Spoiler alert: There are plot points and details of Season 3 of “Ted Lasso” discussed throughout this column.

At the conclusion of the second season of the Apple TV+ series “Ted Lasso,” I wrote an essay extolling the virtue of the main character for his capacity to forgive others who had harmed him. I explained that Season 2 set the table for yet another betrayal, and suggested that Ted would probably find a way to help this betrayer find redemption. I was almost correct. In Season 3, Ted did not reconcile his betrayer. Rather, he created a culture of introspection, humility, repentance and forgiveness, through which the betrayer was not merely reconciled to Ted but achieved complete redemption (that is, redemption within the context of the morality tale of a situation comedy). Over the three seasons of both the show and his fictional English Premier League soccer team, the Richmond Greyhounds, Ted Lasso formed a community of characters who, though far from perfect, had learned to acknowledge, examine and seek redemption for their imperfect lives.

Through the first five episodes of Season 3, I was beginning to think that “Ted Lasso” had hung on a season too long. Some of the storylines were not merely predictable but overdone. The main one centered around a kind of Manichaean battle between good and evil that used a sledgehammer instead of a scalpel to push the theme forward. Through the stage settings, the antagonists’ wardrobes and the overdone script demonstrating the good and bad sides, the show was becoming somewhat tedious. Where subtlety was demanded, exaggeration was provided. And rather than building tension between the rival moral opponents, it created a cartoonish rivalry. Yes, yes, we get it, I was thinking. Let’s move on to see how (or if) it is resolved. But things started to turn about Episode 6. Despondent over the Greyhounds’ humiliating defeat in Amsterdam, Ted comes up with a new team strategy that he calls “Total Football,” which revived the season’s fortunes of both the soccer team and the TV show.

The cast of characters

While Ted himself remained the main character of the show, another emerges as what one might call the “moral chorus.” Sam Obisanya is a young Nigerian player on the team who provides a steady, quiet, unassuming virtuous center around which moral chaos tends to swirl. In Season 1, Sam refused a move to a Moroccan team funded by a vain and pompous billionaire, Edwin Akufo. In spurning Akufo’s offer, Sam turned down a much larger salary to instead stay at Richmond, which had given him his big break and to which he felt a sense of loyalty. Later, Sam took well-publicized moral stands on some large policy issues in the United Kingdom and his native Nigeria, which had financial costs for both him and the team. And, finally, he suffered the indignation of being omitted from the Nigerian national team — a position he had earned by his play with Richmond — after Akufo bribed the Nigerian federation to exclude Sam. Despite all these setbacks, Sam never contemplates revenge and does not wallow in self-pity. Instead, he is a serene and irenic witness to the way of forgiveness, and the most consistently sympathetic character in the show.

The narrative heart of Season 3, however, is the resolution of several personal storylines from other less composed personalities, both on and off the pitch. And all these resolutions are the result of the culture that Ted Lasso creates by his own moral strength and wisdom. Rather than going around solving all the problems and conflicts — both inter- and intrapersonal — Ted creates a moral community in which various characters find their own ways to redemption and, in many cases, help others do the same. Each of these resolutions is built around the common themes of repentance and reconciliation, through characters coming to terms with injuries and injustices that had been done to them. In other words, the strongest moral themes in “Ted Lasso” are not centered around the redemption of characters who had caused harm but rather upon those against whom the injury had been done. And it is all accomplished through a thick web of interdependence among the players and satellite characters.

In some cases, even the wicked backstory characters find redemption. But in others, their stories are either unresolved or they are left to mire in their wickedness. Like the real world, some seem never to be redeemed. This actually may save the show from becoming overly maudlin. Some reviewers have condemned the show for resolving conflicts and storylines in a mawkish way, providing overly sentimental and unrealistic solutions. I understand those criticisms, and usually would be in that chorus. But “Ted Lasso” overcomes its flirtation with mawkishness by providing serious, thoughtful and salutary moral lessons. These are not the simplistic solutions of the typical situation comedy but rather the purgatorial redemption that comes only through sincere examinations of conscience and authentic repentance. Three lines of dialogue illustrate my point.

Forming new paths

In Episode 11, Ted is trying to help one of his star players, Jamie Tartt, deal with an anxiety attack as Richmond prepares to play a critical match at rival Manchester City, the team for which Jamie’s father is a fanatical supporter. Jamie has had a very contentious relationship with his abusive, alcoholic father, who usually cheers viciously against Jamie and Richmond. Jamie harbors deep, abiding resentment, which has stunted his growth as a person (brilliantly illustrated by a visit to his boyhood home) and is now threatening his play on the pitch. In trying to help Jamie deal with the issue, Ted says simply, “If hate is not motivating you anymore, maybe it’s time to try something else.”

