Parents’ vocation is to help your children become capable of their vocations. Each vocation is the specific shape of one’s own discipleship, and discipleship itself is a matter of love. Discerning a vocation means learning how to perceive and respond to the Lord’s will within and through the concrete circumstances of your own life, for the good of others and thus for your own ultimate good.

In the Gospels, disciples are presented as “those who hear the word of God and act on it” (Lk 8:21). The deeply personal aspect of this hearing and acting is founded in the Word of God spoken to you directly so that you are charged with the mission of acting. That’s vocation.

The Benedict Option?

When St. Benedict of Nursia wrote his Rule for monastic life, he captured the challenge and privilege of the call to discipleship in two lines. His Rule opens with a direct address to each of the monks under his care: “Listen carefully, my son, to the master’s instructions, and attend to them with the ear of your heart.” Benedict is taking on the role of father (or abbot), while “the master” is the Lord alone. It is the Lord’s instructions that matter most of all. The whole basis of this intentional life lived together in the monastery is in striving to give the whole of your attention to the Lord’s voice. The conditions of the monastery are designed to make this deep listening more likely. Everything begins with “hearing the Word of God,” indeed of becoming ever more capable of hearing that Word well, with generosity and devotion.

A second line from later in the Prologue of Benedict’s Rule speaks to what all this concentrated listening is for, in the end. As Benedict puts it, “The Lord waits for us daily to translate into action, as we should, his holy teaching.” The point of listening for the Lord is, ultimately, to translate the Word of God into your actions. Put another way, the Word is to take flesh in you. This isn’t to say that Benedict is imagining new incarnations over and over again, as if what happened with the Virgin Mary happens in the same way with every disciple. Rather, Benedict is forming the monks in his care to receive the Son of Mary with generosity and devotion so that they may, in the end, give their own lives to the service of loving of him and, therefore, loving those whom the Lord himself loves. Benedict and every abbot after him is a father, whose own vocation is to help those entrusted to his care become capable of their vocations.

We might call this the “Benedict Option” for parenting. This does not mean a denial of society or a final removal from the happenings of the world. What it means is intentionally, skillfully and even artfully creating the conditions and cultivating the habits that make hearing the Word of God more likely and more robust, while also guiding those entrusted to your care toward translating God’s Word into their own actions, commitments and sacrifices. No one can answer another person’s call to discipleship for them or discern another person’s vocation on their behalf. In other words, parents cannot do vocational discernment for their children. What parents can and are in fact called to do is equip and empower children for the challenge and privilege of discerning the Lord’s call in their lives.

Responding to the challenges

Prior to founding his monastery, St. Benedict had gone to Rome as a young man to study. He had aspirations of growing in holiness, but he soon found that the culture in Rome was not at all conducive to those desires. The city was drowning in a swirl of passions, it had no space for deep listening, its pervasive influences were generally directed away from charity, and its customs did not lead toward true communion with others.

Benedict left the city and took deliberate steps to establish different conditions from what he just happened to find in the world of his day. He separated from the prevalent culture he encountered in Rome to be formed and to form others in a more intentional culture. The point was to create the conditions and establish the customs aimed at loving the Lord well and, ultimately, loving this world well in obedience to the Lord.

