In his homily on Psalm 148, St. Augustine speaks about the feast of Easter in a way that may sound strange to modern sensibilities. Today, Easter, like many feasts of the Church, is treated as but a single day. The feasting on chocolate, meats and cheeses gives way quickly to the resuming of the school year and to the workday world.

Not so, cautions St. Augustine. Easter is a feast that lasts 50 days, during which the alleluia song is to be close to the lips of Christians. For St. Augustine, the singing of alleluia is not just a marker that a period of fasting has concluded. Instead, the Christian is to sing alleluia as a discipline, an exercise, in which every Christian prepares for a heavenly existence. The 50 days of Easter is a contemplative mediation for the Christian on what it means to sing alleluia properly, to attune the voice of praise with the inner delight of the heart. Easter is an extended period in which we learn to become members of the Communion of Saints, an exercise of the heavenly imagination.

Even our churches seem to have given up on this Easter exercise. Sure, we preach from the pulpit that Easter extends for 50 days. We know that the commemoration of the Resurrection does not conclude until the closing evening of Pentecost. But, compared to Lent, there is little energy given to Easter. There are no evenings of prayer or reflection. Parish missions, popular during Advent and Lent, are noticeably absent from the Easter season. It is a rare parish community that appropriately celebrates the extended Vigil of Pentecost, preferring a speedy Mass that marks the arrival of summer rather the culmination of Paschal joy. Yes, there are first Communions, confirmations and ordinations to the priesthood. But few witness these rites — some even walk out of Mass when they realize that it’s time for yet another first Communion.

What if our parishes devoted the same spiritual energy to Easter that we do to Advent or Lent? How might this attention to Easter be a source of renewal of parish life, of Catholic culture in general? To answer these questions, we must learn to receive the gift of Easter anew.

Timothy P. O’Malley, Ph.D., is managing director of the McGrath Institute for Church Life.

The transfigured body

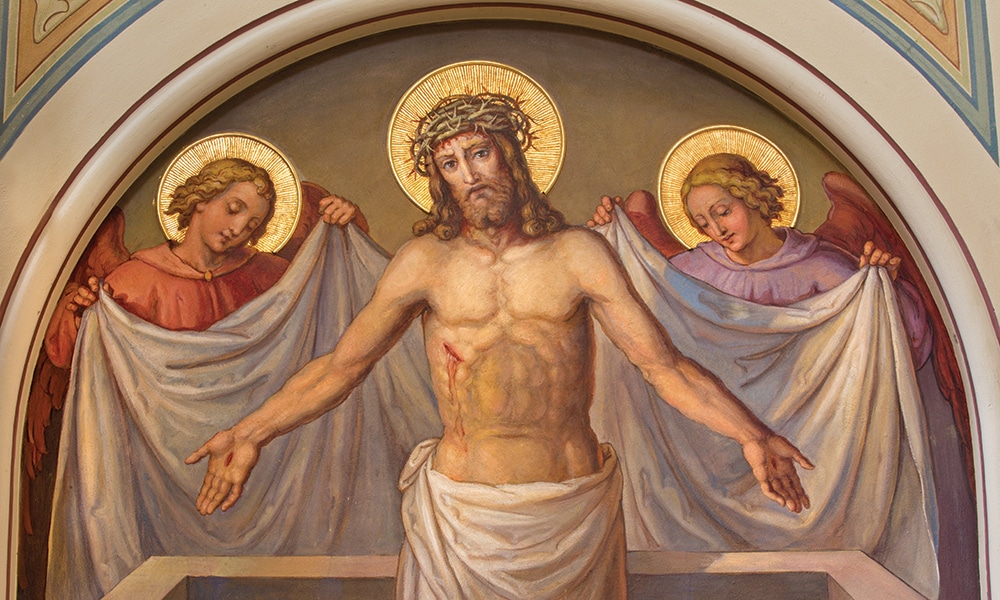

Accounts of the Resurrection in the Scriptures focus on the transfigured body of Our Lord Jesus Christ. This makes sense. Over the course of Holy Week, we attend to the embodied quality of Christ’s suffering on the cross. He sweats blood as he contemplates his own death within the Garden. The crowds spit at him. Whips flay his flesh while his head oozes blood because of the crown of thorns that prick his skin. As he dies, he gives up a final breath, suffocated by the cruel torture of crucifixion.

Our contemplation of such embodied suffering is not a form of masochism whereby we delight in the torture of Christ. Rather, it is an extension of a mystery that we delighted in at Christmas: “the Word became flesh” (Jn 1:14). In becoming flesh, the Word has shared in the fullness of what it means to be human. Yes, this sharing in human existence means the delight of friendships, of having a mother, of feasting with the disciples. It also means fragility, possessing a body that oozes and bleeds when pricked. As we all know, our embodiment is both a gift and a curse, for the very body that enables us to cuddle with our newborn child will eventually cease to function — our breath will fade away. We don’t live forever. We are oriented toward death.

Of course, Our Lord Jesus Christ does not die a death like any other death. He doesn’t die in the presence of his friends and family. He is beaten; life is violently taken away from him. His body becomes an object of derision for the state, the religious authority, even the passersby who skewer him with insults and spittle alike. He takes upon his body the sins of the world, a darkness that is in radical contrast to the luminous love he exhibits to the thieves, to his mother and the beloved disciple. And it seems, at least initially to those gathered on Calvary, that the darkness wins.

But, as we felicitously know, death doesn’t win. The Father raises Christ from the dead on the third day, after Jesus enters into the depths of hell and brings the patriarchs into heaven. The remembrance of Holy Saturday is in radical contrast to what the disciples experienced between Good Friday and Easter morn. The women traipse to the tomb, expecting to encounter the dead body of their beloved rabbi. Instead, they find nothing. Peter and John run to the tomb, discovering the mystery of burial cloths tossed to the side. Is there a reason to hope? Or is this just a terrible prank, the final degradation of their once-beloved Jesus?

The absence of the body is disturbing. And that’s why we need to learn to be more forgiving of Thomas. Unlike the others gathered in the upper room in the Gospel of John, he doesn’t see the risen Lord. He encounters only absence. In placing his fingers in the side of Jesus, Thomas is not just “proving” that the Lord is raised. He is not a precursor to a scientific empiricism in which “seeing is believing.” Rather, Thomas presents to us an image of what the Resurrection means — the wounds of love still mark his body. It is our flesh that is now glorified, transfigured through a love that could not be conquered through death. Love, total and absolute love, has transformed what it means for us to be human — to be embodied creatures.

This transformation requires a change in how we see. The disciples on the road to Emmaus in the Gospel of Luke know the difficulty of learning to see in this way. They walk, heads lowered, away from Jerusalem. They’ve given up on the project of Jesus, for surely he could not be the Messiah. He is not the one who has come to redeem Israel, for he died as one cursed upon a tree. They expect one history, one story, but have received another.

Raised from the dead, the glorified body of Jesus Christ tells this other story. He interrupts them in their pity. He shows them that the resurrected body, proof of a love that descends even unto death, is the meaning of history. At last, they understand. They invite him into supper. And at this moment, as he takes bread, blesses it, breaks it and gives it, they see. They see all along whom the stranger was. Jesus Christ is the one who is gloriously present, entering into the suffering of the human condition and transfiguring it. What seemed like absence, death and destruction is actually the source of a divine presence that has forever transformed what it means to be human. We are not those waiting for the carnival of death, rejecting all meaning in life. We are those who gather around our risen Lord, aware that darkness has lost. Light shines, even into the darkest crevices of human history.

The feast of Easter is our invitation to see in this way. The gift of Christianity is that the darkness is not erased. We’re not a Pollyannaish faith that sees death as something that must be endured but quickly passed over. Christians make bad stoics. But, we make excellent disciples of the risen Lord.

