Even for Catholics who know the Faith well, there is much mystery surrounding 2,000 years of Church history — even events that some might call “skeletons in the closet.” Many of these controversial moments have been explained and debunked, but they still elicit snide comments and even heated discussions from those inside and outside of the Church.

“Church history is alive, still evoking emotions, generating discussions, and arousing controversies,” writes Polish journalist and filmmaker Grzegorz Gorny in his new book “Vatican Secret Archives: Unknown Pages of Church History” (Ignatius Press, $34.95), co-authored by Janusz Rosikon. Gorny notes that certain events and people — the Crusades, the Templars, the Inquisition, the conquistadors, the trial of Galileo Galilei, the French Revolution, the Spanish Civil War, Pius XII and the Holocaust — “belong not only to the past, but also to the present, due to their ceaseless presence in public debates.”

“Church history is alive, still evoking emotions, generating discussions, and arousing controversies,” writes Polish journalist and filmmaker Grzegorz Gorny in his new book “Vatican Secret Archives: Unknown Pages of Church History” (Ignatius Press, $34.95), co-authored by Janusz Rosikon. Gorny notes that certain events and people — the Crusades, the Templars, the Inquisition, the conquistadors, the trial of Galileo Galilei, the French Revolution, the Spanish Civil War, Pius XII and the Holocaust — “belong not only to the past, but also to the present, due to their ceaseless presence in public debates.”

‘The Church needs the truth’

The authors begin with the origins of the pope’s archives, which, their research shows, is uncertain. Gorny and Rosikon write that St. Peter himself had his own small archive. Unfortunately because of three centuries of persecutions and devastating waves of barbaric invasions, we do not know what exactly the ancient archives contained. Reportedly, they kept administrative and financial documents, acts of the martyrs, biblical manuscripts, theological texts, testaments and legacies.

Undoubtedly, however, the most surprising revelation is that, because of the frequent struggles between powerful Roman families, what did manage to survive the attacks on Rome was destroyed by the Romans themselves.

Therefore, the authors write, the oldest surviving files of papal documents do not date back any earlier than the pontificate of Pope Innocent III (1198-1216).

Many documents, Gorny and Rosikon explain, later followed the popes to France during the Avignon papacy (1309-77). Other documents during the Sack of Rome in 1527 — several days of murder, rape and plunder of the city by the troops of the Emperor Charles V — were used as tinder for fires, bedding for stables and insoles for shoes.

