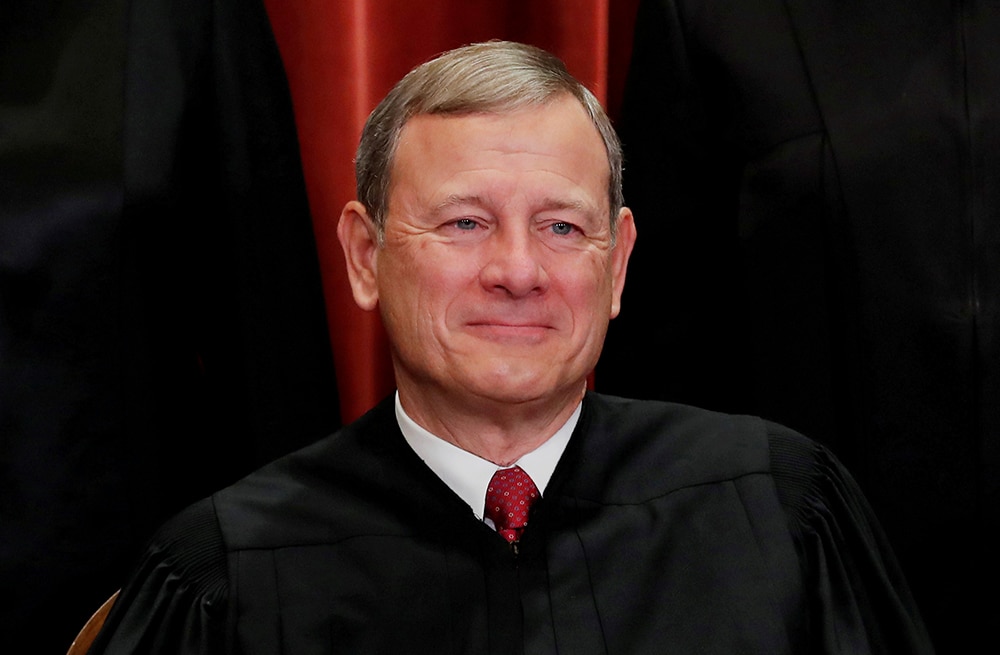

Disappointed prolifers were predictably angry at Chief Justice John Roberts for providing the fifth vote in the five-member Supreme Court majority that last month struck down a Louisiana law requiring doctors who do abortions to meet one mildly restrictive prescription. It was no surprise that the court’s four liberals — Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer (who wrote the opinion), Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan — voted as they did, but Roberts, a conservative, came as a shock.

Disappointed prolifers were predictably angry at Chief Justice John Roberts for providing the fifth vote in the five-member Supreme Court majority that last month struck down a Louisiana law requiring doctors who do abortions to meet one mildly restrictive prescription. It was no surprise that the court’s four liberals — Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer (who wrote the opinion), Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan — voted as they did, but Roberts, a conservative, came as a shock.

Hold on though. Granted, it would have been gratifying if the chief justice had supported the Louisiana law instead of citing stare decisis as grounds for voting against. But a sober reading of his opinion as a whole suggests that prolife critics may have reasons for thanking him in the not-too-distant future.

With hindsight, it’s unfortunate that the Louisiana case ever reached the Supreme Court. Just four years ago it overturned a virtually identical Texas law prescribing that doctors who perform abortions have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. But note that the chief justice specifically refrained from endorsing the substance of the opinion by Breyer, who also authored the majority opinion in the Texas case. Instead, Roberts took a different line that points to the possibility of a different outcome in future cases involving different state laws.

Two such cases from Indiana (both of them presently go by the name Box v. Planned Parenthood) are now in the 7th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, which the Supreme Court, two days after its Louisiana decision, told to take a fresh look at the laws involved. One requires that women be offered ultrasounds before abortion, the other that parental consent precede abortions performed on minors.

What Roberts said now becomes important. He argued for a formula that, subtly but truly, tips the balance more in favor of restrictive state laws than it’s been tipped for years.

Its basic idea is that in considering a statute adopted by a state with the aim of restricting abortion, the court should begin by considering whether a particular law serves a rational state interest — such as protecting unborn human life. If so, the court then should examine whether the law places a “substantial obstacle” in the way of a woman seeking an abortion. If it does, the law would be unconstitutional. But if it doesn’t, the law would stand.

This formula is favored by the four justices — Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh — who wrote dissents in support of Louisiana’s admitting privileges statute. Now add Roberts to that list and you have five — a majority of the Supreme Court as presently constituted. While some prolifers deplored what Roberts did in the Louisiana case, abortion supporters understood very well what had happened and were quick to voice concern.

Looking to the future, the possibilities for new state laws are numerous and well worth exploring. Besides the ultrasound and parental consent requirements in the Indiana cases mentioned above, other options include such things as banning sex selection abortions and setting a time in pregnancy beyond which abortions could not be performed except for compelling medical reasons.

It hardly needs saying that measures like these fall far short of unconditional recognition of the unborn child’s right to life. But the happy day when that particular bit of sanity has been restored will require genuine conversion — not just in the Supreme Court but in American society as a whole. Pending that, prolifers would be well advised to take advantage of the limited but real opening offered them by John Roberts and his four colleagues.

Russell Shaw is a contributing editor for Our Sunday Visitor.