Speaking to a crowd of 43,000 in a Cleveland stadium in 1935, Father — later Archbishop — Fulton Sheen, already on his way to becoming one of the best known religious figures in the country, said this: “In the future there will be only two great capitals in the world, Rome and Moscow; only two temples, the Kremlin and St. Peter’s … but there will be only one victory — if Christ wins, we win, and Christ cannot lose.”

And at a date unknown, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, reminded of the need to take the pope’s views into consideration, is said to have sneered: “How many divisions has the pope got?”

Taken together, the two quotations reflect the seething gulf of hostility and suspicion between Catholicism and communism before, during and after World War II. Especially after. Especially concerning the Church of Silence.

The birth of the Church of Silence

To a great extent, the Church of Silence — a name often applied to the Catholic Church in communist-ruled postwar Eastern Europe — had its birth just over 75 years ago. The reality it signified had its origins at a top-level conference in early 1945 at the Crimean city of Yalta.

Taking place while the war still raged but victory by the Allies had become certain, the Yalta conference brought together President Franklin Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Stalin to discuss, among other things, the postwar configuration of Europe.

At that time, the Red Army was ploughing into Germany from the north and south, moving into Hungary and Czechoslovakia, and threatening Vienna. Largely in recognition of the facts on the ground, the negotiators at Yalta agreed that the Soviet Union would enjoy postwar hegemony in eastern and central Europe. Stalin promised free elections in the countries involved — a promise easily given and quickly broken.

A year later, with the war over and the postwar landscape settling into place, the consequences were summed up by Churchill in a memorable phrase that was part of a memorable speech delivered at Westminster College in Missouri.

“From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic,” he declared, “an Iron Curtain has descended across the continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of central and eastern Europe … subject, in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and in many cases increasing measure of control from Moscow.”

And behind that Iron Curtain, the Church of Silence had been born and was now struggling to survive.

Another persecution begins

According to Cambridge University historian John Pollard, Eastern Europe’s new communist masters at first dealt with the Catholic Church with a relatively light hand. But under pressure from Moscow, where stepped-up Stalinist repression of religion had begun, the screws were tightened starting in 1948.

“The Church came under attack in the Baltic States, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania and Yugoslavia,” Pollard writes in his exhaustive study “The Papacy in the Age of Totalitarianism.” “Very similar policies were applied in all these countries, based on the ideology of atheistic materialism and the Soviet experience of three decades of the ‘Godless campaigns.'”

Elements of the new anti-Church program included nationalizing Church schools, ending religious instruction in state schools and sometimes in private ones, creating new, secular youth programs in competition with or in place of those of the Church, confiscating monasteries and convents, forbidding clergy and religious to wear distinctive garb, and cancelling existing concordats between local governments and the Holy See.

In several countries, too, the communists sought — with some success — to divide the Church by setting up organizations of collaborationist clergy and so-called “peace priests,” who received promotions and other favors in exchange for supporting the regime.

Especially notable features of the anti-Church campaign were the show trials of those years in which Church leaders in several countries were tried and convicted for allegedly treasonous acts or collaboration with Nazi or fascist rulers during the war.

Among those so targeted were Archbishop, later Cardinal, Aloysius Stepinac of Zagreb in Yugoslavia, whom Pope John Paul II declared a martyr and beatified, and Cardinal Josef Beran of Prague, Czechoslovakia, who had spent three years in Dachau and other concentration camps for opposing the Nazis, and whom the communists then sentenced to another 16 years in prison. His beatification process began in 1998.

