During the summer of 2018, the Church in the United States was devastated by revelations of sexual abuse and the subsequent deluge of allegations, the likes of which had not been seen since the “Long Lent” of 2002 in the wake of the Boston Globe’s investigations.

Between the report of “credible and substantiated” accusations made against then-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, as well as the many claims that would be made in the following weeks, and the report of the Pennsylvania grand jury regarding the handling of abuse accusations by dioceses across the state, the Church was drowning with this millstone hanging about its neck.

It is no secret, nor any surprise, that the laity have felt betrayed by these revelations. Many are asking questions such as: “How did this happen? How did McCarrick advance so far and become so influential, when ‘everybody knew’? How did these bishops continue to move around and enable serial abusers? Why, Lord, did you let this happen?”

Some commentators have (in broad terms) observed that the scandals that broke in 2002 were largely issues of misbehavior by priests, whereas the 2018 scandals are more markedly betrayals on the part of bishops. This has also left many faithful priests feeling abandoned, betrayed and heartbroken. But, by a great grace, it has also strengthened the resolve of many priests to be holy — and for this we give thanks. For it’s more obvious than ever before that the Church needs holy and faithful priests.

Paul Senz writes from Oregon.

Saints, arise

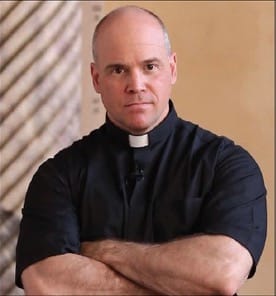

“Along with the rest of the world, I was left with many questions and had to wrestle with a slew of emotions” following the revelations of abuse this summer, said Father Stephen Gadberry, a priest of the Diocese of Little Rock, Arkansas. “I have felt anger, confusion, betrayal, fear and numbness. I am frustrated that individuals would make such decisions to abuse and hurt the most innocent, and just as much aggravated that others would intentionally cover up such scandalous acts.”

Ordained in 2016, Father Gadberry grew up in a simple, German Catholic family on a farm in the Arkansas Delta. His faith was deepened and became more personal during a stint in the U.S. Air Force following high school.

“My Catholic identity was no longer simply something I did,” he said, “but it was beginning to truly shape who I was.” A handful of military chaplains and Catholic families nurtured his faith, and after leaving the Air Force, he entered the seminary.

The scandals of 2002 did not personally shake Father Gadberry. “Although it was a challenging time as a Catholic, I was too ignorant of the reality to be affected positively or negatively,” he said.

This year has been different. No longer a Catholic whose faith plays a fairly minor role in his life, he is now a priest in the midst of a major crisis of trust in the structures of the Church.

“In the face of this strife, from within and without, one is forced to question their modus operandi,” he said. “This is a time when saints arise and the fainthearted are swept away.”

Although he has never doubted his priestly vocation, Father Gadberry believes he has been invited by the Lord into a deeper level of trust and more faithful discipleship. This is necessary when faced with the sorts of questions he is faced with.

“I have to question my intentions. I have to question my personal life. I have to question my public life. It is certainly a moment of personal purification when my faith is being forged to a new degree of steadfastness,” Father Gadberry said.

There have been signs of encouragement and hope, not to mention peace, through these turbulent times. The bishop of Little Rock, Bishop Anthony Taylor, has been proactive and outspoken in his response to the crisis. And the faithful in the pews have shown their fidelity.

“I have witnessed so many embrace their faith and express their pride in being Catholic,” Father Gadberry said. “Saints are truly coming to the forefront.”

This has encouraged Father Gadberry in his own faith and vocation. “I proudly wear my clerics and live my faith around town,” he said. “I encourage the parishioners to proudly wear their faith, too.”

The priests of the Diocese of Little Rock, and many others across the country, have had several meetings together over recent months, prayer vigils with the bishop, and hours of open dialogue with the bishop and other diocesan officials.

“The scandals of sin can lead anyone down one of two paths: sin or holiness,” he said. “The shortfalls of the priests and bishops have shown me in a new way the scandal of sin and the hurt that ensues. Through this, I have better learned to discern the needs of my flock. It has challenged me to help the faithful embrace their humanity, but more so, to embrace Christ.

“I would encourage brother priests and the faithful to stay focused on Christ above all else,” he said. “The ship may be rocking, but it will not sink.”

Protecting the people

In 2002, Father Alek Schrenk, a priest of the Diocese of Pittsburgh, was in the seventh grade — old enough to remember, but not quite old enough to really understand the significance of what was happening as the clergy abuse scandal broke. Father Schrenk attended a single parish all throughout childhood and the scandals never hit close to home.

