“Catholic art provided a means to re-evangelize Reformation-torn Europe with beauty and provided clarity to Church teaching amid chaos.”

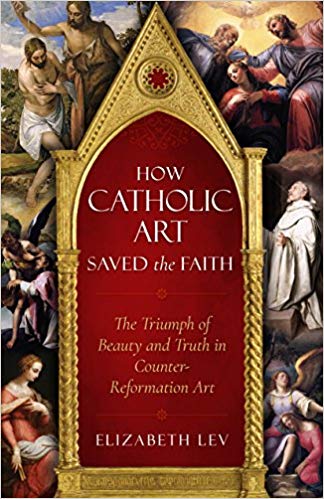

This is the assertion made by Elizabeth Lev, an American-born, well-known art historian, expert, international public speaker, and tour guide, living and working in Rome, who after much research arrived at this conclusion. In fact, it is the title of her most recent work, “How Catholic Art Saved the Faith: The Triumph of Beauty and Truth in Counter-Reformation Art” (Sophia Institute Press, $18.95), which she discussed during an interview with Our Sunday Visitor:

Our Sunday Visitor: You just authored “How Catholic Art Saved the Faith.” How can you make such an assertion?

Elizabeth Lev: If Dostoevsky claimed, “Beauty will save the world,” I propose that beauty, harnessed by the Catholic Church along with truth and goodness, can rescue a faith mired in doubt, confusion and polemics, as indeed it was during the Protestant Reformation. This book wants to remind readers that the Church has sponsored some of the greatest art and artists in history, not merely to give the modern-day tourist something to do between eating gelato in Italy, but to teach, inspire and persuade people of the truth of the Catholic faith.

OSV: What inspired you to write it?

Lev: Teaching Baroque art at Duquesne University for 16 years, I tried to help my young American students decipher the crazy number of names, subjects and dates, by categorizing the works of art according to the contemporary issues they confronted — for example, paintings regarding sacraments or saints. We look at how the subject was previously treated, then how the late 16th and early 17th centuries changed the iconography. My students invariably understood the art better once they knew what it was for. They saw why artistic media and placement matter and why artists would develop certain stylistic techniques, such as making figures protrude toward the viewer, or rapid execution in oil, or a vertical perspective that made the heavens look like they were opening.

As the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation loomed, I recognized many similarities between that society and ours — differing views regarding the sacraments, the magisterium, etc., and especially the harsh, polemical tone taken among people all claiming to be followers of Christ. Aleteia magazine published my series of articles on how the Church used beautiful art to respond to crises, and then Sophia Institute Press asked me to write “How Catholic Art Saved the Faith.” It felt like I have been writing this book for most of my adult life.

OSV: What Catholic art exactly are you referring to?

Lev: [Michelangelo Merisi da] Caravaggio is the most famous painter of this era. Despite the efforts of secular art historians to claim Caravaggio as indifferent to religion, “How Catholic Art Saved the Faith” demonstrates that despite his serious personal failings, Caravaggio was a champion of Catholic art. His “Crucifixion of St. Peter” in Santa Maria del Popolo was the first work to greet most pilgrims coming to Rome, with a vivid, almost photographic rendering of the last moments of Peter’s life. Guido Reni, in character and style the opposite of Caravaggio, painted “The Michael the Archangel defeating Satan,” which was admired even by early American tourists like Nathaniel Hawthorne.

I was thrilled, however, to also feature great women painters in the book, such as Artemisia Gentileschi and Lavinia Fontana. Artemisia is renowned for her “Judith Slaying Holofernes,” but, in this book, I examine this work from the point of view of the heroic battle against sin. Lavinia was the first professional female painter in western art. Discovered and promoted by male prelates, she painted two altarpieces in the male-dominated Roman art scene. Why does art history ignore her? Probably because she was happily married with lots of kids and loved her Church and her faith.

OSV: When you say Catholic art saved the Faith, the Faith was saved from what?

Lev: The wake of the Reformation was devastating for the faithful. Poor catechesis had left people confused about the meaning of sacraments, and the reformers pressed this advantage to deny the real presence of Jesus in the Eucharist and to abolish the Sacrament of Penance. Believers were told that only superstitious fools appealed to saints, and others were taught that nothing we did in this life affected our eternal salvation. Separated from the community of saints, assailed by doubt and left without holy purpose, many of the faithful faltered. Furthermore, the strident tone of sermons and pamphlets broke down communication and dialogue. Catholic art provided a means to re-evangelize Reformation-torn Europe with beauty and provided clarity to Church teaching amid chaos. Clear teaching, inspirational examples and persuasive images played a significant role in helping the faithful recover their Catholic footing in that difficult age.

OSV: Your book discusses the saints and their relationships with Jesus, Mary as teacher and our advocate, and so on. What message about them in particular do you wish your readers will take with them?

Lev: Writing on the saints was very enriching for me because they come in all shapes and sizes, … but also because I realized how art … has helped saints to adapt through the ages. Mary Magdalene, once depicted as a wealthy noble, became the paradigm of penitence during the Catholic Restoration. The mystical saints got pride of place in this era because they see things others can’t. Paintings of St. Francis change from his talking to animals to his rapturous experience of the stigmata. And Teresa of Ávila, well, she is the crown jewel of hagiographic imagery. … Bernini’s Teresa convinces people to be Catholic because it feels beautiful!

Deborah Castellano Lubov writes from Rome.