WASHINGTON (CNS) — When health care chaplains talk about the need for self-care, they really mean it, especially after this past year.

That’s because they have been on call to provide emotional and spiritual support to patients, families and medical staffs in ways beyond what they had ever prepared for when the coronavirus hit the United States last February and since it just surpassed the death toll of 500,000 this Feb. 22.

“This suffering on a daily basis takes an emotional toll, ” said Sandra Michocki, a chaplain at Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore. “In order for it not to swallow us,” she said, chaplains have to remember that God is always with them and “when we’re weary or we’re tired, we show up anyway; that’s all we can do.”

But she also knows they can’t just show up, because they have to be ready to listen, to empathize and help people find strength from their faith or deep within themselves. To do that well, hospital chaplains have had to take care of themselves.

“You’re no good to anyone unless you’re good to yourself,” an expression Michocki’s mom uses, aptly fits the chaplains’ experience this year when they faced not just the onslaught of the coronavirus but also the challenge of doing their ministry differently: by phone or while wearing layers of personal protective equipment.

In interviews with Catholic News Service in late February, these ministers stressed they have kept going this year with everything from prayer, music, exercising, talking with one another, equine therapy, taking care of plants and even stepping aside from work sometimes, just briefly.

And while they recognized that self-care had to be a priority, some of the things they normally did also shifted in the pandemic.

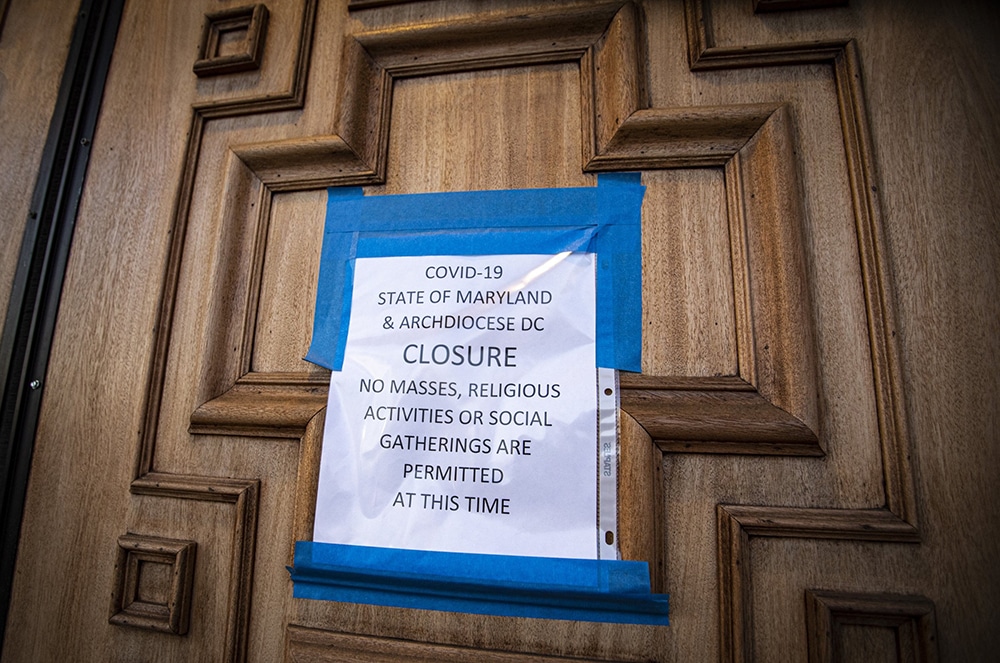

Gavan Meehan, a chaplain at the Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Brunswick, New Jersey, used to swim to decompress from work, but his gym closed in the pandemic. “My self-care as far as exercise went out the window,” he said, although he hiked in the summer when he could.

A parishioner at St. Peter’s Parish in New Brunswick, Meehan said he also felt the importance of Sunday Mass for his work because he would “lift up the faces” of those he cared for during the week at Mass. He can still do this while watching the livestreamed Mass, but he said he misses receiving Communion.