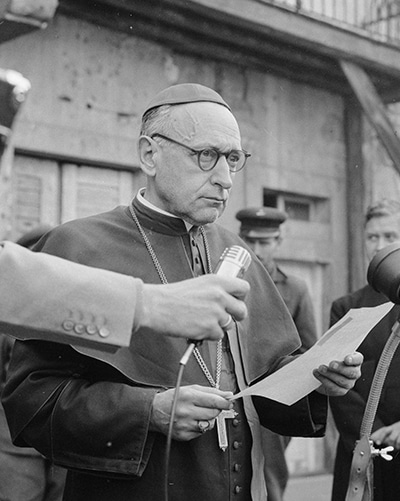

The case of Archbishop, later Cardinal, Jozsef Mindszenty of Esztergom, primate of Hungary, is particularly notable. Although his anti-Fascist record was, in Pollard’s words, “impeccable,” and as bishop of Veszprem during the war he had protested the confinement of Jews in ghettos and their deportation from the country, he nonetheless was imprisoned by the communists and accused of spying, treason and currency manipulation.

Historian Michael Burleigh in his book “Sacred Causes” writes that the attack on the churchman “was not simply designed to destroy the primate or to intimidate the Catholic Church, but to show ordinary Hungarians that if a cardinal was not safe, nor were they.”

“Denied proper sleep for nearly 40 days,” Burleigh writes, “Mindszenty was interrogated through the nights, an experience interspersed with extended torture sessions in which a police major assaulted him with a rubber truncheon. Mysterious doctors were on hand to administer drugs, which Mindszenty was certain were also being mixed with his food. …

“After a month of this mistreatment, Mindszenty was prepared to sign documents, the contents of which he was scarcely cognizant of, and whose dates and facts were altered to suit the case the communists were preparing. He also wrote to the minister of justice, confessing his illicit involvements with the British and Americans in order to bring about a federal monarchy in central Europe under the Habsburgs, and offering to resign to pre-empt the need for a trial.”

Following a three-day trial during which the Cardinal appeared dazed — in his own words, “a man broken in mind and in body” — and his guilt was taken for granted from the start, he was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment.

The Church’s position

In response to the communist onslaught against the Church of Silence, Pope Pius XII (r. 1939-58) and the Vatican fought back as best they could. There was little to be done directly on behalf of persecuted Catholics behind the Iron Curtain, but Rome could — and did — labor mightily to prevent further expansion of communism westward.

This was especially the case in Italy, where Pope Pius’s efforts were credited with contributing significantly to communist defeats in the 1948 and 1950 general elections that they were widely thought to have a good chance of winning. In the face of that threat, which would have been disastrous not only for the Church but for Western democracy, the pope called on Catholics to turn out and vote while threatening those who supported communist candidates with excommunication.

The pope’s tough stance was mirrored in a decree dated June 28, 1949, issued by the Holy Office, predecessor of today’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. To the question of whether it was allowable to join the communist party or support it, the answer was no, with this explanation: “communism, in fact, is materialistic and anti-Christian; the leaders of communism, though they sometimes declare in words that they do not fight against religion, nevertheless, in reality, whether in action or in doctrine, show themselves to be hostile to God, to the true religion, and to the Church of Christ.”

In time, communist repression had its predictable result, though one apparently unforeseen by the communists themselves. People who for years had been intimidated into knuckling under to their oppressors finally rose up, said “Enough!” and rebelled. The first largescale uprising took place in Hungary in 1956.

At first it seemed as if the Hungarian revolution were, marvel of marvels, a great success. But that lasted only until Russian tanks came rumbling through the streets of Budapest, crushing the revolution and the revolutionaries with brutal force.

Cardinal Mindszenty, freed from prison at the start of the revolution, now fled for safety to the American embassy. And there he remained for the next 15 years. In 1971, a deal was negotiated allowing him to leave the embassy and go to Vienna. Although he stepped down as primate of Hungary, the Holy See left the position unfilled until after his death in 1975.

By now, though, times had changed. The Vatican was no longer the Vatican of Pius XII. Pope John XXIII, who succeeded him, had granted an audience to the atheist son-in-law of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and published an encyclical, Pacem in Terris, calling for peace. The Second Vatican Council had met and, to the dismay of some participants, nowhere in its documents so much as mentioned communism, much less condemned it.

And now Pope Paul VI and his secretary of state, Cardinal Agostino Casaroli, were pursuing a policy of Ostpolitik (Eastern policy) that called for coming to terms with the communist regimes of Eastern Europe. Instead of confronting them, it appeared, the Church now asked only that it be allowed to have a reasonably free hand in conducting its internal affairs.

