Here is today’s quiz: What 19th-century novel points the way to a lasting solution to the racial tensions afflicting America today?

If you said “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” you’re wrong. As President Abraham Lincoln remarked, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s picture of slavery helped bring on the Civil War, but that’s about all. The correct answer is Mark Twain’s classic “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.”

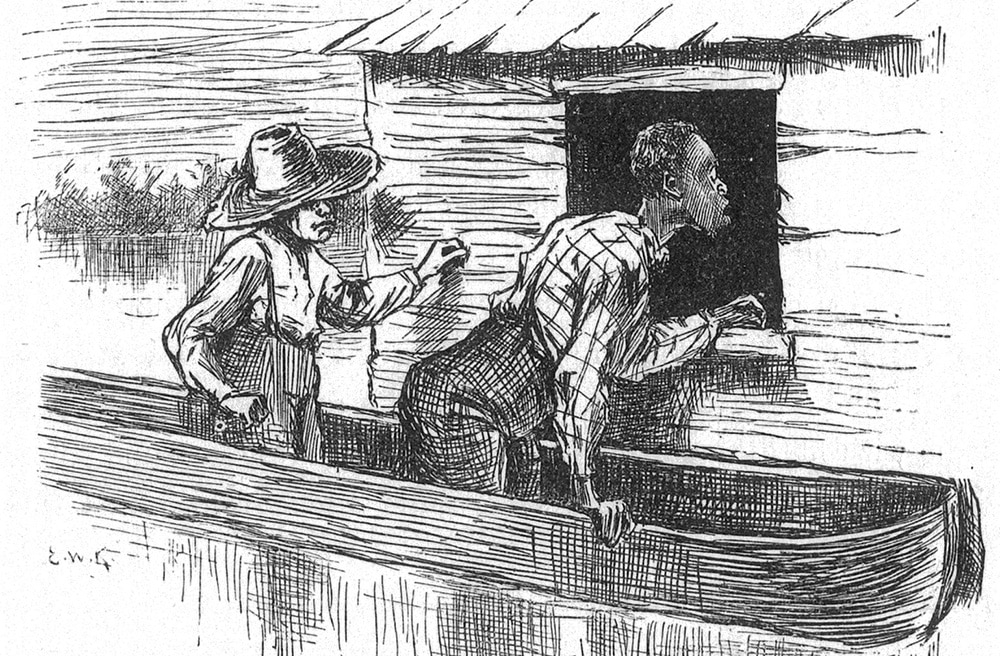

Sometimes called the first Great American Novel, “Huckleberry Finn” is cast as a dialect narrative by a free-spirited boy escaping a vicious father and a repressive society in company with an escaped Black slave named Jim. The book recounts their picturesque and sometimes frightening adventures as they raft down the Mississippi in pursuit of what each hopes will be freedom.

More than just a colorful tale, the book paints a picture of slavery before the Civil War as filtered through the troubled conscience of an unlettered but perceptive youth who finds himself obliged to weigh lived experience against the self-righteous code of a society that approves ownership of some human beings by others.

Rather than preaching, Twain takes us inside Huck’s mind as he wrestles with his ethical dilemma. In the book’s central passage, Jim has been apprehended and is being held in custody pending location of his owner. Huck knows who that is — an elderly woman back home who has been kind to him. Taught to consider assisting a runaway slave gravely sinful, he composes a letter telling the old lady where she can claim her property.

“I felt good and all washed clean of sin for the first time in my life,” Huck recalls, “and I knowed I could pray now.” But then he starts to think. He remembers the jolly times he and Jim have had laughing and singing together on the river, and the times Jim has stood watch for him so he could sleep longer. He recalls other instances of Jim’s goodness and kindness, as well as the time the Black man told him “I was the best friend old Jim ever had in the world.”

Then his eye strays to his letter betraying Jim.

“I took it up, and held it in my hand. I was a-trembling, because I’d got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself: ‘All right, then, I’ll go to hell’ — and tore it up.”

Twain wrote most of “Huckleberry Finn” soon after its predecessor, “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” appeared in 1876. Unsure how to end the story, however, he waited several more years before finishing the book in 1884. At a loss for a conclusion, Twain finally turned to Tom Sawyer (imported from the earlier novel) who concocts a harebrained scheme for freeing Jim that nearly costs Jim, Huck and Tom their lives. After that comes a rushed and unpersuasive happy ending that sends the reader away feeling somehow cheated.

But to his everlasting credit, Twain got the solution to the race problem exactly right. In the end, he makes clear, the only lasting answer lies in recognizing and celebrating our common humanity.

And now? Now some activists indulge in symbolic gestures like toppling the statues of dead generals that provoke without persuading while others busy themselves promoting white guilt and reparations. If there is a moral here, it’s that Mark Twain’s fiction, in contrast to the contemporary churning of ceaseless societal unrest, marks out the authentic pathway to social equity and peace.

Russell Shaw is a contributing editor for Our Sunday Visitor.