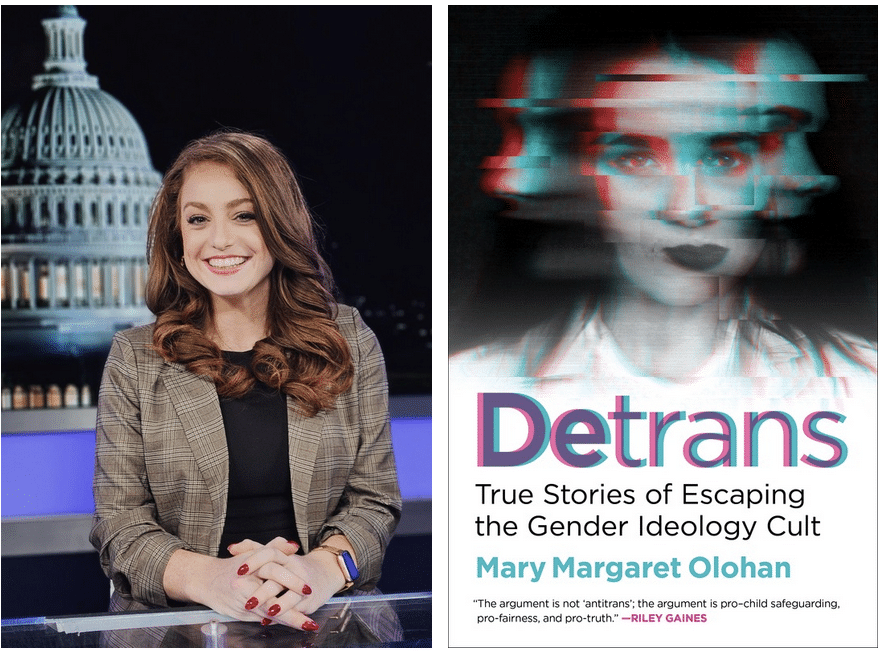

The following excerpt is from Detrans: True Stories Escaping the Gender Ideology Cult, a new book authored by Daily Signal’s senior reporter Mary Margaret Olohan. The book is available for purchase here. The excerpt has been edited for brevity.

Detransitioner. That isn’t a word that often comes up in daily conversation. To my knowledge, spellcheck and dictionaries don’t even fully recognize it yet.

So what does it mean? The word describes a person who has attempted to use surgery or hormonal intervention to change their biology because they believe, or want to believe, or have been told, that they were born in the wrong body. And that nothing will make them happy and content until they have rectified that mistake.

So that person detransitions: They try to reverse the process. They stop taking hormones, they reverse the surgeries (to the extent that that is possible), and they attempt to deal with the mental and physical consequences of such brutal interventions in the physiology and anatomy of the human body.

Not everyone makes it to that point. But my new book “Detrans: True Stories of

Escaping the Gender Ideology Cult” shares stories of those who have and who are brave enough to speak out about their experiences.

What is ‘detransitioning’?

In March 2023 the Associated Press defined detransitioning as “stopping or reversing gender transition, which can include medical treatment or changes in appearance, or both.” Of course, the AP claims that detransitioning is rare. And it is quick to tell readers that the process of detransitioning “does not always include regret” (a laughable claim, considering the circumstances, but one pushed hard by advocacy organizations).

Any examination of mainstream or corporate media coverage of transgender issues will quickly let you in on a secret: Most media is focused on promoting a single narrative when it comes to LGBTQ and gender ideology issues, a narrative heavily informed by the reporting style guides of organizations like GLAAD and the Human Rights Campaign.

GLAAD, formerly known as the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, actively discourages reporting on “negative claims about the transgender community.” The organization also urges reporters to “avoid elevating singular voices or rare cases and concerns in equal weight to overwhelming consensus and preponderance of evidence,” noting that “doing so is inaccurate journalism and storytelling.”

Further, GLAAD offers the media a glossary of terms recommended for reporting on the issue, including the phrase “gender-affirming care.” If it is not immediately clear to you what that phrase means, you aren’t alone. It is purposefully nebulous, artfully positive in tone, successfully vague, an activist umbrella term used to obscure the grisly details of transition procedures such as hormones, puberty blockers, and irreversible surgeries, even for children.

In 2021 alone, about 42,000 children and teens across the United States received a gender dysphoria diagnosis … almost double the number of gender dysphoria diagnoses from 2020 (24,847).

