The first six months of 2002 marked a watershed in how sexual abuse of children and the Catholic Church were seen in the United States, as well as an inflection point for how the Church responded to allegations of abuse against priests.

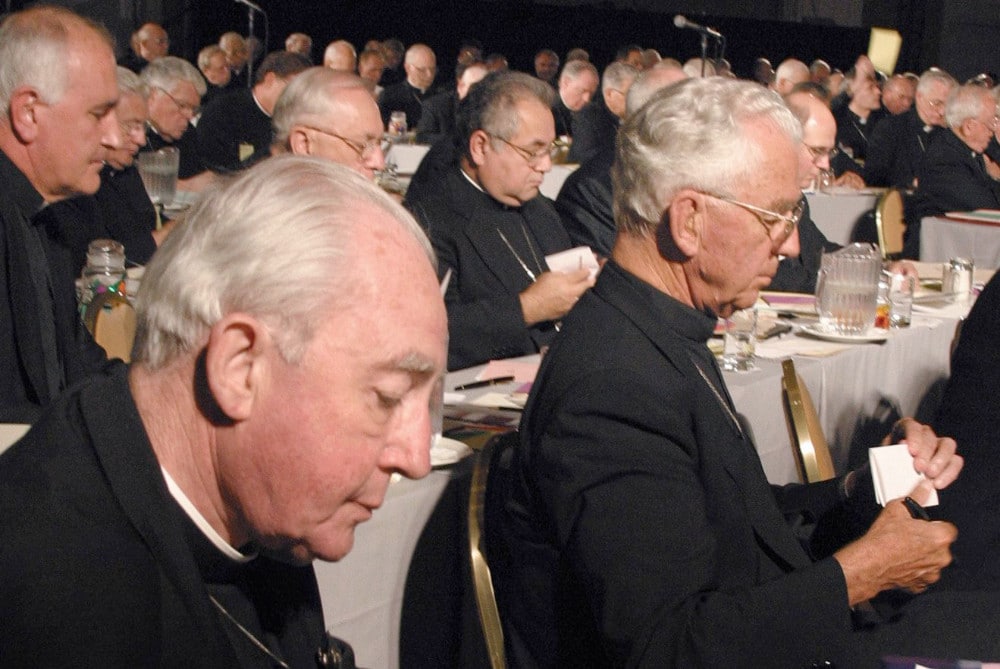

With the passage of the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in June of that year, the bishops established national norms to hold dioceses accountable for protecting children and ministering to people who had been harmed.

The charter, which has been updated three times since 2002 and will be reviewed for a fourth update next year, starts with an apology to victims. Its 17 articles discuss how parishes should promote the healing of and reconciliation with survivors of clerical sexual abuse, respond effectively to allegations, ensure accountability and try to create a safe environment “to protect the faithful in the future.”

“Just the fact that we’re talking about this — this wasn’t everyday conversation then,” said Deacon Bernie Nojadera, executive director of the USCCB’s Secretariat for Child and Youth Protection since 2011. Before that, he served as director of the Office for the Protection of Children and Vulnerable Adults with the Diocese of San Jose, California. “We’re bringing it to the light. It used to be, at all costs, avoid scandal and such. It’s now about the survivors and the victims. It’s a major paradigm shift. …

“When the bishops had met in Dallas 20 years ago in June, to be able to have this document that we have now, and then eventually the accompanying essential norms, right out of the gate it was a wonderful document to get the central Church to center in on the mission. We got this road map to gather resources, establish offices, require diocese to establish policies and procedures.”

Read part 2 in this series here.

Victim-survivors of sexual abuse by priests, child protection professionals like Deacon Nojadera and bishops say the charter undoubtedly made the Catholic Church in the United States safer for children and other vulnerable people, and it offered a path to begin to address the harm suffered by those already hurt. This boiling over of revelations of past abuse in January 2002 prompted the bishops to take action, and that action came in the form of the Dallas Charter.

