As he neared death, the great Catholic filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock once remarked, “One never knows the ending. One has to die to know exactly what happens after death, although Catholics have their hopes.”

I tend to believe that a person’s last words are very revealing.

Some last words are amusing. Take the 18th-century French composer Jean-Philippe Rameau, who rebuked the priest giving him his final sacraments, saying: “What the devil do you mean to sing to me, priest? You are out of tune.”

Oscar Wilde, too, gave us humor in his final moments: “This wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. Either it goes, or I do.”

And when comedian Bob Hope’s wife, Dolores, asked him where he wanted to be buried, he replied, “Surprise me.”

But not all last words are lighthearted. Some are tragic. Think of John Adams, who bitterly cried out, “Jefferson lives” unaware that his nemesis had died hundreds of miles away that same day.

Other last words are more provocative, more striking, giving us a glimpse of the soul’s reckoning with the mystery of death. Steve Jobs, according to his sister, uttered in awe, “Oh wow. Oh wow. Oh wow,” leaving us to wonder what he saw in his final moments.

Saints have their own unique final utterances, often testifying to the mystery of life beyond. St. Elizabeth of the Trinity said, “I am going to the light, to love, to life!” And then there is St. Catherine of Siena, who cried out with passion, “The Blood! The Blood!” — a powerful expression of her mystical devotion to Christ’s sacrifice. And, perhaps most moving of all, were the final words of Pope Benedict XVI: “Lord, I love you.” How I hope that my own dying breath might carry such a sentiment!

But the final words of a dying loved one are the most precious. They burn themselves into our memory; they are a summary, a final testament to us who are left behind. When we recall them at our moments of trial, they give strength, and as we are seeking, they give direction. My own grandmother, dying of cancer, awoke for a last few moments with her sons. She asked for a beer (and she drank it). She told them she loved them and then gently fell asleep.

St. Francis’ example of renunciation

This leads us to our beloved brother Francis of Assisi, whose memory we keep today. He lived as a “holy fool” for God, famously embracing radical poverty and humility. In a moment of dramatic renunciation, Francis stood naked before a bishop in Assisi, handing his clothes and money back to his father. It was a symbolic act, stripping himself before God, to live fully in his service. Vulnerable and free, Francis renounced everything, everything except his love for Christ.

Francis’s love for Jesus Crucified was so complete that he received, 800 years ago, the stigmata — the miraculous marks of Christ’s suffering imprinted on his own body. This wound of love reflected his deep union with the Crucified Lord. As Pope Francis once prayed, “May our wounds be healed by the heart of Christ to become, like Francis, witnesses of Christ’s mercy, which continues to heal and renew the life of those who seek Him with a sincere heart.”

It was this same love — this love of Jesus Crucified — that gave meaning to all the suffering Francis endured, including the suffering of his death. And it is that same love, by God’s grace, that will sustain us in our own final hour.