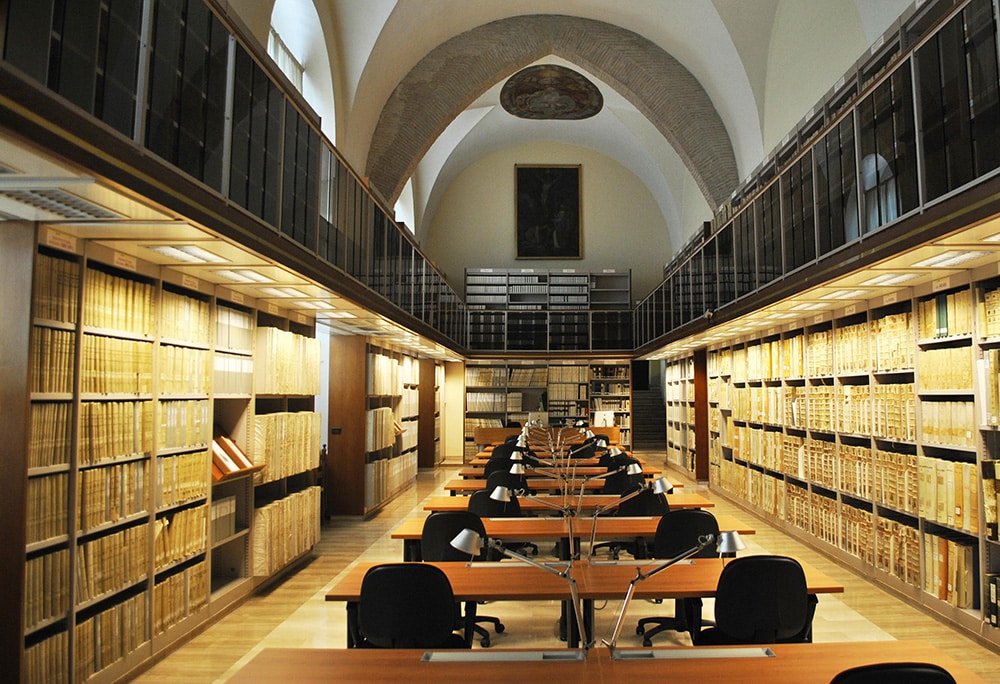

Officially founded in 1612 by Pope Paul V, the Vatican Archives brought together in one place the documents that previously had been scattered in several different locations. But the misfortune was not over, especially resulting from the seizure of the archives ordered by Napoleon in 1810. Nevertheless, the true turning point of the archives’ history came in 1881. Pope Leo XIII opened the Vatican Secret Archives — recently renamed the Vatican Apostolic Archive by Pope Francis — to scholars doing historical research, since, as Leo XIII said, “The Church needs the truth.”

Knights, Crusades and Inquisitions

Since then, there have been numerous discoveries about chapters throughout Church history, even the aforementioned most controversial ones, where Gorny and Rosikin focus their attention.

Years ago, Barbara Frale, an authoritative medievalist, discovered a document called the Chinon Parchment, which sheds light on a dark and misunderstood event: the dissolution of the Knights Templar, one of the richest and most powerful religious orders of the Middle Ages, and the execution of its leaders. In spite of many attempts to put the blame on the reigning pope, Clement V, the parchment gives evidence that the pope found no evidence of the worst charges against the Templars — heresy, desecrating Mass, sodomy — which were spread by the “propaganda machine” of King Philip IV of France, whose goal to dissolve the affluent military order was driven by greed and the desire to take possession of their great wealth for the empty state treasury.

The next chapter is on the Fourth Crusade, ending in 1204 with the Sack of Constantinople, the richest city of the Eastern Christian world. The agreement made between the crusaders — mainly French, Flemish and Venetians — and a pretender to the Byzantine throne was to elevate him in exchange for money and military support in the Holy Land. But after they agreed for him to become emperor, taking the name Alexios IV Angelos, he couldn’t pay what he promised. The city consequently was plundered, and the Latin Empire of Constantinople was installed.

Eastern Christians often cite these painful events as being a source of hatred and division between Catholics and Orthodox, even to the present day. But as the Vatican Archives demonstrate, Pope Innocent III did everything to stop the crusaders, to the point of excommunicating them. “Now the Greeks detest the Latins more than dogs. … You preferred earthly wealth to celestial treasures,” he angrily wrote to the new emperor, Baldwin of Flanders.

The third chapter deals with the “Paradoxes of the Inquisition.” Beyond many black legends, some research stands out: Torture was used in less than 10% of the Inquisition trials, much less than in secular courts, and only 2% of all the trials conducted by the Inquisition ended in death sentences.

‘Not afraid of history’

Pope Paul III’s encyclical Sublimes Deus, published in 1537, marks the first papal document on the native population of America. At that time, the temptation for the Spanish and Portuguese to exploit cheap labor from the native people was very strong, and for this reason, the magisterial text provoked debates on Native Americans’ rights. “They are truly men,” Pope Paul III wrote. This statement may seem obvious today, but it was not five centuries ago. The authors of “Vatican Secret Archives” write that evangelizing those lands put an end to practices such as ritual mass murders. In 1487, the authors write, the Aztecs sacrificed between 21,000 and 84,000 human victims in four days.

Regarding the often misunderstood trial of Galileo and his assertion that Earth was not the center of the universe, the authors report that despite a widespread misconception, the Italian astronomer was charged with a disciplinary offense, not a doctrinal one.

When announcing a year ago his decision to open the archives to consultation by scholars, Pope Francis said that the “Church is not afraid of history.” However, in order to avoid myths and falsifications, there is only one solution — namely, the idea that inspired the authors’ work: “one must first thoroughly and accurately ascertain the facts.”

Deborah Castellano Lubov writes from Rome.