Mental illness has historically been resistant to treatment for a number of reasons. One is simply a lack of understanding. Mental health sources and causes are still largely a mystery to researchers and healthcare professionals. While important progress has been made in recognizing and treating various psychiatric, psychological and behavioral disorders, they are still largely a mystery.

A second barrier to addressing issues related to mental health is the stigma that has historically been associated with mental illness. Terms like “crazy” and “insane”; or the more colloquial “nuts” and “batty” have stigmatized persons with mental illness, causing them to try to keep it to themselves, self-medicate, or even end their lives.

A third impediment to the care for mental health is that many Christians make the grave error of seeing mental illness as rooted in the sin of the person suffering, as though it is a punishment or the “natural” result of sinful behavior. Scientific research is attempting to address the first hurdle. But addressing the others is up to us non-scientific or non-medical professionals. And it is a duty of Christian charity.

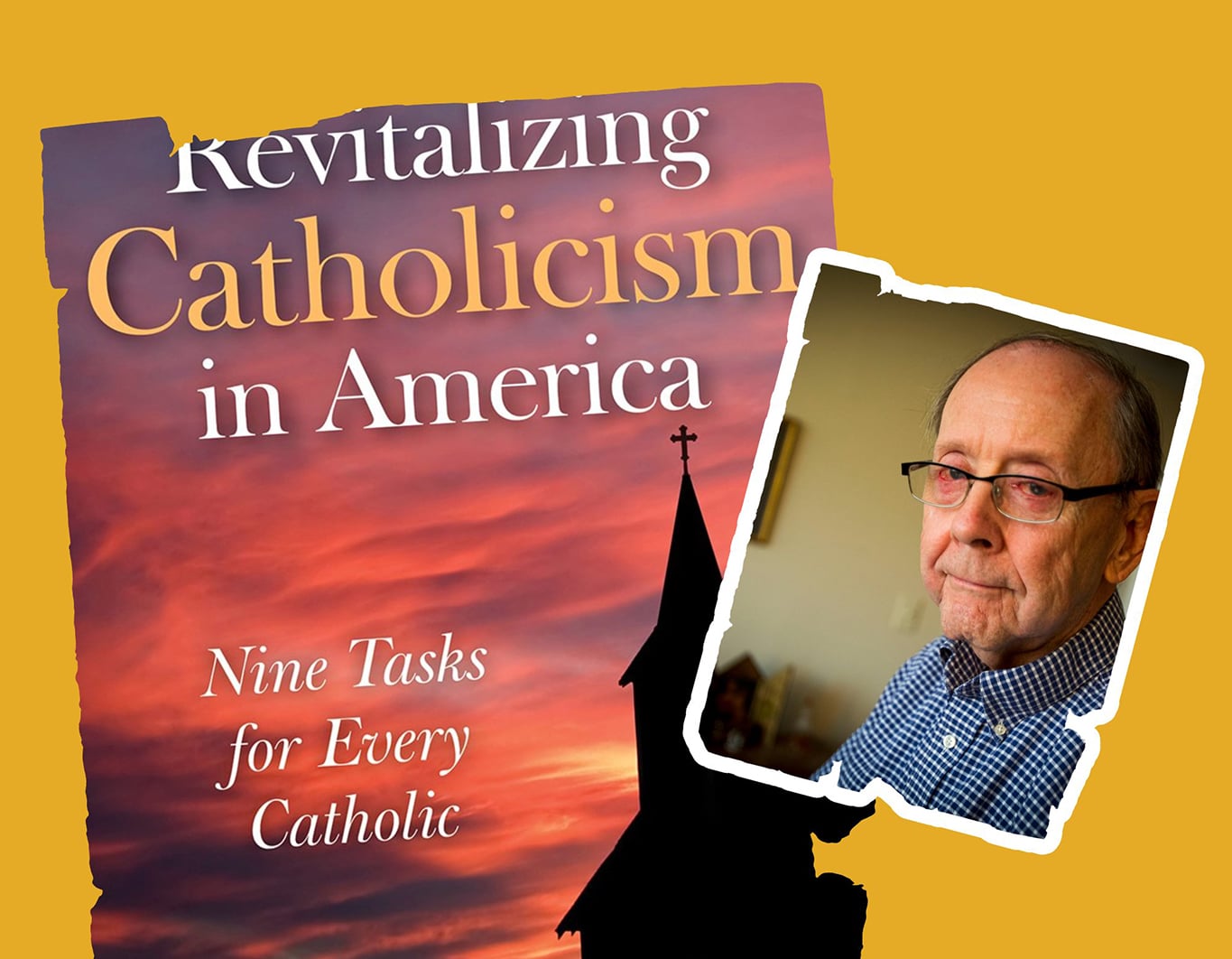

National Catholic Mental Health Campaign

On Oct. 10, the U.S. Catholic Conference of Catholic Bishops announced the National Catholic Mental Health Campaign to address mental illness’s stigma and challenges. The campaign, which commenced on World Mental Health Day, “aims to inspire a national conversation around the topic of mental health and to mobilize the Catholic Church to respond compassionately and effectively to the mental health crisis.” This is an important initiative that we Catholics should embrace and advance.

All of us are broken to some degree. Those diagnosed with mental illness often differ from us “normal” people only in degree, not kind. Don’t get me wrong. I do not intend to deny that psychiatric, psychological, or behavioral disorders are real medical conditions or diseases, no less than diabetes, hypertension and lung disease. However, the symptoms and behaviors accompanying mental illness are often similar to those that we all experience at some time in our lives. We cannot equate the “blues” with depressive disorder, for example.

Nor is nervousness about public speaking, as another example, the same as a generalized anxiety disorder. But we can recognize in ourselves, even if in very mild forms, illnesses and conditions that overwhelm people with those clinical conditions. This ought to engender empathy and solidarity, such that we do not judge others but rather accompany them. Properly situated in the context of a Catholic understanding of the redemptive role of suffering, grace can be communicated through this accompaniment.