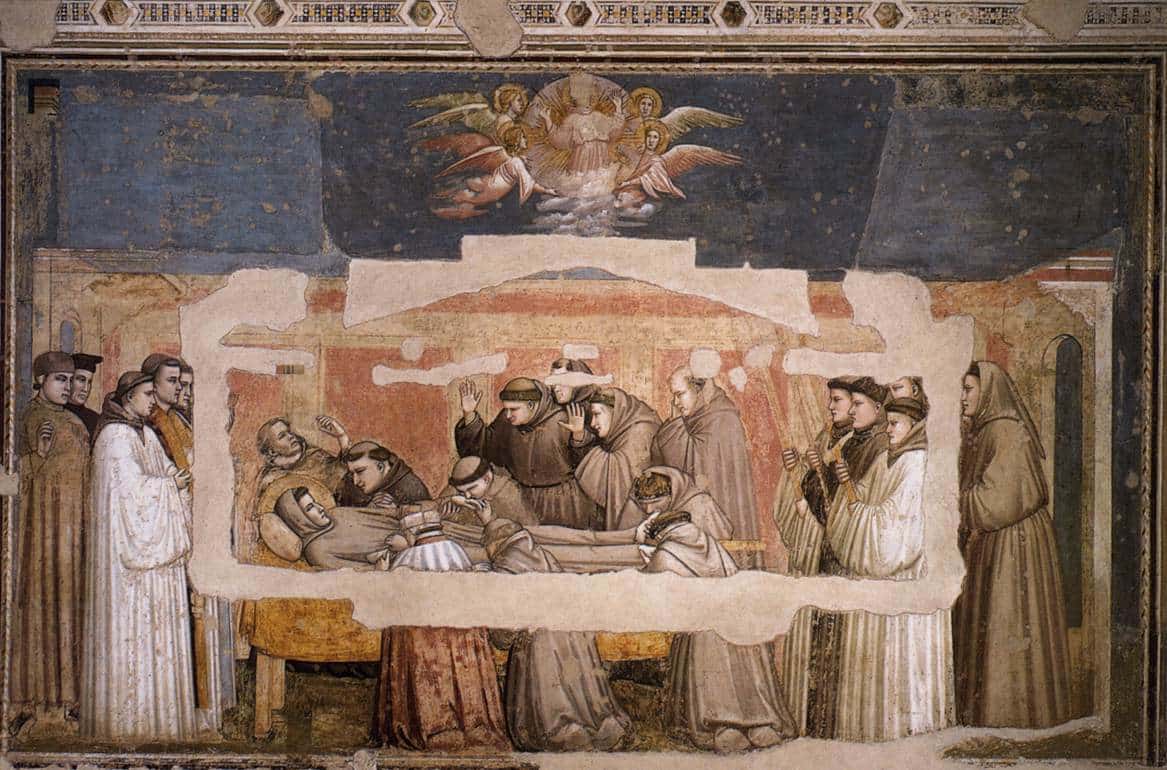

When Francis approached death, he remained true to his radical and complete devotion to our Lord. He asked to be stripped of his clothing once more, dying as he had lived, with nothing — just like his beloved Christ Crucified. He wished to pass from this life with not even a robe on his back, a final testament to his radical love of Christ and his detachment from worldly things.

Each of us will one day stand bare before the Lord. We will be judged not by our possessions, our titles, or our earthly achievements, but by the love we have given and received. As Francis wrote, “In that love which is God, I entreat all my friars, ministers and subjects, to put away every attachment, all care and solicitude, and serve, love, honor, and adore our Lord and God with a pure heart and mind.” In the end, our lives will be measured by love–nothing more, nothing less.

Facing the reality of death

As the Catechism teaches: “Our lives are measured by time, in the course of which we change, grow old and, as with all living beings on earth, death seems like the normal end of life. That aspect of death lends urgency to our lives: remembering our mortality helps us realize that we have only a limited time in which to bring our lives to fulfillment” (No. 1007).

Death is indeed a difficult reality, a “damned and hateful thing” as even St. Francis himself recognized. Yet because of the love of Jesus Crucified, Francis could cry out with boldness, “Welcome, Sister Death!” He knew that no one can escape death, but “Blessed are those whom death will find in Your most holy will, for the second death shall do them no harm.”

If we live in the love of Christ, death will not be a defeat but a victory. Only such confidence could allow a man to face death singing. As Francis is sometimes reported to have said in his final moments, “I have done my duty, may Christ now teach you yours.”

In hope, we cling to the truth of what has been revealed. We face death’s dark valley emboldened by those who have gone before. Their memory, especially this night, Francis’ memory, shapes us. Everything that he did and taught. Every last word.

And that’s the thing about last words. The best of them are not really about death at all. They are about life — about how we ought to live in the light of eternity.

So how shall we live? Just as our brother Francis did: in the love of Jesus Crucified.

This homily was preached at the observance of the Transitus of Saint Francis at the Franciscan Monastery of the Holy Land on Oct. 3, 2024.