Early public cases

On Jan. 6, 2002, Epiphany Sunday, the Boston Globe published the first installment of its Spotlight series on sexual abuse by priests in the Church. The story was keyed to the trial of John Geoghan, a former priest, for one instance of abuse. The newspaper didn’t focus just on that one incident, though; it discussed the 130 civil lawsuits the Archdiocese of Boston had faced based on Geoghan’s abuse of children that stretched back decades, and how, for years, Boston’s bishops knew he had abused children and kept reassigning him anyway.

The two-part investigative series, along with more than a half-dozen follow-up stories, serves as the basis for the 2015 film “Spotlight,” which won Best Picture at the 2016 Academy Awards.

From the moment the first story was published, the scandal rarely left the front pages, as dioceses around the country received hundreds of new allegations of sexual abuse by priests, announced investigations and held listening sessions. While Boston was the epicenter, the scandal widened with reports of abuse from all over the country.

The idea that a priest — a beloved pastor, even — could do something so wrong wasn’t new. Gilbert Gauthe, who had been a priest of the Diocese of Lafayette, Louisiana, was removed from ministry in 1983 and pled guilty to abusing 37 children in 1985 in a case that also made national headlines. In the early 1990s, James Porter pleaded guilty to abusing 28 children in the Diocese of Fall River, Massachusetts, while he was a priest there in the 1960s. Less than a year earlier, the diocese had settled 68 civil suits involving Porter, who died in 2005 after many years in prison.

Eventually, those earlier scandals faded.

“I recall the Jan. 6 headline from the Boston Globe and was shocked to have read that,” said Deacon Nojadera, who was working in the Diocese of San Jose at the time. “I was thinking, well, it’ll probably be a couple of news cycles. Two years later, it was still headline news. As a result of that initial headline from the Boston Globe, we started getting these reports of sexual abuse of minors involving clergy starting to pop up. The following year, in 2003, the state of California opened up its statute of limitation for this crime. For that year, the nonstop phone calls and emails of folks that wanted to report their allegations of abuse, a good number of them historical in nature … there were just so many people.”

Bishop David Kagan of Bismarck, North Dakota, also remembers being shocked at the news from Boston. At the time, Bishop Kagan was vicar general and moderator of the curia in the Diocese of Rockford, Illinois, and he worked with the diocese’s existing review board when they received allegations.

“I found it to be a bit of an aberration that a person like this priest, who was known as an abuser, would be shuffled around,” Bishop Kagan said. “In my own experience as a parish priest and a diocesan official, that was totally foreign to my way of thinking. … I have somewhat of a jaundiced view of the secular media, because they have their own agenda to pursue, but there was a kernel of truth there.”

In time, Bishop Kagan said, he came to understand that it wasn’t an aberration.

“I was thinking, well, it’ll probably be a couple of news cycles. Two years later, it was still headline news.” — Deacon Bernie Nojadera |

‘A real cascade of revelations’

Teresa Pitt Green watched the news that winter with mixed emotions. In the early 1990s, she had reported to being sexually abused by a priest when she was a child, and none of what she saw seemed new.

“I had two impressions,” Pitt Green said. “One was that I was glad, really glad, that people were coming forward and hoping that they would come out of the shadows and into the light and find comfort for what they had suffered. But I had been dealing with my survivor experience for a very long time. I was a bit jaded about the Catholic Church.”

She first came forward, she said, after already receiving years of therapy, when she was facing a brain surgery and didn’t want to die without reporting what happened to her, because she didn’t want her abuser to harm anyone else.

When she reported the abuse to the diocese, Pitt Green said, “they did their best. But they did a bad job dealing with me. They did try to listen, but it was a time when the Church didn’t know how to deal with survivors.”