The task of Easter is thus not to turn away from the darkness. It is not to deny it, saying, “Don’t worry, there’s a bigger plan.” Instead, it is to enter into the darkness, into the hellish places of human history, recognizing that especially there God dwells.

It is the transfigured body of Our Lord that can give us hope. Easter faith does not deny that people still die. Easter faith does not mean that all disappointment or destruction disappears. Easter faith is the recognition that disappointment, destruction and death do not have the last word. Only our risen Lord, who entered into the most hellish of all histories, does. Love wins. Indeed, that is cause to sing alleluia.

The mission of the Church’s communion

Of course, one might object: “Dear Tim, these are beautiful thoughts. But Our Lord was risen what seems like eons ago. In the meantime, I suffer from loneliness, poverty, from discrimination, from racism, from all that the world can throw at me. Where can I meet this supposedly ‘risen Lord?'”

If we believe that the Resurrection was reserved simply to one time, one place, then one would be right to raise this objection. After all, Christ was raised from the dead 2,000 years ago. In the meantime, the world has experienced war after war, genocide after genocide, misery after misery.

But Christ’s resurrection is not reducible to a historical event that happened once upon a time. Yes, Christ was raised from death, forever transforming history. But he is still risen, his wounds of love never disappearing. And it is this presence of total, absolute love that is now available through the Church.

“Wait,” you might object. “In this Church! In this Church in which prelates have too often seized power, in which clerics have abused children, in which parishioners have set up hierarchies of power that have erased those on the margins?” Can we feasibly believe that the Catholic Church, the one suffering from so much scandal at present, is also the place where the risen Lord acts?

Of course, this particular scandal is but one feature of a scandal we regularly experience in Catholicism: the scandal of the Incarnation itself. God has chosen to save humanity not through an abstract, disembodied distribution of divine grace as would be fitting of a transcendent, eternal God. Instead, God radically has entered into history. When Christ ascends into heaven, he does not leave behind the body. It is the glorified and risen body of Christ, sitting at the right hand of the Father, who is forever united to the Church. In every parish throughout the world, no matter how tepid the preaching, corrupt the clergy or apathetic the assembly, Christ metes out salvation through the embodied, material, very real Church.

This does not mean that we should be satisfied with a tepid, corrupt and apathetic parish community. In the season of Easter, we listen once more to the farewell discourse in the Gospel of John. Here, Christ offers to the Church a blueprint of what it means to belong to his resurrected Body. Christ is the vine. We are to allow ourselves to be entirely grafted to him, enjoying by means of participation the very union of love that he shares with the Father. This abiding is not reducible to an internal decision on our part. It involves keeping those concrete commandments that Christ has given: “This is my commandment: love one another as I love you. No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (Jn 15:12-13).

During the season of Easter, the Church is to become once more who she is: the communion of love with Christ, the communion of love with the Father, longing to sacrifice herself for the salvation of the world. The Church is not a community of the self-satisfied, happy to be saved while the rest of the world burns. Rather, the Church is the Bride of Christ longing to share this love with the rest of humanity. As we celebrate on the Fourth Sunday of Easter, the Church is to imitate the Good Shepherd, willing to lay down his life for his sheep.

If this capacity to become the communion of love shared between the Father and the Son was dependent on the Church alone, it would be an impossible task. The Church has proven this in era after era. In the 11th and 12th centuries, many bishops and priests in the Church had been reduced to feudal lords, seeking in ordination not the pursuit of sanctity but the acquisition of power. That the Church has survived these scandals is dependent not on her own remarkable ingenuity, her own capacities to reform, but the Spirit of Christ that softens her heart, fructifying her for the flourishing of the world.

For this reason, the season of Easter ends with the feast of Pentecost. We do not experience the presence of Christ in precisely the same way that the disciples did. But, we do have the gift of the Holy Spirit, the very love of God that is working in the world through the body of the Church, through the Communion of Saints and through our very bodies.