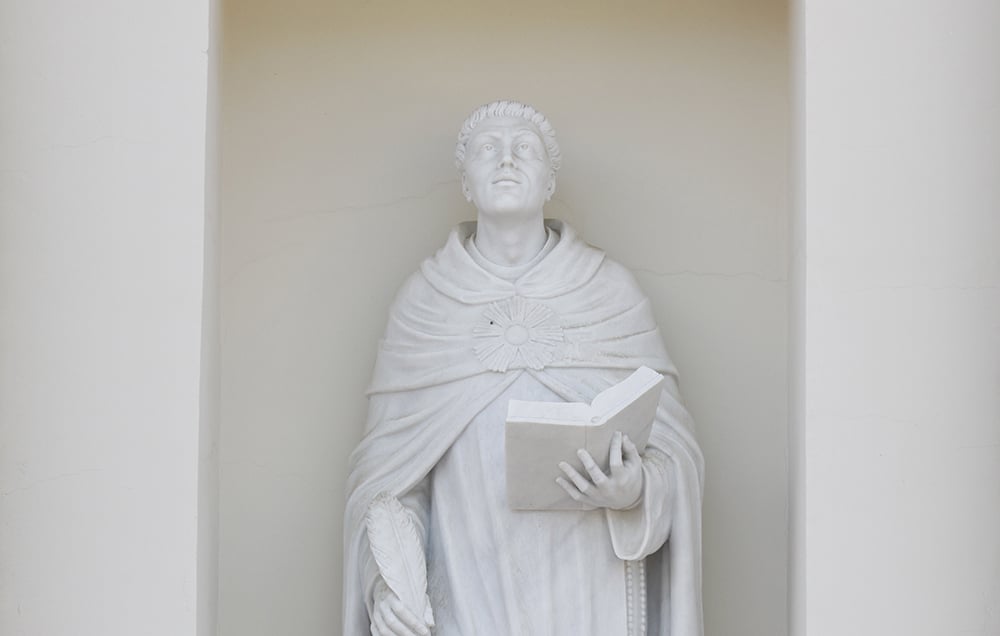

| ‘Divini Redemptoris’ |

|---|

| The Catholic Church grasped the menace of communism and the threat it posed to the Faith well before World War II and the emergence in communist-dominated Eastern Europe of the postwar Church of Silence. The most authoritative prewar statement on this subject in its theological and philosophical roots was Pope Pius XI’s encyclical Divini Redemptoris (“The Divine Redeemer”), dated March 19, 1937 — not coincidentally, the feast of St. Joseph, the patron saint of workers.

Declaring that “society is for man and not vice versa,” the encyclical says communism “impoverishes human personality by inverting the terms of the relation of man to society” (Nos. 29, 30). As for the truth about the human person, Pope Pius sums it up this way:  “[Man] has a spiritual and immortal soul. He is a person, marvelously endowed by his Creator with gifts of body and mind. He is a true ‘microcosm,’ as the ancients said, a world in miniature, with a value far surpassing that of the vast inanimate cosmos. God alone is his last end, in this life and the next. By sanctifying grace he is raised to the dignity of a son of God, and incorporated into the Kingdom of God in the Mystical Body of Christ” (No. 27). Based on this soaring vision of the human person, the pope then sketches the proper relationship between the individual and society — a relationship that he accuses communism of getting disastrously wrong: “Man cannot be exempted from his divinely imposed obligations toward civil society, and the representatives of authority have the right to coerce him when he refuses without reason to do his duty. Society, on the other hand, cannot defraud man of his God-granted rights. … Nor can society systematically void these rights by making their use impossible. It is therefore according to the dictates of reason that ultimately all material things should be ordained to man as a person, that through his mediation they may find their way to the Creator” (No. 30). |