Verna Simpkins, a chaplain at Mercy Hospital in Rockville Centre, New York, who changed from her work clothes in the garage when she got home so as not to bring COVID-19 germs in the house, said listening to gospel music helped her relax.

Simpkins, who is Baptist, said she felt supported by her congregation but only seeing them at Zoom services during the pandemic wasn’t the same as being with them.

“I learned in this season to spend more time with God,” she said.

Vicki Lucas, a hospice chaplain with Holy Cross Home Care and Hospice, part of Holy Cross Hospital in Silver Spring, Maryland, had primarily been visiting patients at their homes before the pandemic and the car rides in between visits were a time to reset.

Now, with her work primarily done by phone, she makes it a point to stand in her yard for a few minutes each hour just to catch her breath a little. The parishioner at St. Camillus Parish in Silver Spring, describes chaplaincy as an encore career after 30 years of doing development work.

She is convinced she found her calling, but she also felt sideswiped by having to change the way she was used to doing things in person to primarily talking to family members and patients on the phone.

For advice on telechaplaincy and just overall support, she often taps into weekly Zoom calls with other members of the National Association of Catholic Chaplains, based in Milwaukee.

Sister Amy Golm, chaplain at Agnesian HealthCare in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, also said Zoom calls get her through, but her calls are with members of her congregation, the Sister of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The sister, who lives alone, said at the start of the pandemic that she needed people and hoped to meet with fellow sisters at least once on the video conference platform.

“Once turned into every Sunday night,” she said, where the sisters have a “standing commitment by Zoom to just check in with each other” and have been doing this since last March.

The 55-year-old said she is the second youngest in the congregation and in the course of the nearly one year of calls, two sisters moved into assisted living and one had open heart surgery. Through the year, she said, the sisters have “managed to keep these connections that are absolutely critical.”

With the unpredictable nature of each day and the overwhelming challenges that might come up, Michocki said she has learned to do what it takes to equip herself before her shift even starts.

Before the pandemic, she might have left the house without praying or eating breakfast and would just take “the day by storm” as she said. But this year, she realized she needed to have her own built-in practices in place.

“I needed to be prayed up; I needed to eat,” she said.

She also said listening to other hospital staff members share what they were going through confirmed she needed to be grounded to be an effective support. “I found that I was carrying a load that didn’t belong to me,” she said, stressing that she needed to deepen her own prayer, quiet times and support system.

She makes sure she gets to Mass each day, and she also says the rosary on the phone with her mom while on the COVID-19 floor praying for those who are sick and those caring for them. She also does equine therapy and said working with horses helps her think about how she communicates with others, which has completely shifted with masks and often by phone.

Michocki admits that one aspect of self-care, to pull back at times from work, is tricky because she is a fixer and a hard worker. But she also knows that being physically and mentally drained takes its toll, so sometimes she simply acknowledges that she needs to take a break and will either get a drink of water, go for a walk, talk to a colleague or cry.

The Rev. Chance Beeler, a minister with the United Church of Christ who is the manager of pastoral and spiritual care for SSM Health St. Joseph Hospital in St. Charles, Missouri, said fellow chaplains frequently check in with one another to make sure they are doing all right, and many of them go to the hospital chapel to pray or meditate, or go outside for a walk, although not as much lately with the recent St Louis cold snap.

He makes it a point to exercise, eat right and do some spiritual reading or mediation. When volunteers were told to stop coming to the hospital, he also took on their job of taking care of the chapel plants, which he described as almost a spiritual practice.

“Lots of those plants had new growth, even in the midst of this time,” he said, surprised by this small but measurable success in a year full of challenges.

Even little signs of hope keep these chaplains going.

Michocki said so much has changed this year on a day-to-day basis; keeping up has required careful navigating.

“It’s all about a balance, ” she added. “You can’t get stuck in sadness, grief or joy.”

– – –

Contributing to this story was Chaz Muth.