Examples from two of my favorite novels help to illustrate my point.

Two beloved fictional examples

Narrated by its central protagonist, Ruthie Stone, Marilynn Robinson’s novel Housekeeping chronicles the redemptive relationship between Ruthie and her mother’s sister, Sylvie Fisher. After teenager Ruthie’s mother commits suicide, Aunt Sylvie comes to their Idaho home to care for Ruthie and her sister, Lucille. Like her deceased sister, Sylvie suffers from some undiagnosed psychological or emotional disorders, perhaps precipitated by their father’s death by drowning in a train and bridge accident when they were children.

Sylvie copes with her illness through elaborately eccentric behaviors that eventually lead to court-ordered intervention by social services. Lucille cannot bear Sylvie’s oddities and moves out of the house to live a “normal” life with a teacher from the local school. But Ruthie will not abandon Sylvie either to the authorities or to Sylvie’s mental illness. Rather, she finds in her aunt a source of serendipity and spontaneity that animate Ruthie’s own life. Through a series of events that draw them ever closer together, Ruthie helps Sylvie manage her illness and stay alive. In turn, Sylvie bears grace to Ruthie through her suffering.

A very similar relationship is illustrated in Walker Percy’s classic novel, The Moviegoer. The novel’s protagonist, Binx Boling, seems to fall into the category I described above–not suffering from mental illness, but clearly on that continuum that sometimes makes the difference between illness and wellness one of degree rather than kind.

Because of his own eccentricities, Binx is the only person in the novel who understands his step-cousin Kate Cutrer, who is considered troubled by her family, but whose probably schizophrenia or major depressive disorder goes undiagnosed. Acting in a way that Kate’s stepmother finds irresponsible, Binx is a healing presence to Kate. In turn, Kate brings stability and constancy to Binx’s life that he otherwise does not possess. Separate, Binx and Kate seem destined for an unhappy if not tragic, ending. Together they forge a relationship that saves them both.

Both Ruthie and Binx meet the challenge of recognizing that Sylvie and Kate do not meet the standard of “normal” behavior. Their responses are not to judge or avoid, like those around them. Rather, they see the dignity of their troubled companions despite their respective illnesses and unite in solidarity with them. As such, both novels teach us something about what the USCCB intends in drawing our attention to mental health issues, to “inspire … solidarity with those suffering from mental health challenges” and “respond with compassion for those who are suffering.”