This “gender-affirming care” language has been widely embraced by non-conservative media outlets, including outlets with massive reach, such as CNN, the Washington Post, and the Associated Press.

The use of the phrase has become so standard in coverage of legislation banning irreversible sex-change surgeries and hormones for minors that it is almost impossible for the average reader to know what is being banned, particularly if they are not already familiar with “gender-affirming care.”

“Gender-affirming care is medical care,” claimed Rachel Levine, a male who serves as the assistant secretary for health for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “It is mental health care. It is suicide prevention care. It improves quality of life, and it saves lives. It is based on decades of study. It is a well-established medical practice.”

A publication from the Biden administration’s Office of Population Affairs, released in March 2022, emphasized that “for transgender and nonbinary children and adolescents, early gender-affirming care is crucial to overall health and well-being.”

Why? Because this “care,” which the messaging acknowledges may include top surgery (to remove or create breasts), bottom surgery (surgery on a girl’s reproductive parts or on a boy’s genitals), and facial feminization surgeries (surgery to restructure a boy’s face into something more feminine), allegedly “allows the child or adolescent to focus on social transitions and can increase their confidence while navigating the healthcare system.”

Turning back

In 2021 alone, about 42,000 children and teens across the United States received a gender dysphoria diagnosis, according to data compiled by Komodo for Reuters, almost double the number of gender dysphoria diagnoses from 2020 (24,847). Between 2017 and 2021, a total of at least 121,882 children between the ages of six and seventeen were diagnosed with gender dysphoria.

These numbers are alarming. And yet, more and more men and women are stepping forward to speak up: to reveal that they, too, were persuaded to attempt crossing that unfathomable divide, that of changing one’s sex.

And then they realized they had been lied to, and they turned back.

Every detransitioner has a unique story. But many of the same fact patterns are present in their stories. These fact patterns often, though not always, include an unhappy childhood or an adolescence fraught with abuse or loneliness. Gender dysphoria at a young age. Discomfort in their own body. Struggles to make friends. Signs that they were on the autism spectrum (often without the confirmation of a medical diagnosis). Adults in their lives, often on the internet, in LGBTQ circles and chat rooms, who pushed them towards transition, hormones and eventually surgeries.

This is Prisha’s story.

Prisha Mosley

Prisha Mosley was attending a high school in rural North Carolina at the time (a “really bad” school, she told me, with unprofessional teachers and badly behaved students). As she matured, Prisha began to be more and more self-conscious about her breasts, which she said were quite large, drawing inappropriate attention from her peers.

She was touched inappropriately “pretty much every day,” she said.

At fourteen years old, she told me, Prisha was raped by an adult. And that rape caused her to become pregnant.

Prisha’s body couldn’t sustain the pregnancy. She was grappling intensely with a crippling eating disorder. The young girl, still reeling from her assault and the knowledge that she was pregnant, found herself miscarrying her infant child.

The miscarriage of her baby was graphic, Prisha told me. She was not only taken unawares–she was distraught.

“I lost the baby because I couldn’t eat,” she would say. “I had failed as a woman, my body a graveyard. …”

“I was so young and ignorant that I thought [rape] only happened to girls,” she explained to me. “I wouldn’t talk about it. … I feel like [the therapists] should have seen that as a red flag too, but they didn’t.”

At age seventeen, she began testosterone injections. And at age eighteen, she went under the knife to remove her breasts. Forever.

She cried as she shared the story with me. I asked her if she had ever named the baby. Yes, she said, she had named her baby June.

Realization

Prisha had gotten her long-awaited surgery.

Things were supposed to be better. But they weren’t.

“Did you have a moment of realization there, when you just knew?” I asked her.

“I did,” she said. “I kept it secret for like a year, a year and a half, because I felt ashamed and like I had invested so much in being trans and I couldn’t go back, and like…my family wouldn’t accept it.”

She quit taking testosterone “cold turkey.”

When Prisha stopped taking testosterone, the anger and rage that she had been feeling largely receded. She felt like she was able to “think more clearly,” to connect with her emotions again. “I was able to cry,” she told me. Huge.

“I really feel like the testosterone just kind of made me dumber,” she insisted. When I asked her to clarify this a little more, she explained that she felt “emotionally dumber,” and “not as emotionally intelligent,” unable to articulate the deep, consuming emotions she was feeling.

