There are 576,459 words in “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy — far too few to contain all that is revealed therein. In his review of the first volume of the three-volume series, C.S. Lewis likened the tale to “lightning from a clear sky … [with] beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron … a book that will break your heart” (“On Stories: And Other Essays on Literature”). We might not consider ourselves the kind of people who need any more heartbreak, let alone the kind of people who have the time to read so many words for the sake of heartbreak. And yet, the heartbreak of which Lewis speaks is healing, restorative and perhaps even necessary, especially in times such as ours.

Would it be fair to say that, in our times, the powers of the world appear ever on the rise, hope is rather scarce, those who discern patiently and exercise responsibility are few and far between, and the meek continue to be trampled underfoot? Has not a prevailing sense of gloom fallen upon our world? Do we not yearn for a happiness we have forgotten or not yet known?

As Lewis noted in his friend J.R.R. Tolkien’s masterpiece, in “The Lord of the Rings” we are plunged into a darkening world with characters submerged in anguish. But their anguish is of those who desire more than the inevitable doom thrust upon them. They set out on a journey against all odds. And yet, when we have seen them through all their travels and travails across 576,459 words, we, like them, “return to our own life not relaxed but fortified,” as Lewis wrote.

For a Catholic such as Tolkien, we might assume that religion would serve the purpose that Lewis says this literature serves. Yet, there is no religion in “The Lord of the Rings.” There is magic and even glimpses of the demonic, but the world Tolkien creates is a world wholly contained within itself. It is a large world, an old world, even a mythological world in its own way, but everything is within that world. This is not unintentional, nor is it evidence of some kind of disclaiming of religion in general or of Tolkien’s own Catholicism in particular. To the contrary, as Tolkien himself confessed to a (priest-)friend in a letter from 1953: “‘The Lord of the Rings’ is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like ‘religion,’ to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.”

The letters of J.R.R. Tolkien

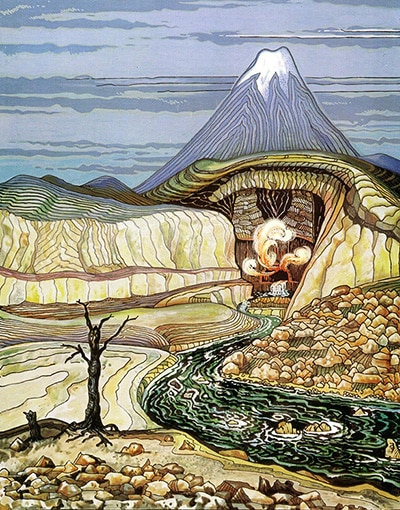

If it took 576,459 words to build that world (not counting the words in “The Hobbit” and accompanying literature), and if even that number of words cannot contain the revelation of what was absorbed therein, then the measly few thousand words in this article will certainly not fully disclose the haunting beauties of “The Lord of the Rings.” I take up instead a more limited task: to name four key elements of the narrative characteristic of a Catholic worldview, which Tolkien embeds within the tensions and choices of his characters. At times, these elements are reflected in the landscape and accompanying imagery, but to account for all of that would take us too far afield of our humble task, which is to reckon with power, hope, discernment and meekness.

| Format of ‘The Lord of the Rings’ |

|---|

While J.R.R. Tolkien wrote “The Lord of the Rings” as one continuous novel that was subdivided into six “books,” or sections, his publisher decided a trilogy was a better idea. With that said, each of the three volumes is divided into two books:

|

Disarming power

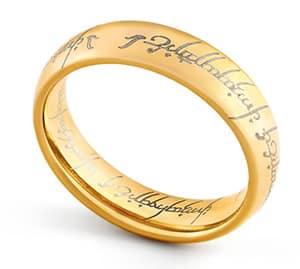

The tale of the great Ring of Power is a wholly unexpected journey. The journey goes against the expectations of worldly power. The Ring is borne by the least likely. It is carried toward its own undoing. Its power is not employed but resisted, leading thus not to domination but to fellowship.

