Dublin’s Musick Hall roared with praise for the premiere of Handel’s “Messiah” on April 13, 1742. The following year, the piece premiered in London, when according to musical tradition, King George II was so moved by the piece’s famous “Hallelujah” chorus that he leaped from his seat, standing for the duration of the movement. The rest of the attendees followed suit, beginning the tradition of standing during “Hallelujah” that has lasted to the present. And the popularity of this chorus — and indeed the entire “Messiah” — reached new heights only after Handel’s death.

From Oscar Mayer commercials, to “Dumb and Dumber,” to a flash mob in a Florida airport, Handel’s “Hallelujah” chorus has traveled far outside the bounds of the concert hall. But Handel could not have foreseen what would become one of the world’s most ubiquitous pieces of music. So how did this beloved chorus come about?

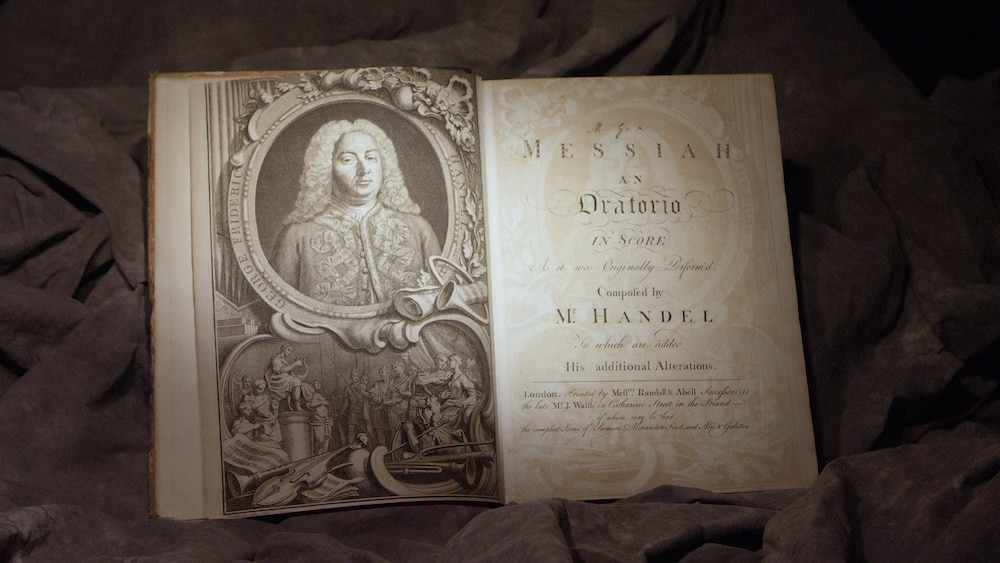

George Frideric Handel was born on Feb. 23, 1685 — the same year as Johann Sebastian Bach and Domenico Scarlatti — to George Händel and Dorothea Taust in the flourishing town of Halle, Germany. Little is known for certain about Handel’s early life, but much lore surrounding his upbringing stems from the work of his first biographer, John Mainwaring.

According to Mainwaring’s accounts, Handel’s musical development was a point of contention in his family. His father, Händel, is said to have been a rigid pragmatist. While music and other arts flourished in Halle, Händel’s position as barber-surgeon meant that he was not in a high social strata, so he and his family were socially barred from enjoying such luxuries. Handel’s father was vehemently opposed to his musical education, and according to Mainwaring, “took every measure to oppose” his son’s musical development when he showed interest in — and propensity for — music. It is believed that Händel prevented any instrument from entering his family’s house, and even forbade Handel’s to visit any houses that may have had musical instruments.

Mainwaring writes that Handel secretly acquired a clavichord — a quiet keyboard instrument popular for practicing until the Classical period — which he brought to the attic of his family home. It was here, in the quiet hours of the night, while his family slept, that Handel secretly practiced his music.

Though the credibility of this story is contested among scholars, it highlights just how deeply music can move us. Somewhere between the age of seven and nine, Handel joined his father in a trip to Weissenfels, Germany. He began playing the court organ in the palace chapel, impressing all who heard. He even caught the attention of Duke Johann Adolf I, who encouraged Händel to foster Handel’s music education.

Händel, obliged to take the Duke’s advice, allowed his son to study music. Handel studied under Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow, who abided by the methods of the “old school” — taking the form of fugues, canons and counterpoint — while simultaneously embracing newer styles developing throughout Europe at the time. This international approach would influence Handel’s own cosmopolitan approach to music-making throughout his life.

Handel quickly took on an exciting career in the European music scene, traveling from Germany to Italy, where he successfully composed in his favorite genre, opera, for four years. It was not until he settled in England, in 1712, that he moved toward writing oratorios like “Athalia,” “Esther” and “Messiah.”