“All the priests I had ever known were good men,” he said, “and their names were never implicated in any of the reports, either then or now.”

But there was a sense that something was different. “The most I remember was a sense of suspicion or malaise during those years.”

Once, when Father Schrenk served a funeral during the middle of the school day, the priest, who had another commitment, asked him to lock up the church. Upon returning to class, “my teacher looked concerned that I had come back late. She took me aside after class and asked me if anything had ‘happened.’ I was floored by the suggestion that there would have been any threat to me by our priest.” This shadow of suspicion marked Father Schrenk’s experience of the scandals, and sticks with him even today.

Father Schrenk was ordained a priest for Pittsburgh in June 2017, so his priestly life is still quite young. He began to feel called to the priesthood during college at Duquesne University. A spiritual direction relationship with a priest on campus helped Father Schrenk to reframe his vocational question from “What do I want to do with my life?” to “What is God calling me to do with my life?”

“For whatever reason, after making the decision to discern, I always had a high degree of personal certainty that God was calling me to be a priest,” Father Schrenk said. “There was something thrilling about the idea of going ‘all in’ for God, and doing something that was totally unconventional.”

As a priest of the Diocese of Pittsburgh, Father Schrenk was particularly and personally floored by the Pennsylvania Grand Jury report this summer. The details of the cases and the accusations were a bombshell, harrowing and humiliating.

“It still boggles my mind that anyone, let alone a priest, would be capable of those sorts of things, and against minors,” he said. The sense of outrage was deepened by the McCarrick scandal, which was unfolding at the same time.

“It’s the scandal of Archbishop McCarrick that clarified my sense of betrayal more than the grand jury findings, but the two worked off each other, contributing to a sense that while 2002 might have been about priests, this year’s scandal is a moment of reckoning for our bishops,” he said.

This sense was confirmed by his parishioners. He received nothing but support from those who also shared with him their sense of disillusionment and disappointment with the Church’s leaders.

Now, a few months after the report’s findings were made public, he says he has reached a sort of “mental and spiritual equilibrium.” And he refuses to let it affect his vocation or ministry as a priest.

“If I’ve had one takeaway from all of this, it’s that the world, and my diocese in particular, needs good and holy priests now more than ever,” he said. “I see that as an integral part of my vocation, and I pray to God that I can do my part to restore people’s trust in the Church. I don’t know a single member of the junior clergy in my diocese that doesn’t feel the same way.”

For Father Schrenk, the most challenging moment of the scandals was having to preach about them. Based on conversations with parishioners, some seemed to have a very superficial understanding of things, others thought the Church was being targeted, and others were feeling deeply wounded and disillusioned, while still others seemed not even to have registered any of it. Tackling the issues many times throughout the summer, his homilies were received well, but “it was never easy standing in front of people who had come to church, presumably for a moment of spiritual refreshment, and having the sense that I was burdening them with more reminders about the scandals,” he said. But in reality, he thinks people were grateful to hear these things addressed frankly from the pulpit.

One particular moment of encouragement happened after Mass this summer, shortly after the Grand Jury findings were released. A woman came up to him at the door of the church, took his hands, looked into his eyes, and said, “We’ll get through this.”

“Those words meant the world to me and still do, because I believe her,” he said.

Father Schrenk believes that these scandals can be a darkness that makes the true light of the Church shine all the brighter. His generation of priests grew up in a Church marked by these scandals, and they chose priesthood anyway; so, in a sense, they operate apart from the scandals.

“There’s no sense of suspicion that we knew anything — rumors about a brother priest, a sense of inbred clerical culture, for example,” he said. “The culture of diocesan priesthood is changing. It’s still a brotherhood, but we’re not going to endanger or harm our people in order to protect ourselves. I think that people need to see that priests are united, strong in their faith, and dedicated to holding each other accountable.”

Most of all, he said, people need to know that priests are on their side.

‘500 years of saints’

“The scandalous crimes that were revealed in 2002 were a watershed event, I believe, not just for myself, but for all priests, indeed for the whole Church,” said Father Steve Grunow. A priest of the Archdiocese of Chicago, Father Grunow is now residing in Santa Barbara, California, as he is the CEO and executive producer for Word on Fire Catholic Ministries, with Bishop Robert Barron. Father Grunow was ordained a priest in 1997 and has seen the Church in the United States suffer through scandal for most of his priesthood.

In 2002, as the extent of the horrible crimes was revealed, “we all watched as a mask of virtuous unrealities and pious pretense slipped off and behind that mask was revealed a howling visage of diabolical evil and human stupidity,” he said.