Were the Ring leveraged according to the wisdom of the world, the quest would be doomed from the start. The great power of darkness anticipates those who would seek to elevate themselves and has armed himself against their advancements. Those who lust after power always expect others to lust after it, too, and so the only chance for truly casting down the mighty from their thrones is not to outmuscle them but to outwit them. That means not seeking to take their place, as Gandalf teaches his companions right in the middle of everything:

Were the Ring leveraged according to the wisdom of the world, the quest would be doomed from the start. The great power of darkness anticipates those who would seek to elevate themselves and has armed himself against their advancements. Those who lust after power always expect others to lust after it, too, and so the only chance for truly casting down the mighty from their thrones is not to outmuscle them but to outwit them. That means not seeking to take their place, as Gandalf teaches his companions right in the middle of everything:

“The Enemy, of course, has long known that the Ring is abroad, and that it is borne by a hobbit. … But he does not yet perceive our purpose clearly. He supposes that we were all going to Minas Tirith; for that is what he would himself have done in our place. And according to his wisdom it would have been a heavy stroke against his power. Indeed he is in great fear, not knowing what mighty one may suddenly appear, wielding his Ring, and assailing him with war, seeking to cast him down and take his place. That we should wish to cast him down and have no one in his place is not a thought that occurs to his mind. That we should try to destroy the Ring itself has not yet entered into his darkest dream” (Book III, Chapter 5: “The White Rider”).

As Mary sings in her Magnificat, the undoing of worldly power means casting down the mighty from their thrones and dispersing the arrogant in the imaginations of their minds and hearts. It does not mean meeting worldly power with more worldly power, just to replace whoever’s in charge. This journey is unexpected because it confounds the expectations of the mighty and the proud.

Elsewhere, Tolkien unfurls this strange logic in the choice of one of the most powerful figures in his created world: Galadriel, Lady of the woods of Lothlórien. She reveals that the duty of the mighty who are endowed with the power to sway events and move both mind and hearts is, in the end, to yield. Ones such as her must give their might in service of a mission they themselves do not design. She and those like her stand in the place of John the Baptist, who, though drawing throngs of people to himself in the wilderness, simply walked away when the time came to order his mission to the one he was called to serve: “He must increase; I must decrease” (Jn 3:30).

Amid a crisis like John’s, the majestic Galadriel stands before her greatest temptation: the temptation to increase her power rather than yield to the mission of one who exceeds her only in meekness:

“‘You are wise and fearless and fair, Lady Galadriel,’ said Frodo. ‘I will give you the One Ring, if you ask for it. It is too great a matter for me.’

“Galadriel laughed with a sudden clear laugh. … ‘I do not deny that my heart has greatly desired to ask what you offer. For many long years I had pondered what I might do, should the Great Ring come into my hands… And now at last it comes. You will give me the Ring freely! In place of the Dark Lord you will set up a Queen. And I shall not be dark, but beautiful and terrible as the Morning and the Night! Fair as the Sea and the Sun and the Snow upon the Mountain! Dreadful as the Storm and the Lightning! Stronger than the foundations of the earth. All shall love me and despair!’

“… Then she let her hand fall, and the light faded, and suddenly she laughed again, and lo! she was shrunken: a slender elf-woman, clad in simple white, whose gentle voice was soft and sad.

“‘I pass the test,’ she said. ‘I will diminish, and go into the West, and remain Galadriel'” (Book II, Chapter 7: “The Mirror of Galadriel”).

Galadriel intends to do good, and yet even one with the right intentions would fall prey to the corruption of unrivaled power. Were she to take the Ring, she would become a slave to the power she possesses, even as she enslaves others with unsympathetic plans for the good. The use of force is itself complicity with evil, even for noble pursuits.

As Mary sings in her Magnificat, the undoing of worldly power means casting down the mighty from their thrones and dispersing the arrogant in the imaginations of their minds and hearts.

Hope rises

Amid the encircling gloom of the powers of the world that appear all too often irresistible and inevitable, hope abides. Hope’s abiding is at times but a whisper, a small crack of light, the hint of some other way, the rumor of dawn. And yet, hope remains so long as one draws breath, and even thereafter so long as there are others to abide in hope. Hope’s resilience is proven by the gloom that threatens to snuff it out. The more the shadows persist and grow, the longer hope endures as the possibility and the promise that this too shall pass.