Handel introduced his first Italian opera in London, Rinaldo, in 1711. The work was met with great success, and he would go on to compose another 40. But, by the 1730s, the popularity of the Italian opera waned, and Handel began to rely more heavily on private donations to subsidize his compositions.

While Handel still loved Italian opera, he began composing English-language oratorios as less expensive alternatives. Oratorios are similar to operas in scale, but typically meditate on sacred themes, and have simpler set designs.

His first English-language oratorio, Esther, was composed for a patron in 1718. Fourteen years later, Handel premiered a revised Esther at the King’s Theatre, Haymarket. He would later consistently find greater success in English oratorio than Italian opera, and abandoned opera entirely in 1741.

Later that year, after giving up on his beloved operas, Handel received a libretto — the text of a long vocal work — from his patron and friend, Charles Jennens. This libretto, compiled from the King James Bible and Coverdale Psalter, meditates on Christ as Messiah. Jennens recognized that the text he sent Handel was large in scope and weighty in subject matter, but trusted that Handel would be the composer to rise to such a challenge. In a letter to his friend, Jennens wrote: “Handel says he will do nothing next Winter, but I hope I shall perswade him to set another Scripture Collection I have made for him, & perform it for his own Benefit in Passion Week. I hope he will lay out his whole Genius & Skill upon it, that the Composition may excel all his former Compositions, as the subject excels every other Subject. The Subject is Messiah.” This libretto would inspire Handel to write one of the most well-known pieces of Baroque music, and indeed, of all European classical music: “Messiah.”

‘Messiah’

“Messiah” consists of three parts. The first part explores the texts of Isaiah leading up to the angel’s annunciation to the shepherds. Part II focuses on Christ’s passion, death, resurrection, and ascension, ending with the “Hallelujah” chorus. And Part III, the final part, portrays the resurrection of the dead, as well as Christ’s eternal glory in heaven.

Handel composed “Messiah” in under four weeks — and incredible feat for even the most prolific of composers. He is known to have eaten and slept very little during this period, rarely leaving his study. Though he was brought food, it often went untouched as he wrote with the fervor of divine inspiration. According to legend, while writing the “Hallelujah” chorus, Handel’s servant found a tear-laden Handel, saying “I did think I did see all Heaven before me, and the great God Himself seated on His throne, with His company of Angels.” The chorus has touched audiences for centuries, becoming one of the most popular pieces of choral music from the English oratorio tradition.

So, what makes the “Hallelujah” chorus so great?

The “Hallelujah” chorus is a triumphant account of Christ’s victory over death. Its text is simple, but carries with it the weight of salvation:

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth.

The kingdom of this world is become

the kingdom of our Lord, and of His Christ;

And He shall reign for ever and ever,

King of kings, and Lord of lords.

“Hallelujah” begins a bit unassumingly, with a confident — albeit light — orchestral introduction. It seems happy, but perhaps not momentous. Then, the choir introduces the famous theme: “Hallelujah! Hallelujah! Hallelujah, hallelujah, hallelujah!” It is in this theme that Handel introduces a number of musical techniques that have gripped his audience for centuries.

One of these effective, albeit simple, techniques is his shortening and lengthening of syllables. In the first two iterations of the word “hallelujah”, the first syllable is lengthened (“HAA-le-lu-jah”). In the next two, the third syllable is emphasized (“ha-le-LU-jah”). In the last iteration of the phrase, he emphasizes the second syllable (“ha-LE-lu-jah”). This changing rhythm propels the text in a burst of excitement, creating a palpable joy.

Handel’s genius with this chorus lies in his ability to transform simple musical ideas into awe-inspiring explosions of splendor. Like the main theme, the “King of kings” section uses repetition — this time, the repetition of a single note — to convey the drama of the text. With each recitation of the phrase “King of kings,” and “Lord of lords,” the music gets incrementally higher, building tension along the way. Eventually, the tension is released, with the choir and orchestra bursting together harmoniously, as composer-conductor Rob Kapilow says, “We have reached that place in heaven where all themes combine.”

The piece ends with a triumphant iteration of the word “hallelujah.” In this last iteration, Handel slows the word down, emphasizing (for the only time in the piece) its last syllable. In this grand moment, the choir and orchestra come together in one joyous “Ha-le-lu-JAH!” — a moving finale to the second part of “Messiah,” reminding the listener of the promises brought the Jesus’ passion, death and resurrection.

Handel’s “Messiah” has become a staple in Christmas listening over the past century, but I encourage you to give it a listen this Easter season. Let Handel and Jennens carry you into the cosmic vision of redemption brought by the Resurrection, and know that Christ, who came into the world as a baby and redeemed all of creation through his sacrifice, and shall truly reign “forever and ever!”

Victoria Costa is a graduate student at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland.