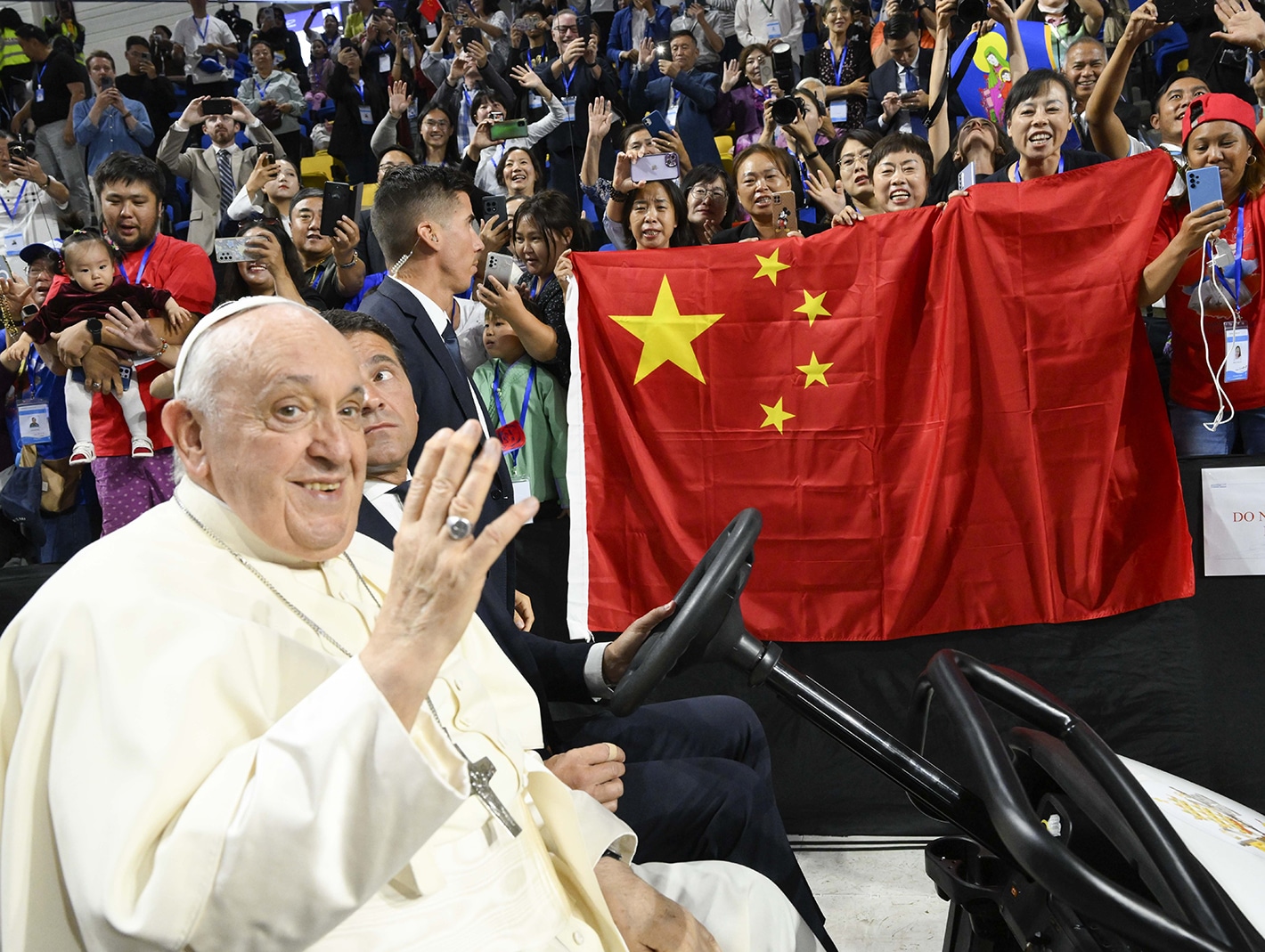

After saying Mass at the end of his recent four-day trip to Mongolia, Pope Francis encouraged Chinese Catholics “to be good Christians and good citizens.” He said this while holding the hands of the bishop of Hong Kong, Stephen Chow, and Chow’s predecessor, Cardinal John Tong, calling them his “brother Bishops.” Francis noted Chow’s and Tong’s presence in sending “a warm greeting to the noble Chinese people.”