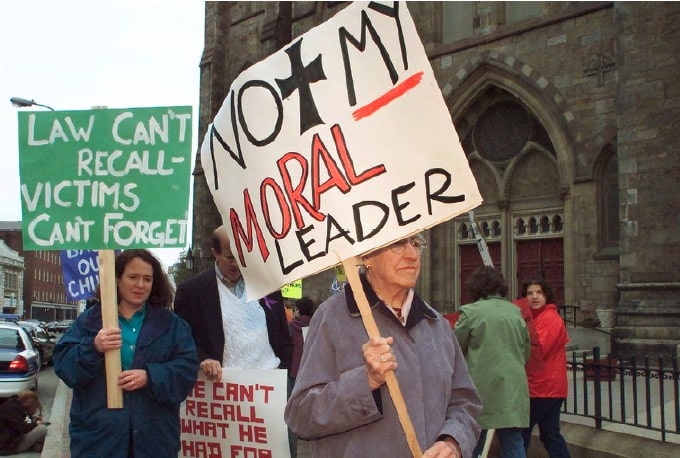

This time, though, was different. The allegations didn’t stop, and neither did the news stories or the rising anger of many Catholics — not just at offending priests, but at bishops who were seen as enabling them.

“It was a cascade, a real cascade of revelations,” said Father Thomas Berg, director of seminary admissions and a professor of moral theology at St. Joseph Seminary in Yonkers, New York. “I’m thinking of that closing scene in [the film] ‘Spotlight,’ when all the phones start ringing. … The revelations of actual abuse always make your stomach churn, and they’re awful, but in its own way, there was the awfulness of this mysterious blindness and ineptness to act on the part of the bishops that became part of the scandal.”

Berg recalled being a young man discerning his vocation to the priesthood in the 1980s and being appalled by the sexual promiscuity going on in some of the religious communities he visited. The willingness to tolerate violations of celibacy, he believes, played into the bishops’ seeming inability to deal adequately with priests who sexually abused children and teenagers.

“The bishops either turned a blind eye to it, or fell into this hapless sense of, ‘There’s nothing we can do about it. Boys will be boys,'” Berg said.

One bishop, Anthony O’Connell of the Diocese of Palm Beach, Florida, stepped down in March 2002 after news came out that the Diocese of Jefferson City, Missouri, had paid a $125,000 settlement in 1996 after a teenage seminarian had accused him of misconduct. The misconduct and the settlement took place before O’Connell became a bishop, leading then-Bishop Wilton Gregory, who was serving as president of the USCCB to say, “[There] is a serious obligation on the part of anyone, in conscience, to make such matters known. You don’t need a conference of bishops to tell you that. It’s common sense.” Now-Cardinal Gregory is archbishop of Washington, D.C.

“I had two impressions. One was that I was glad, really glad, that people were coming forward and hoping that they would come out of the shadows and into the light and find comfort for what they had suffered. But I had been dealing with my survivor experience for a very long time. I was a bit jaded about the Catholic Church.” “I had two impressions. One was that I was glad, really glad, that people were coming forward and hoping that they would come out of the shadows and into the light and find comfort for what they had suffered. But I had been dealing with my survivor experience for a very long time. I was a bit jaded about the Catholic Church.”

— Teresa Pitt Green |

First steps

Dioceses around the country held listening sessions and set new policies in place, although some of them fell short of requiring that priests with even one credible allegation of abuse against them be completely removed from ministry.

Cardinal Bernard Law, archbishop of Boston, did announce support for zero-tolerance policy shortly after the Boston Globe articles ran, and he removed at least eight priests from ministry because of prior allegations by the following month. Pope St. John Paul II called members of the leadership of the U.S. Catholic Church to the Vatican to discuss the situation at the end of April 2002.

Bishops also pointed to actions they had taken, including the 1992 resolution they adopted listing five principles for handing allegations of sexual abuse of minors by priests. The resolution recommended that dioceses:

Respond promptly to all allegations of abuse where there is reasonable belief that abuse has occurred.

If such an allegation is supported by sufficient evidence, relieve the alleged offender promptly of his ministerial duties and refer him for appropriate medical evaluation and intervention.

Comply with the obligations of civil law as regards reporting of the incident and cooperating with the investigation.

Reach out to the victims and their families and communicate sincere commitment to their spiritual and emotional well-being.

Within the confines of respect for privacy of the individuals involved, deal as openly as possible with the members of the community.

In 1993, the bishops’ conference created its ad hoc committee on sexual abuse, which would become a standing committee after the charter passed. U.S. bishops also petitioned Pope St. John Paul II for U.S. exceptions to canon law to make it easier to laicize priests who had abused children.