The descent of the Spirit on the apostles and the other disciples has extended the mission of the Church beyond those gathered in the upper room to the very ends of the world. Catholicism, as it turns out, is not a denomination. Instead, in Catholicism we find the hope made flesh with which every human being will be knit into the eternal love of the Father and the Son, a participation made possible through the descent of the Spirit.

In the Acts of the Apostles, read throughout Easter, we hear about this missionary dimension of the Church. It is not enough for individual Christians to experience salvation. The task of the Church is to run to the margins, sharing with every human being the Good News that love has conquered death. During the season of Easter, we are to learn to become a church not of individual members or parishioners. Instead, we are to practice belonging to the Communion of Saints, those who have preached the Good News that love defeats death whatever the cost.

An apocalyptic faith

And one must admit that the Good News of Easter requires the possibility of a cost for the disciples. If Christ was crucified because he manifested a divine love, a love that human sin rejected, then we should not be surprised if we experience this same rejection. When we proclaim the Resurrection and celebrate Easter, we see the first fruits of redemption. But there is still quite a harvest to bring in.

For this reason, the Church turns her attention during Easter to the Book of Revelation. Fundamentalists read this book of the Scriptures as a manual of the last days, looking for precise historical events that correspond to the strange imagery described by John in this last book of the Bible. But this is not how Catholics go about the reading of the Book of Revelation.

Instead, we read it as an apocalyptic and sacramental book, one where that which is most hidden — the heavenly love of the Lamb once slain — eventually will reveal itself in every dimension of the human city. The violence of the Book of Revelation is evident. There are wars, murders, plagues and monstrous forms that do battle with the Lamb once slain. At the same time, there are interruptions of this violence, moments in which we as readers are invited to gaze at an alternative polis, a city that has been constructed for worship of the Lamb once slain alone.

We need only think about the present city, the politics of our age, to see the radical vision offered by the Book of Revelation. Too often, human dignity is denied to those on the margins of society — including the unborn, the migrant and the elderly — because might is the only thing that matters. Such corruption enters into the Church herself (something that the Book of Revelation underlines through its condemnation of various churches in the Empire). Despite our claim that Christ is risen from the dead, that love wins, it too often seems that violence, force and power remain the currency of the kingdom. It’s more profitable to worship anything but God.

The Book of Revelation provides a terrifying hope, something that we must contemplate over the course of the Easter season. There will be a final judgment. Divine wrath will be poured out on those who refuse to live according to the politics of radical, self-giving love. Babylon will be judged. In preaching the Resurrection, in conforming ourselves to the love of Christ, we’re not just building up a nice society of the happy, friendly, good-natured folks who enjoy sharing pancake breakfasts and educating their kids in decent schools.

Every time we celebrate the Eucharist, our parish is learning how to exist within a new political order. We’re learning what it means to operate not according to might or prestige but through a sacrificial love poured out in what looks like bread and wine. We’re learning that the only way to experience communion is not through a forceful, violent rhetoric but through sacrificial love made manifest on the altar. Through worship of the Lamb once slain.

The experience of Easter means that it’s time to take this Eucharistic practice far more seriously. Mass is not about a Sunday obligation. It’s about learning to belong to the Communion of Saints, those who do not gather together because of a political platform or a shared mission statement. We belong to a heavenly city, one that is meant to transform this world. We belong to a parish and we go to Mass because we’re learning to let divine love — starting with our own hearts — infuse every dimension of the cosmos.

We’re learning to hope that what God has done in Jesus Christ is not just a once upon a time kind of thing. Instead, it is the very hope that gives meaning to our lives. It is the hope that is to give meaning to every culture in the world. For the heavenly Jerusalem will descend at the end of time, transforming this world. And we are to live in this world as if this will be the space that Christ will transform. Every tear will be wiped away and mourning will be no more. God has promised that the Resurrection, the glorious love of the Lamb once slain, will make all things new.

We need at least 50 days to learn this terrifyingly lovely, terrifyingly beautiful, terrifyingly good truth.

Christ is risen. Alleluia! He is risen indeed.