The symbolism of the pope’s greeting and admonition is an important and encouraging sign of the pope’s concern for the Catholic Church in China. It is an echo, in fact, of the Apostle St. Paul’s instructions about Christian citizenship in his letter to the Romans.

Of course, China’s human-rights record is abysmal. This includes its suppression and persecution of various religions and religious practices, including the Catholic Church. And Pope Francis has been criticized for not doing enough to condemn China’s atrocities. At times, it even appears as though he has been complicit, at least by omission, in the Chinese government’s interference with internal Church matters. This includes China’s insistence on approving (and at times presuming to appoint) Catholic bishops.

The Vatican and China

Nothing that Pope Francis said in Mongolia (or in this column) should be interpreted as minimizing China’s egregious behavior toward the Church and Chinese Christians. But in the delicate context of the relationship of the Church to the Chinese government, Pope Francis’ strategic vision may be more farsighted and acute than we think.

On the flight back to Rome, the pope expanded on his gestures in Mongolia. “The relations with China are very respectful,” he said. “They are very open, let’s put it that way.” This may indicate that Pope Francis’ work on behalf of the liberty of Chinese Christians is probably more involved than most of us realize.

Given both the precarious position of the Church and China’s authoritarian government, the pope recognizes that cautious, careful steps will do more to advance religious liberty for Catholics than grand denunciations of China’s persecution or interference. It is one thing for disinterested critics to chastise China; quite another for the shepherd of Chinese Christians to do so.

In chapter 13 of his Epistle to the Romans, St. Paul instructed Christians in Rome to “be subordinate to the higher authorities” because governmental authority is a participation in the authority of God. “There is no authority except from God,” he explained, and governments “have been established by God.” This instruction is especially relevant to the situation in China, as the persecution of Christians in Rome was, if anything, more severe than China’s persecution of Catholics. Roman authorities, St. Paul continued, “are ministers of God.” Thus, even in the face of persecution, St. Paul instructed the Romans “to be subject not only because of the wrath but also because of conscience.” Thus, he concludes, “pay to all their dues … respect to whom respect is due, honor to whom honor is due.”

Lessons from St. Paul

At least two lessons about China can be drawn from St. Paul’s admonitions. The first is that Christians are obligated (with a caveat noted below) to obey the laws even of bad governments. The fact that a government is oppressive does not give Christians license to disregard all the laws or regulations of that government. With regard to the aspects of government in which “respect” and “honor” are due, they should be paid. This is the case even when a government is not due to either of those things in some (or even many) of its actions. Where honor is due, it ought to be paid.

But, second, this principle is not unlimited. When the laws of governments require Catholics to disobey the laws of God, those laws are not “due” honor or respect. St. Paul, himself, demonstrated this exception by his refusal to stop preaching the Gospel, which resulted in his arrest and execution during the Neronian persecution. When a government institutes a law that forbids an action that Christian faith compels, the government is not due obedience to that law.

With this background, Pope Francis’ admonition to Chinese Catholics to be “good Christians and good citizens” makes perfect sense. On one level, to be a good citizen is a practice of Christian virtue. We can be good citizens in any number of kinds of government. And to the extent we can, we must. On the other hand, however, being a good Christian is not simply the same as being a good citizen. While our Christian faith teaches us to be good citizens, that faith is not defined by citizenship. Faith transcends citizenship.

I have to believe that Pope Francis has something like this in mind. And at least one person who made the difficult journey from China to attend the Mass in Mongolia seems to have understood. “Let me tell you,” she said, “I feel ashamed to hold the [Chinese] flag.” But, she added, “I need to hold it and let the pope know how difficult it is for us.” In a subtle yet encouraging way, I believe that Pope Francis gave encouragement to this woman and her fellow Chinese Catholics. We should not gainsay Francis’ understated symbolic public gestures while he works on substantive changes out of the public view. Hold fast, he seems to be saying; I am working on your behalf.