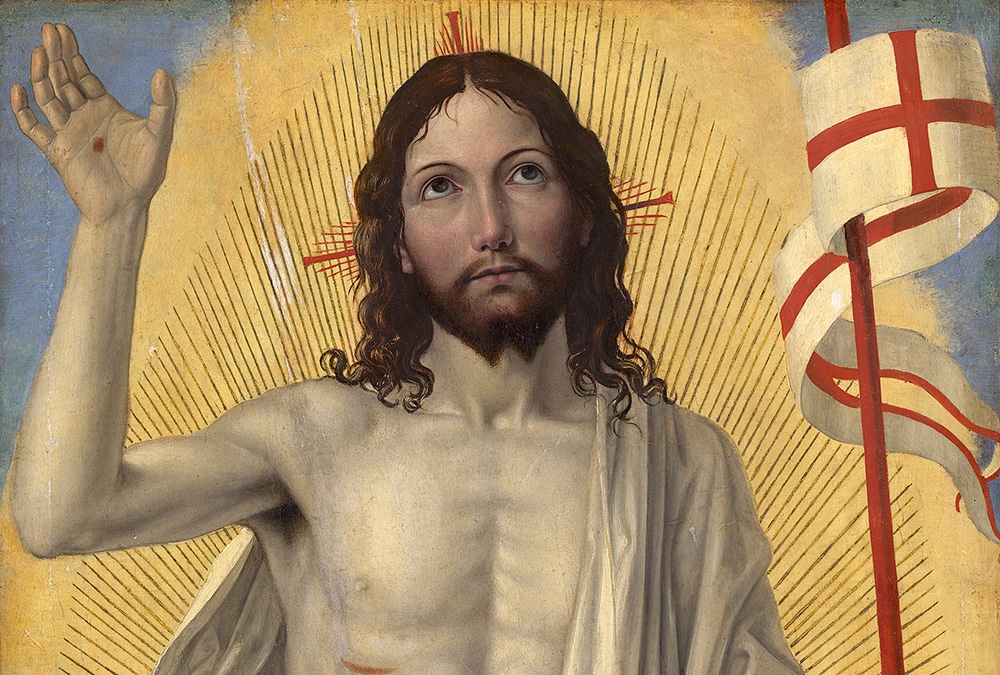

But yellow is also the color of gold, one of the gifts of the wise men to the Baby Jesus, acknowledging his kingship and authority. It’s the color of the flames of the candles that we light on the altar of sacrifice, and the color of the natural beeswax that liturgical candles are made of. It’s the color of the risen sun, a symbol of the Risen Christ who drives out the darkness of sin and death.

And, for people like me, it’s the color that brings joy to us when we see it in our favorite flowers.

But just as my thoughts today aren’t really about forsythia, they aren’t about the color yellow, either. They’re about the way that we approach life in the midst of strife — and especially about how we approach Holy Week knowing that we won’t be celebrating the sacred mysteries at the center of our faith with our fellow Catholics in our parishes this year.

We can view these days through jaundiced eyes, seeing only that which we’re being deprived of. We can blame government officials who have “overreacted” to this crisis; we can even blame bishops who have taken what they regarded as sound advice from the CDC and state health authorities. We can grow angry over the loss of our “rights” as Catholics to receive the sacraments, especially during this week.

And, in the process, we can let the devil distract us from where our true focus should be.

Or we can look at this as an opportunity to strengthen our faith. To unite ourselves with Christians around the world and across the last two millennia who did not have access to the sacraments for very long periods of time. We can increase our fasting and prayer over the next few days, as Christians did in the first centuries, when the Lenten fast was only 40 hours (without any food or water!) rather than 40 days. We can read about St. Mary of Egypt, who repented of her life of prostitution and went to live in the desert, voluntarily depriving herself of the sacraments for the rest of her life, until she received Christ in the Eucharist at Easter, and gave up her spirit.

Just as the color yellow can mean different things to different people depending on how they look at it, we can look at our circumstances and see either spiritual oppression or an opportunity for spiritual growth.

If we truly are an Easter people, we will see the latter.

Scott P. Richert is publisher for OSV.