Remembrance is a central part of our Catholic faith.

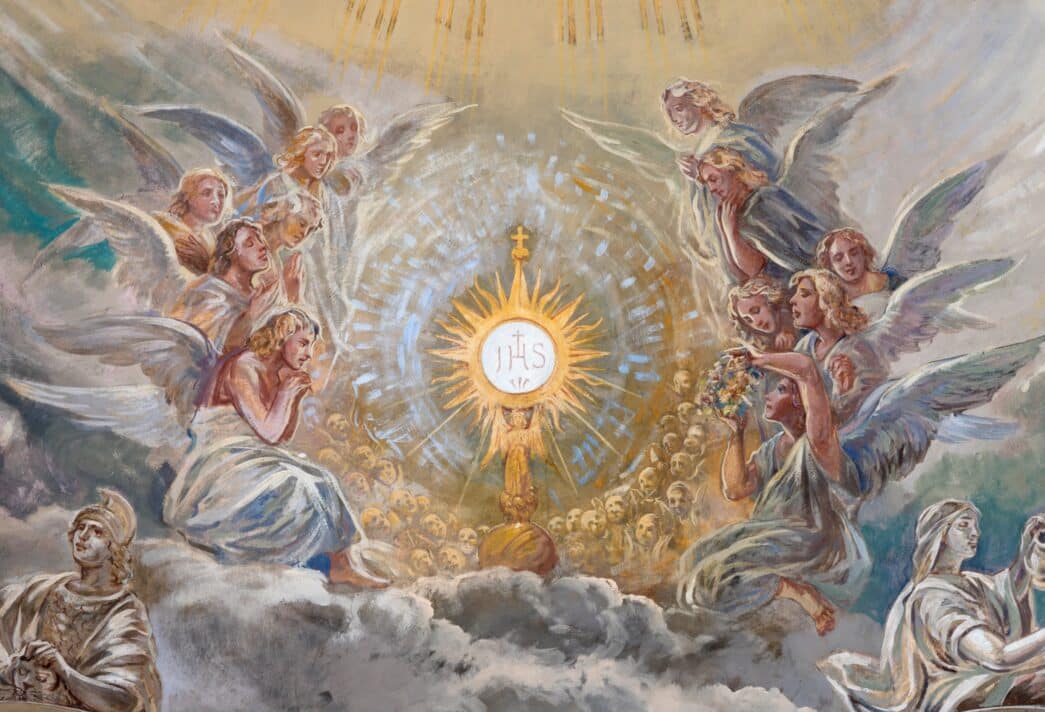

For the nine years I attended Catholic grade school, Friday afternoons of Lent were spent in church. The entire school community gathered to pray the Stations of the Cross, led by the pastor. Stations always ended for us with exposition of the Blessed Sacrament and Benediction.

Over the years, I’ve often thought about how we concluded Stations with Eucharistic worship, and it’s been on my mind a bit this Lent. The connection seems quite fitting.

The Stations are an opportunity for us to remember what Jesus did for us in a precise and specific way. Our meditation on his passion and death — traditionally following along from his condemnation to death to his burial — offers us the opportunity to enter a bit more fully into his experience.

For me, ending the Stations with Eucharistic worship provided the means for making the Stations more fruitful. Having remembered and prayed intensely through reflections on the Lord’s passion and death, being in his sacramental presence offered the opportunity to make the experience more fruitful and, in a sense, real.

This prayerful and focused way of remembering is a central aspect of Judeo-Christian spirituality. The technical term “anamnesis,” or memorial, conveys this reality and is a central component of our Eucharistic worship. Ultimately, it’s a mystery made present by the Holy Spirit.

Something of an art

This biblical sense of memorial, the catechism says, “is not merely the recollection of past events but the proclamation of the mighty works wrought by God for men” (No. 1363). This sense of “memorial,” in the context of liturgical celebration, makes the events of our salvation “present and real.”

The catechism continues: “This is how Israel understands its liberation from Egypt: every time Passover is celebrated, the Exodus events are made present to the memory of believers so that they may conform their lives to them. In the New Testament, the memorial takes on new meaning. When the Church celebrates the Eucharist, she commemorates Christ’s Passover, and it is made present the sacrifice Christ offered once for all on the cross remains ever present. ‘As often as the sacrifice of the Cross by which ‘Christ our Pasch has been sacrificed’ is celebrated on the altar, the work of our redemption is carried out.'”

Remembering is something of an art, and, as a society, it sometimes seems like we have forgotten more than remembered. With our faith’s insistence on its importance, we should consider anew how to remember better.

A means of remembering during Lent

In addition to the Stations ending with Benediction, I think of a lot of other activities from my early years — not all that long ago! — centered around remembering. Having Masses offered for loved ones or visiting cemeteries as a family. Researching family history with my grandpas. Looking at old family photos with my grandmas. Having them tell me stories about their parents and grandparents or drive me past places they once lived or went to school. The list goes on.

And I’m so grateful I learned how to remember like this. These were sacred occasions that not only brought me into contact with the past, but, in a sense, helped me remember who I am. These are things I try to keep alive for my own kids, unusual as they might be in our own day.

So, for Lent, I’m trying to pray the Stations of the Cross more often as a means of remembering. And I believe this remembering will help me to appreciate more fully and enter more deeply one of the core realities of the Mass — the depth of Christ’s love manifested in his passion and death. Doing so can help us to remember, not only who we truly are and what we are called to be, but to be Eucharistic people.