For Théoden, King of Rohan, the darkness was not so much outside of him as it was in his own mind. He had been imprisoned by the counsel of the wicked. At some point, he went along willingly to some degree, but later his own agency had been reduced so severely that he could not even control his own thoughts. In due time, though, another counselor came to his aid, one unlooked for whose arrival always surprises. And so, in discourse with Gandalf, a new way is opened to the weary king:

“‘Now Théoden son of Thengel, will you hearken to me?’ said Gandalf. ‘Do you ask for help?’ He lifted his staff and pointed to a high window. There the darkness seemed to clear. And through the opening could be seen, high and far, a patch of shining sky. ‘Not all is dark. Take courage, Lord of the Mark; for better help you will not find. No counsel have I to give to those that despair. Yet counsel I could give, and words I could speak to you. Will you hear them? They are not for all ears. I bid you come out before your doors and look abroad. Too long have you sat in shadows and trusted to twisted tales and crooked promptings'” (Book III, Chapter 6: “The King of the Golden Hall”).

Théoden was a man possessed. The exorcism which Gandalf initiates is not one done only for Théoden but indeed must be done with him. Théoden’s sickness is that he has given control over himself to the beguilements of another; when his healer appears, this healer will not simply exchange one enchanter for another. No, Gandalf shows Théoden that the king is not the passive recipient of hope. Théoden must choose to see and accept another way. And he does.

Even if he is firm with Théoden, Gandalf will not seek to dominate the king. That, again, would be a trick of the Enemy. Hope is the power to wait with and act for those in captivity, to help restore them to their rightful dignity, and to empower them to break free of the chains that hold them. Hope builds upon those who tend to the wounds of others and who cling to one another in friendship, refusing to make enemies out of friends. Friendship itself is the great testament to hope, as the elf Haldir speaks to:

“Indeed in nothing is the power of the Dark Lord more clearly shown than in the estrangement that divides those who still oppose him. … The world is indeed full of peril, and in it there are many dark places; but still there is much that is fair, and though in all lands love is now mingled with grief, it grows perhaps the greater.” (Book II, Chapter 6: “Lothlórien”).

Hope’s abiding is at times but a whisper, a small crack of light, the hint of some other way, the rumor of dawn. And yet, hope remains so long as one draws breath, and even thereafter so long as there are others to abide in hope.

Discernment and responsibility

It is the responsibility to one another and the commitment to serve the needs of those that lack power that combine to create some of the sharpest tension in “The Lord of the Rings.” This tension is felt most acutely when characters must discern their own path. They are often pulled by competing desires, rarely though occasionally with one side clearly seen as the way of darkness. To those entrusted with a mission or a share in a mission, the need is great for patient pondering, deliberations about priorities, and repeated sacrifices. This all becomes stunningly apparent when Aragon, the rightful heir as King of Gondor, gazes upon his long-awaited destiny, which he must now delay for the sake of friendship and his more pressing duty:

“Turning back they saw across the River the far hills kindled. Day leaped into the sky. The red rim of the sun rose over the shoulders of the dark land. Before them in the West the world lay still, formless and grey; but even as they looked, the shadows of night melted, the colors of the waking earth returned: green flowed over the wide meads of Rohan; the white mists shimmered in the water-vales; and far off to the left, thirty leagues or more, blue and purple stood the White Mountains, rising into peaks of jet, topped with glimmering snows. Flushed with the rose of morning.

“‘Gondor! Gondor!’ cried Aragorn. ‘Would that I looked on you again in happier hour! Not yet does my road lie southward to your bright stream. …

“‘Now let us go!’ he said, drawing his eyes away from the South, and looking out west and north to the way that he must tread” (Book III, Chapter 2: “The Riders of Rohan”).

The path of the heart’s desire is the one from which it is most difficult to turn aside. There is nothing dark in what Aragorn sees away to the South: It is arrayed in splendor and bursting with light. And yet, for the one who discerns not just by passion or even by the allure of destiny but also deliberates with reason, the freedom to forgo for a time a beautiful path such as this becomes the hard-chosen desire. Instead of pursuing his throne, Aragorn goes in search of his small friends who have been captured by the Enemy.

It is again the chords of friendship that complicate the choices of another member of the fellowship, who now finds himself all alone and standing over what he believes to be the dead body of his closest companion. Samwise Gamgee’s task was to accompany Frodo, the Ringbearer, all the way to the end of the journey, or until death. But death, it seems, has come first for Frodo, and so Samwise must choose whether to remain with his now lifeless friend, to flee back to his own home, or to pick up the burden of the Ring himself and venture forth to complete the journey alone:

“‘What shall I do, what shall I do?’ [Samwise] said. ‘Did I come all this way with him for nothing?’ And then he remembered his own voice speaking words that at the time he did not understand himself, at the beginning of their journey: I have something to do before the end. I must see it through, sir, if you understand.