Now she is back to normal, Prisha told me, and she feels in touch with her emotions again. She elaborated that testosterone hadn’t stripped away her empathy, but it had made it harder for her to identify the emotions that she was feeling. She recalled moments where she struggled to put a finger on the cause of her inner turmoil, asking herself in bewilderment, “Am I angry? Am I sad? Am I hungry? I have no idea what’s going on, I just feel bad. …

I kept it secret for like a year, a year and a half, because I felt ashamed and like I had invested so much in being trans and I couldn’t go back, and like … my family wouldn’t accept it.

Prisha Mosley

“I’m more cognitive, more clearheaded, more calm, soothed, I guess. Just generally better.

“And I can cry,” she said again.

Lingering pain

She used to be so proud of her ability to sing. Now she can’t. “I believed that my voice would even out,” Prisha told me, “because I was told over and over I would have just as good of a voice, but in a male range. Instead, I have a crushed larynx. I have no volume, it hurts to sing, and it hurts to talk for long periods.”

The testosterone also affected her sexuality and preferences in a potential mate, she came to realize. “It made me bisexual,” Prisha said. “Which I feel weird about … it just made me like … horny all the time. And just care less about who my partner was.

“That sounds awful,” she added. “I’m a very emotional person and I think that sex is for intimacy. But my body was not on the same page, you know what I mean?”

“So it was more like the person mattered less and the physicality mattered more?” I asked her, to which she agreed, “Yeah.”

“I just wanted it more often. I lost genital preference. I just wanted it to feel good.”

Throughout our conversations, Prisha often apologized for being frank. “I’m sorry for being vulgar,” she told me at this point. And as I had before, I told her that her openness would help others understand the truth of what she had been through.

As she stopped the testosterone, she told me, all the negative side effects that she had experienced were decreasing. “My body temperature has changed. I don’t feel like I’m on fire anymore, which is pleasant.

My neck and my shoulders literally burn all the time, like I can’t hold them up or something, like they’re too big for my frame, they literally always burn.

— Prisha Mosley

“I was hot all the time on the testosterone,” she added. “Unfortunately my shoulders grew a lot and I lost some of my hair and I gained hair on my face and my body. And my feet grew. None of that was going to change.” But now her hair is shinier, she told me with relief. Her skin is softer. Little things like that, she said, are more feminine.

Prisha’s eating disorder was so severe that it kept her from finishing puberty before she began taking testosterone and undergoing her surgery. She thinks that because of this, her experience may be similar to that of a child who is put on puberty blockers–“I had big changes,” she reflects.

She’s had chronic, burning pain in her neck and her shoulders since being on and especially since stopping the testosterone. Prisha told me she’s pretty sure this pain is linked to the fact that her body had not finished going through puberty when it was pumped full of hormones. “I’ve heard that from other women who have been on testosterone and transitioned,” she told. “My neck and my shoulders literally burn all the time, like I can’t hold them up or something, like they’re too big for my frame, they literally always burn.”

She described the sensation as similar to the burn that comes from working out. “It’s like that. All the time.” And she isn’t sure how to fix it other than going to the chiropractor or getting massages. “I can’t make the rest of my body grow bigger to fix it,” she said. “I’m out of puberty.

“There’s no cure,” she said. “I can kind of … fix the symptoms.”

And there are no doctors brave enough to offer her their help.

Regret

I asked Prisha if there was a point where she suddenly regretted her mastectomy. She didn’t recall an exact moment, but she said that she began having “phantom breast syndrome” about eight months to a year after the surgery. “And that’s when it started setting in really hard,” she said. “I was in really deep denial. I was just like, ‘This is the price I have to pay to not be suicidal.’ The feeling of [the phantom breasts] was less severe than the suicidal feelings so I was like, ‘I can take it,’ you know?”

Multiple detransitioners have told me that they aggressively used drugs and alcohol when they were beginning to detransition. Prisha told me that she was “stone-cold sober” when she was detransitioning, at first in secret. But she smoked a lot of weed and meditated in attempts to slow down and “not be frantic.”

She added, “I’m being actively cautious to not overdrink or overuse.”

She had poured all her resources, mental and physical, into this transition attempt. And at that point, she didn’t know what to do. Do I cut my losses and take zero? she thought to herself.

Prisha did share that she has cut herself a few times since detransitioning, to the point where she needed stitches.

But she is a lot more at peace now. “I feel like I’m not really fighting as hard anymore to try and be something that I’m not and try to ‘be in the right body’ anymore,” she shared. “I’m trying to accept my body and appreciate it rather than change it.