Never one to forget that the Church is peopled with sinners, no less so among the clergy, the scope of the crimes and the violation of the innocent was still shattering. The dreadful way in which the crimes were handled seemed antithetical to disciples of Jesus. “I could not, and still cannot, understand the rationale that justified the approach that had been taken to these crimes,” Father Grunow said.

The result of all this for Father Grunow, on a very personal level, was “an Abrahamic decision to move forward with only an act of faith to guide myself through a deep darkness,” he said. He was resolved to proclaim the beauty, goodness and truth of the Church, “which is under constant attack by devilish plotting and human iniquity.” The cure for this darkness is the light of Christ.

The scandals that broke this summer were like a horror movie plot that turns out to be true, he noted.

“The impact of these crimes will be a reality of the Church’s life for some time. Indeed, it will take 500 years of saints to restore the Church’s credibility.” Each incident of sexual abuse reaches out from the victim in a kind of ripple effect through their family, friends and communities, that encompasses hundreds or thousands of people.

“The devastation and destruction unleashed by this crime is diabolical in its scope, thus the absolute urgency of coming to terms with the historical realities and making sure that any incident of abuse is dealt with forthrightly.”

The case of Archbishop McCarrick complicates the whole question, as he was himself an architect of the so-called Dallas Charter adopted by the bishops of the United States to govern the handling of abuse cases involving a priest.

“Does McCarrick’s involvement in the development of the Dallas Charter explain the lacuna in regards to how allegations against bishops would be dealt with?” he asked. “The scandal is escalating with the credibility of the Church’s hierarchy in shambles.”

The McCarrick issue prompts some important questions from Father Grunow. He asks “how a narcissist and possibly a sociopath was enabled to advance into the highest echelons of the hierarchy and what can be done to prevent such types from advancing in the future.” This is a major problem of credibility and trust.

“The damage to the credibility of the hierarchy is no small thing as it undermines the work of the Church in every way,” Father Grunow said. “It also leads to a diabolical scattering of the faithful.”

Priests lost their moral authority following the 2002 scandal, he said. As a result of this summer’s revelations, this has all been exacerbated. Many people don’t even see the priesthood as a credible or realistic way of life. And being a Catholic is associated with living in association or even acceptance of terrible corruption.

“A Church that is struggling already with attrition finds itself in an even more difficult situation vis a vis the missionary mandate of the Gospel.”

“I do think that it is absolutely necessary that the bishops work with the laity in regard to the scandals that have enveloped us or the darkness will continue to overtake the Church, and we will remain behind, rather than ahead of, these crimes,” Father Grunow said.

As the CEO of Word on Fire Ministries, Father Grunow is no stranger to the powerful effect that videos and social media can have, and what remarkable tools they are in the New Evangelization. But he stresses that “credibility will not come from videos, or a post on social media, or policies or procedures. Credibility will only come from saints — and this is the hard way the Church seems called by the Lord to go,” he said.

Don’t run from humanity

Father Damian Ference is a priest of the Diocese of Cleveland, currently pursuing his doctorate in philosophy at the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas in Rome. He was ordained a priest in 2003, in the wake of the revelations and scandal that broke with the Boston Globe’s reporting in 2002.

A few months later, allegations began to break in his own diocese, just months before his ordination.

Diocese of Cleveland

“I wouldn’t say that it affected my faith in Christ or in the Church he founded, but it did make it hard to be excited about becoming a priest under a grave shadow of suspicion,” Father Ference said.

He found comfort in a line from a letter of Flannery O’Connor:

“The Church is founded on Peter who denied Christ three times and couldn’t walk on water by himself.”

Living in Rome now, thinking of this quote as he walks past St. Peter’s Basilica, Father Ference remembers what God can do with a sinner like Peter, which is like all of us.

The revelations of this summer “made me mad,” he said. Thinking we had addressed these issues in the aftermath of the scandal in 2002, “obviously, as the McCarrick case has shown, there are still a lot of things lurking in the dark that must be brought into the light for purification.”

How to be a good priest in light of all of this? “A good priest is a human priest,” Father Ference said. “He is someone who understands that before he is a priest, he is first a man. A priest who attempts to run from his humanity, rather than allowing Christ to redeem his humanity, is a priest who is in grave danger.”

Father Ference suggested that priests, bishops, cardinals — all people — need to be honest with themselves and at least one other person.

“The devil wants us to keep our struggles to ourselves,” he said, “and he makes us think that others would think less of us if we shared our weaknesses, which is a lie from the pits of hell. Remember, the devil is the father of lies, and his mission is to keep us in the dark and away from the light of Christ, which brings us healing and freedom.”