The collapse of communism

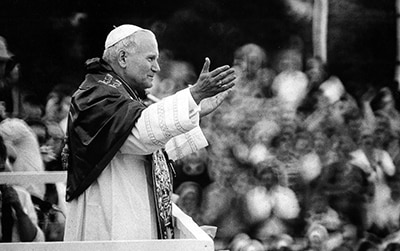

Then, in 1978, the pendulum swung again. Pope Paul died in August and, after the one-month pontificate of Pope John Paul I, who died of a heart attack, the cardinals in conclave surprised the world — and perhaps themselves — by choosing the first non-Italian pope since 1522: Cardinal Karol Wojtyla of Krakow, Poland. He took the name John Paul II, and his first words to the Church and the world, spoken just after his election from the loggia of St. Peter’s Basilica, were “Be not afraid.”

Many people contributed to the collapse of the Soviet empire in Eastern Europe, but the names of three especially stand out: U.S. President Ronald Reagan, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Pope St. John Paul II. The role John Paul was destined to play became obvious during his first trip home to Poland in June of 1979.

The papal visit was greeted by a huge upsurge of Polish nationalist sentiment and religious fervor, with an estimated 13 million people turning out to see John Paul, hear him and pray with him. At the trip’s last public event, when the pope invited the people to bring forward several large crosses for his blessing, people began raising crosses of their own — many thousands of them, and many homemade — to receive his blessing.

“These young people of Poland,” Ronald Reagan remarked soon after, “had spent their entire lives under communist atheism. Try to make a Polish joke out of that.”

The decade that followed saw many other dramatic events in Poland and elsewhere, but what happened during that trip home by the Polish pope furnished a spark that ignited an unquenchable blaze. When the Berlin Wall fell on Nov. 9, 1989, it was only a matter of time before the communist empire would dissolve and disappear — and the Church of Silence would be no more.

In May 1991, in his encyclical Centesimus Annus (“The Hundredth Year” — referring to the time since the publication of Pope Leo XIII’s landmark social encyclical Rerum Novarum), Pope John Paul pointed to three reasons for the fall of communism in Eastern Europe.

The first reason was the violation of workers’ rights: “The fundamental crisis of systems claiming to express the rule and indeed the dictatorship of the working class began with the great upheavals which took place in Poland in the name of solidarity,” he wrote (Centesimus Annus, No. 23).

The second reason was the inefficiency of the economic system in tandem with a view of human life that left God out of the picture. “When this question is eliminated,” John Paul declared, “the culture and moral life of nations are corrupted” (Centesimus Annus, No. 24).

And finally, he said, “the true cause” of what happened: “the spiritual void brought about by atheism. … [The events of 1989] are a warning to those who, in the name of political realism, wish to banish law and morality from the political arena” (Centesimus Annus, No. 24).

The collapse of communism did not solve all the problems of what up to then had been the Church of Silence, and many new problems have arisen since. But what happened then is a lesson the Church of Silence continues to teach today to those with long memories and eyes to see.

Russell Shaw is a contributing editor for Our Sunday Visitor.

| What the Catechism says about communism |

|---|

The Catechism of the Catholic Church does not refer specifically to communism. But it does contain a scathing indictment of totalitarianism that undoubtedly fits communist regimes wherever, historically, they have come to power: “Moral judgment must condemn the plague of totalitarian states which systematically falsify the truth, exercise political control of opinion through the media, manipulate defendants and witnesses at public trials, and imagine that they secure their tyranny by strangling and repressing everything they consider ‘thought crimes'” (No. 2499). The Catechism also contains a passage on authority and the common good by which communism or any other system of political governance can be judged: “The diversity of political regimes is morally acceptable, provided they serve the common good of the communities that adopt them. Regimes whose nature is contrary to the natural law, to the public order, and to the fundamental rights of persons cannot achieve the common good of the nations on which they have been imposed…. “Authority is exercised legitimately only when it seeks the common good of the group concerned and if it employs morally licit means to attain it. If rulers were to enact unjust laws or take measures contrary to the moral order, such arrangements would not be binding in conscience. In such a case, ‘authority breaks down completely and results in shameful abuse'” (No. 1901, 1903 — quotation from Pope St. John XXIII, Pacem in Terris, No. 51). |