“Changing it is like anguish. I was really actively putting energy into hating myself and my body,” she said. “And not doing that is saving me and bringing me peace.”

Reclaiming her identity

She has struggled with her relationship with her parents. When I first spoke to her, Prisha had not seen them in a long time, and she was upset that her mother was receiving hate online from Prisha’s old transgender-promoting support group.

“I’ve already put my mom through so much,” an emotional Prisha tweeted in April 2023, “she bathed me when I couldn’t move my arms after my mastectomy … she was told if I killed myself it would be her fault … she didn’t deserve it. Now she’s being harassed by my old trans support group and it is more pain for her. …”

In June 2023, Prisha finally made the decision to go see her parents again. She hadn’t seen them in seven years, she said. And she shared a little bit of her journey on social media: “I’ve arrived. My mom picked me up. She brought me to their house and we ate. I got to talk alone with my dad after he dropped me off at the hotel. I’m here now, and my parents are at their house to take a nap. A lot of emotions, and I’m exhausted too.”

But the main thing that has helped Prisha to ground herself, focus on the future, and accept her femininity is the daughter of the man that she loves.

She told me that she grieves over her miscarried baby, June, to this very day. “I’ve even struggled with phantom pregnancies,” she said. “I just wish that I could get pregnant now,” she told me tearfully, “and have a body for that soul to go into.”

Her boyfriend’s daughter is the reason for her social detransition, Prisha shared. “He has a three-year-old daughter, and she calls me mom,” Prisha said. “She clocks me as a woman, and I fall into that role with her, and everything is very motherly and feminine, and I’m not a father at all, not like the big protector, I’m the nurturer and the carer. …

“It’s amazing,” she said simply.

Though she initially “medically detransitioned” by stopping her testosterone injections (“I stopped poisoning myself,” she said somewhat sarcastically), she continued to live, act and dress like a man for a while. She also had a bit of a beard at this point, and she wasn’t shaving. “I was too deep in the shame and the lie,” she said. “I was like, well, I’ve uprooted my entire life and everybody else’s for this. I have to live with it.”

She had poured all her resources, mental and physical, into this transition attempt. And at that point, she didn’t know what to do. Do I cut my losses and take zero? she thought to herself. Or do I continue to hemorrhage everything I own for the rest of my life until I die?

| GENDER IDEOLOGY |

|---|

|

“Detrans: True Stories of Escaping the Gender Ideology Cult” (Regnery, $32.99) by Mary Margaret Olohan is a compelling book that gives voice to detransitioners–individuals who regret their gender transition and have reverted to their original gender. Through in-depth personal interviews, Olohan presents the stories of detransitioners who were once caught up in the fervor of gender ideology. These testimonies reveal the emotional and physical scars left by manipulative therapy, botched surgeries, and toxic online communities. The book highlights the complexity and pain often ignored during “Gay Pride Month” celebrations, which now encompass transitioning as well. The number of young people convinced they were born in the wrong body has surged, spurred on by activists, educators, and even medical professionals. Despite media portrayals of transitioning as a happy ending, “Detrans” unveils the harsh reality faced by detransitioners. These individuals, once embraced by the transgender community, are now silenced. Their lawsuits against those who treated them underscore the serious consequences of hasty gender-affirming interventions. Olohan’s work exposes the disturbing truth that transgender activists seek to hide, making “Detrans” an indispensable piece of evidence against the unchecked power of gender ideology. |

She began dating her boyfriend, Prisha says, and he eventually trusted her enough to bring his daughter around her. “She was about 2 at the time,” Prisha reminisced. “And despite all that stuff I said about living as a man and literally having a beard, she started to call me ‘Mommy.’ And then I was like, ‘That’s it. I know exactly what I want. Anything is worth getting that which I have just had a taste of.'”

“Do you remember the first time she called you ‘Mommy’?” I asked.

“Yeah, yeah, I remember it clearly,” Prisha said eagerly. “I was sitting on the couch and she was standing up and she looked at me and she said it with her arms extended towards me.”

When I asked her what she felt in that moment, she responded: “Disbelief. Shock. Wonder. Amazement. A little bit of terror, maybe of responsibility. And the weight of love. But mostly love. …

“And it’s been like that ever since.”

Copyright © 2024 Mary Margaret Olohan. Excerpted by permission of Skyhorse Publishing Inc.