Also in 1993, Archbishop Robert Sanchez of Santa Fe, New Mexico, stepped down following accusations of past sexual impropriety with two teenage girls, and in the Archdiocese of Boston, John Geoghan was removed from ministry. He was laicized four years later.

Late in 1994, the ad hoc committee gave the bishops the first of three volumes of “Restoring Trust,” which included detailed evaluations of diocesan policies and suggestions for making them more effective. Updated volumes were issued in the few years after.

Deacon Nojadera said it’s important to understand that many dioceses were making an effort to respond more effectively to clerical sexual abuse of minors, but the effort was inconsistent, and even dioceses that were doing many of the things in the charter weren’t doing all of them.

Approving the charter

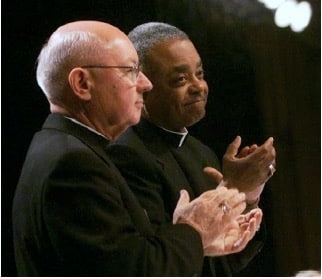

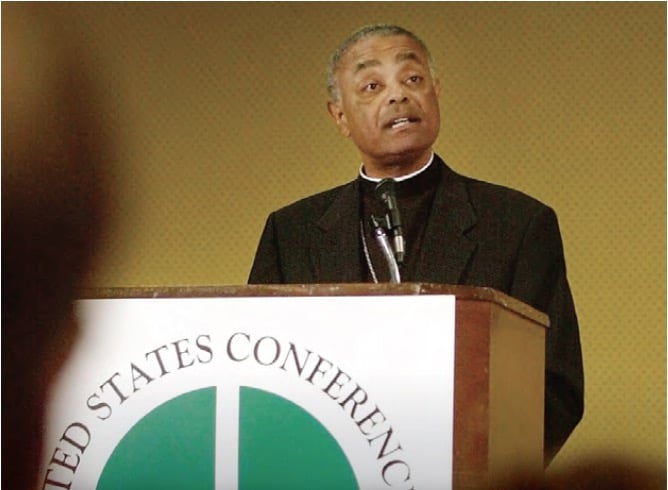

As the bishops prepared for their June meeting in Dallas, it was clear that they would take some action. A draft of the charter was made public on June 4, and Archbishop Harry J. Flynn of St. Paul and Minneapolis, the chairman of what was then the USCCB’s Ad Hoc Committee on Sexual Abuse, told media that bishops would debate a new national policy with an exception allowing for the return to ministry of priests with only one substantiated incident in the past.

Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People on June 14, 2002. CNS photo/Bob Roller

According to media coverage of the bishops’ meeting in Dallas, held June 13-15, 2002, then-Bishop Gregory said the sexual abuse crisis was “perhaps the gravest crisis we have faced.”

“We did not go far enough to ensure that every child and minor was safe from sexual abuse. Rightfully, the faithful are questioning why we failed to take the necessary steps,” Bishop Gregory said.

Cardinal Law issued a “profound apology” to his brother bishops behind closed doors; he would eventually resign as archbishop of Boston in December 2002. By the time the bishops discussed the charter in open session, they had agreed that all clerics with even one substantiated allegation must be permanently removed from ministry.

The prelates heard from lay Catholics and survivors of clerical sexual abuse, as well as from R. Scott Appleby, a professor at the University of Notre Dame, who said, in part: “The root of the problem is the lack of accountability on the part of the bishops, which allowed a severe moral failure on the part of some priests and bishops to put the legacy, reputation and good work of the Church in peril. The lack of accountability, in turn, was fostered by a closed clerical culture that infects the priesthood, isolating some priests and bishops from the faithful and from one another.”

While it was unfair to blame all bishops, or all priests, the bishops had to act to respond to a crisis that was moral, pastoral and institutional, and he suggested they do so by elevating lay leadership, Appleby said in remarks that were published in full by the New York Times on June 14, 2002. Appleby, now the dean of the Keough School for Global Affairs at Notre Dame, did not respond to a request for comment for this article.