Later, Ted and the rest of the coaching staff are discussing whether to bring back a former coach, Nate Shelley, who had betrayed Ted and committed a petty but deeply symbolic offense against Richmond. After Nate has a bad turn of fortune (caused by his own courageous moral stand) the rest of the team wants Ted to offer Nate a place with the Greyhounds again. Another coach, Ted’s right-hand man, Coach Beard, adamantly refuses, saying he would burn the place down if Nate were brought back. He cannot forgive Nate’s disloyalty to Ted and treachery against Richmond. In response to Beard’s violent reaction, Ted says, “I hope that either all of us or none of us are judged by the actions of our weakest moments, but rather by the strength we show when and if we are ever given a second chance.” Motivated by this, Beard goes to Nate’s house and makes a heart-rending confession of his (Beard’s) own past offenses against Ted, which were far more serious than Nate’s. Ted had forgiven Beard, and that forgiveness had saved Beard’s life, he told Nate. The least he could do was to forgive Nate. Is the scene overdone? Maybe. But it can be forgiven for the forceful and authentic message of Beard’s redemption and Nate’s reconciliation. Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.

Communion

Finally, in the last episode, former star player and current assistant coach Roy Kent expresses frustration that he has tried to change his flawed personality to become a different person. He has made sincere and diligent efforts to become more open, kind and personable to the people around him. And the viewer can see that he has. But Roy is not satisfied. Indeed, he is deeply chagrined and feels like giving up. After being offered a couple of pieces of inadequate counsel by other team personnel, Leslie Higgins, a bumbling team executive says, “The best we can do is to keep asking for help and accepting it when we can.”

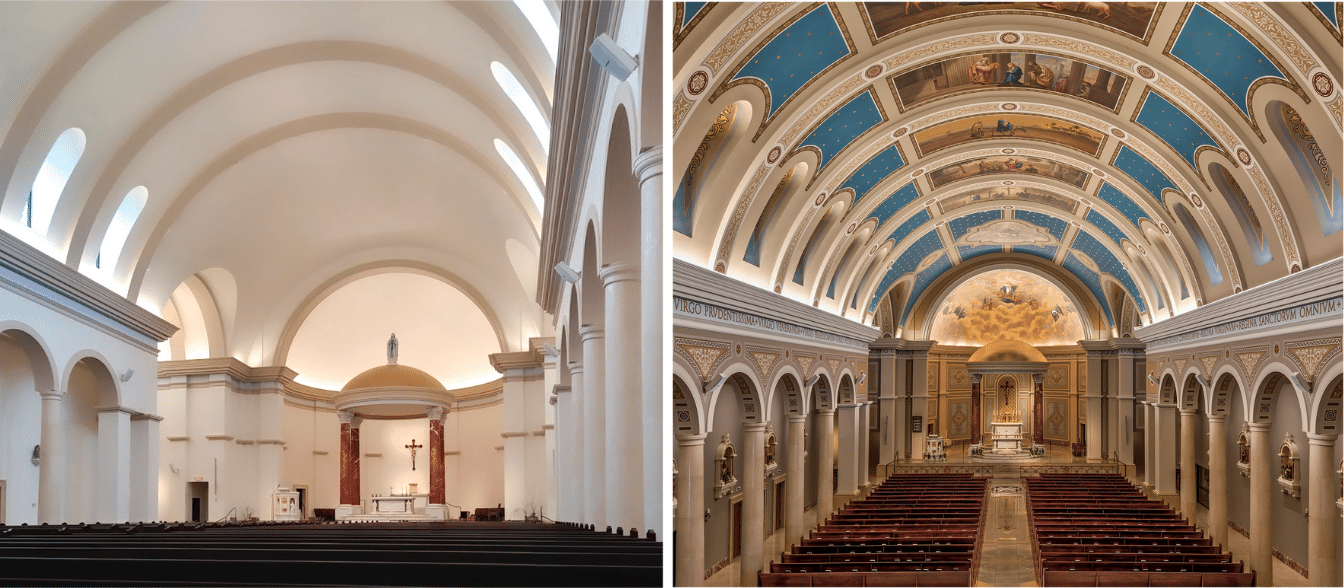

This line summarizes perhaps the most important moral theme of “Ted Lasso.” The show is built around the fundamental Catholic principle of the solidarity of the human person, created in and for community. It recognizes our moral frailty, including the mutual ways that we sometimes injure one another and, in turn, harm ourselves and the community. But “Ted Lasso” reflects the possibility of redemption through examination of conscience and proactive efforts of reconciliation with those who have hurt us. The show does not let victims wallow in their maltreatment, but gently guides them to seek reconciliation with their offenders. Does it verge on sentimentality? Perhaps. But this, too, can be forgiven. Because, after a long farewell, the Ted Lasso way is the way of the Gospel.