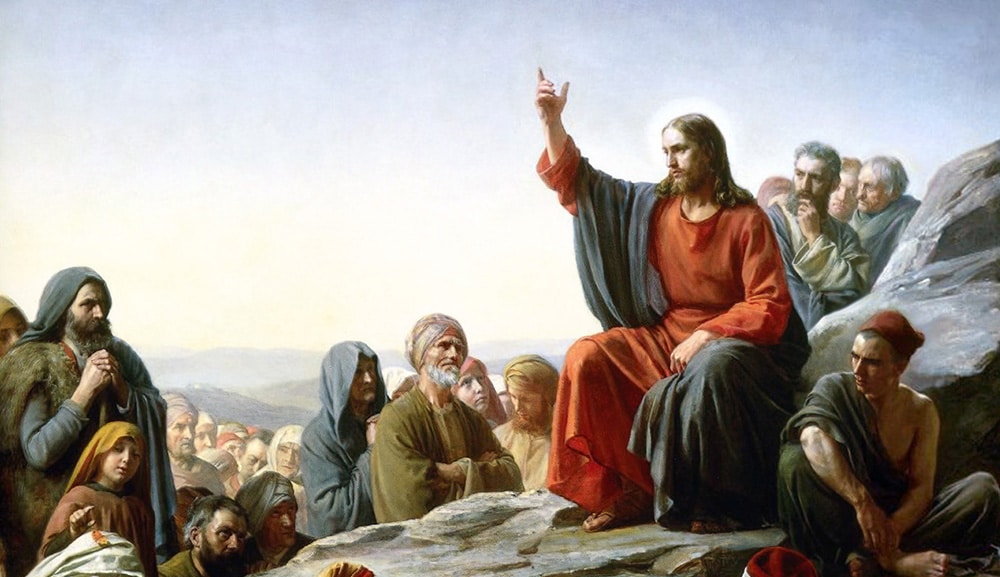

Benedict’s actions followed Christ’s own example. When Christ took his disciples up the mount and away from the crowd in Matthew 5, he did so to initiate them into a new culture so that they could return to the crowds with him, to share in his mission. Likewise, when Christ took his disciples away to a lonely place (cf. Mk 6:31; Mt 14:13; Lk 9:10; Jn 6:3; etc.), he removed them from what had become the typical way of things so as to form them in his ways and customs directly.

The point of these episodes of formation is always to make the disciples into the kind of people capable of receiving God’s will and acting on it. The same thing happens in that unforgettable encounter on the first day of the Resurrection, when Jesus finds two of his would-be disciples on the road to Emmaus (cf. Lk 24:13-35).

One way of reading the Emmaus episode is to see it in three parts: the first focuses on the condition the wanderers were in when Jesus found them (vss. 13-24), the second focuses on what Jesus does for them (vss. 25-30), and the third focuses on how the wanderers changed and thus responded (vss. 31-35).

Following Christ

We might describe the condition of the wanderers as Jesus found them according to four marks. First, they are disoriented and heading in the wrong direction, away from Jerusalem, where the mystery of God’s love has broken open in the Resurrection. They are moving back toward their lives without Jesus. Second, they seem to know a lot about what has taken place over these three mysterious days, but they are confused and don’t know how to make sense of things. Third, they are chatty and don’t spend a lot of time listening; they just talk and talk and talk. And fourth, they are not just sad, but indeed hopeless, even speaking of their hope in the past tense: “But we were hoping that he would be the one to redeem Israel” (vs. 21). These wanderers are disoriented, confused, chatty and sad.

What does Jesus do for them? First, for these wanderers who were oh-so-chatty and did not listen, he silences them: “Oh, how foolish you are!” (vs. 25). Second, for these wanderers who had no clue how to make sense of things, he reconfigures their memories by teaching them the Scriptures aright: “beginning with Moses and all the prophets …” (vs. 27). Third, for these wanderers who expected a Messiah that exercised more power in just the same way that all the others powerbrokers of the world wielded power, he teaches them how true power — divine power — comes as mercy, as the willingness to suffer for and with the downtrodden: “Was it not necessary that the Messiah should suffer these things …” (vs. 26). And finally, for these wanderers who are empty and hollow, he feeds them with himself — the Word made flesh: “He took bread, said the blessing, broke it, and gave it to them” (vs. 30). Jesus creates the conditions of silence for them to hear the Scriptures, then he schools them in the ways of mercy and gives himself to them in the breaking of the bread.

What becomes of these two wanderers? They answer the call to discipleship. Having received the Word of God, they now take a new mission with great joy, going in haste back to Jerusalem to proclaim the good news: “So they set out at once … then the two recounted what had taken place … and how he was made known to them in the breaking of the bread” (vss. 33, 35).

Seen as a whole, Jesus diagnoses their condition, then acts upon them and for them in a deliberate and skillful manner, so that they might receive him well and respond with their own passion and sacrifice to bring forth good news. Jesus did not force them to do his will; rather, he made it possible for them to receive and respond to him freely, out of love. Crucially, they are the ones who had to actually do it.

Those four actions of Jesus at the end of Luke’s Gospel are anticipated in the same Gospel’s beginning. That anticipation comes in the person of the first and perfect disciple: Mary, Mother of God. She is the one who never fails to hear the Word of God and act on it. She is from the beginning what the two travelers to Emmaus become in the end. As such, the pattern for laying the foundation for vocational discernment is found in her.

In the next two letters, contemplating Mary will help us, as parents, recognize how we are called to help form our children for vocational discernment. Jesus forms would-be disciples to become what his Mother always is: the one who hears the Word of God and acts on it. Parents have the privilege and responsibility of sharing in Jesus’ work, just as saints like Benedict did in their own time and place.

Sincerely,