In the end, the bishops voted 239-13 to approve the charter, and dioceses began to implement its requirements by establishing victim assistance ministries, starting safe environment programs and removing priests who had abused minors from ministry, if they had not already done so. The charter also required background checks for clergy and others who work with children, and it called for annual audits to make sure dioceses were following the charter.

But the process was not yet over, as the Holy See wanted to review the charter, and expressed concern about due process for accused clerics. In October 2002, a U.S.-Vatican commission met in Rome. It included then-Bishop Gregory, the late Cardinal Francis George of Chicago, the late Bishop Thomas Doran of Rockford, Illinois, then-Archbishop and later Cardinal William Levada of San Francisco and then-Bishop William Lori of Bridgeport, Connecticut, who is now archbishop of Baltimore.

Eventually, it was agreed that priests who were accused would be entitled to canonical trials, something that had been a problem because of the canonical statute of limitations. The Vatican agreed that the statute of limitations could be waived, allowing the bishops of the United States to proceed with implementing the charter and the accompanying “essential norms” — the policies and procedures relating to the charter, which were approved by the Vatican in 2003.

“We did not go far enough to ensure that every child and minor was safe from sexual abuse. Rightfully, the faithful are questioning why we failed to take the necessary steps.” — Then-Bishop Wilton Gregory |

A long way to go

Deacon Nojadera said getting the bishops to agree overwhelmingly to such big changes “must have been the work of the Holy Spirit,” though the Holy Spirit must also have worked through the media and the survivors who came forward, too.

“I have every gratitude and appreciation for the survivor-victims who did come forward,” Deacon Nojadera said. “Some of them who have shared with me what they had to go through to come forward — it’s extremely hard. And that Boston headline, that secular paper — if it wasn’t for that, victims might think they were the only victim of that sin.”

Responding to and caring for victim-survivors is the first article of the charter, which is important, Deacon Nojadera said. So is the insistence on lay involvement and leadership for review boards, and the necessity of zero tolerance for people in ministry who have sexually abused even one child or young person.

“The fact stated here of zero tolerance of abuse, this is being seen as a core value of the Church, not just a priority, because priorities change,” he said.

Critics were quick to point out that the charter and its penalties applied only to priests and deacons, as the bishops did not believe they had the authority to discipline one another. Bishops were to engage in “fraternal correction” when it appeared that one of them was not living up to the promises of the charter.

It also only applies to the sexual abuse of minors — that is, children under 18. The abuse of adults, whether they are 18-year-old seminarians or people who have come to priests for counseling or who need assistance because of disabilities, was not addressed.

“We are moving slowly in the right direction, but we still have a long way to go,” said Sara Larson, executive director of Awake Milwaukee, a group of lay Catholics that was formed following the summer of 2018, when then-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick was removed from ministry because of allegations that he had abused both minors and adults. (There had been rumors to that effect for years.) The same summer, a Pennsylvania grand jury reported that its investigation found that more than 300 priests had abused more than 1,000 minors over 70 years.

“The biggest problem is that policies and procedures are really important, and they do make a difference, but what we really need as a Church is a much deeper change, and that’s a change of culture and a change of heart, and that’s not something that comes with a policy change,” Larson said.

Pitt Green agrees that there is a long way to go, but she is more hopeful now.

“I couldn’t be Catholic if it wasn’t for the charter,” said Pitt Green, who now lives at a retreat house operated by a Catholic religious community and offers pastoral care to people who have suffered trauma or addiction. “My life will never be what it would have been [without being abused]. I can grapple with that much better if I know there aren’t going to be as many child victims.”

The Church, she said, became a leader in its handling of child sexual abuse after the 2002 Dallas meeting, despite its earlier failures and ongoing faults.

“If you look at the prosecution of child abusers in the 1980s, it was very rare, not just in the Church,” she said. “The level of bravery for people to come forward is bigger than people stop and think. … It reflects how ambivalent society is toward child abuse victims even now. It makes me proud that in my church, this is the standard, at least in my country.”

Michelle Martin writes from Illinois.