“‘But what can I do? Not leave Frodo dead, unburied on top of the mountains, and go home? Or go on? Go on?’ he repeated, and for a moment doubt and fear shook him. ‘Go on? Is that what I’ve got to do? And leave him?’ …

“‘I’ve made up my mind,’ he kept saying to himself. But he had not. Though he had done his best to think it out, what he was doing was altogether against the grain of his nature. ‘Have I got it wrong?’ he muttered. ‘What ought I have done?'” (Book IV, Chapter 10: “The Choices of Master Samwise”).

Before and after his decision, Samwise must reckon with the pull of competing loyalties. He alone can choose, and he alone must reckon with the consequences. It is his responsibility that hangs in the balance. In the conclusion of this episode, Samwise finds himself eventually pursuing both ends: seeking after Frodo and carrying the Ring, since Frodo is shown to still be alive and has been taken captive in the direction Samwise must go anyway to bring the Ring toward its destruction. But, as they say, the struggle is real. Sam had to make a choice. Such is the plight of the small and meek who weigh the choices of kinship and valor, who are burdened with the weight of fidelity, whose actions, even when errant, are not in vain, for they seek the right end in the right way and add to their own load the responsibility of wielding their own freedom and their love for others.

Such is the plight of the small and meek who weigh the choices of kinship and valor, who are burdened with the weight of fidelity, whose actions, even when errant, are not in vain, for they seek the right end in the right way and add to their own load the responsibility of wielding their own freedom and their love for others.

What goes unseen

The entire journey to destroy the Ring of Power is unexpected because the greater part belongs not to the strong but to the weak, not the wise but the foolish, not the mighty but the meek. It is a journey against all odds, but to not make the journey would be tantamount to despondency bound for utter despair. The greatest power of evil is the power to disempower those who are good, convincing them that there is nothing to do, nothing to try, nothing to hope for. But evil eyes — even the Evil Eye — cannot see the courage of the meek and humble who make the effort and carry on the work of the world’s hope despite the appearance of futility. As Elrond says at the council wherein the fellowship was forged:

“The road must be trod, but it will be very hard. And neither strength nor wisdom will carry us far upon it. The quest may be attempted by the weak with as much hope as the strong. Yet such is oft the course of deeds that move the wheels of the world: small hands do them because they must, while the eyes of the great are elsewhere” (Book II, Chapter 2: “The Council of Elrond”).

The prize for those who make the effort — who attempt great deeds and hope great hopes, in spite of or maybe even because of the sometimes overwhelming darkness that envelopes them — is not to flee into flights of fantasy or to rest on the laurels of great feats accomplished or attempted, but rather to discover within themselves a greater responsibility and love for the small and oftentimes very ordinary worlds from which they have come. This is what Lewis recognized about readers who persevere to the end of this great tale. But it is first of all what the small and meek hobbits realize themselves when, after the great journey to Mount Doom is complete. They return to their own humble Shire and are inflamed with passion for that which has been entrusted to them personally:

“This was Frodo and Sam’s own country, and they found out now that they cared about it more than any other place in the world. Many of the houses that they had known were missing. Some seemed to have been burned down. …

“‘Raise the Shire!’ said Merry. ‘Now! Wake all our people! They hate all this, you can see: all of them except perhaps one or two rascals, and a few fools that want to be important, but don’t at all understand what is really going on. But Shire-folk have been so comfortable so long they don’t know what to do. They just want a match, though, and they’ll go up in fire'” (Book VI, Chapter 8: “The Scourging of the Shire”).

The ones who made the unexpected journey became the bearers of hope, the heralds of friendship, and the beacons of light of others. They may have been meek, but the meek did not merely inherit Middle Earth: They redeemed it.

This is the anguish — the heartbreak — that leads to renewal. It is the renewal of one’s own heart. The match that lights that flame is the vision and the witness of those who have hoped great hopes and journeyed great journeys. The hobbits grew in love for the Shire and their wider world because they themselves suffered and fought for it. They awakened other hobbits to the love that lay dormant in their own hearts. They were each responsible for this place and these people. The ones who made the unexpected journey became the bearers of hope, the heralds of friendship, and the beacons of light of others. They may have been meek, but the meek did not merely inherit Middle Earth: They redeemed it.

Leonard J. DeLorenzo, Ph.D., is director of undergraduate studies in the McGrath Institute for Church Life and teaches theology at the University of Notre Dame. Find information about his books, articles and public speaking at leonardjdelorenzo.com.