Everyone passing away leaves behind material traces of their life. The existence of a Jewish man, called Jesus of Nazareth, is supported by strong historical evidence. The question therefore is raised: Are the various artifacts associated with his life truly authentic?

Apart from this question, the history of relics — authentic or fake — is an amazing, fascinating chapter of Christian history through the centuries, especially the relics of Jesus Christ, which remain the most venerated and famous.

Not everyone has the ability to travel and venerate these relics throughout Europe and the Middle East, the geographic areas where they are concentrated. Instead, Our Sunday Visitor offers you a brief presentation of 10 of these holy artifacts, such as the Shroud of Turin, the Crown of Thorns, the Holy Nails and the Holy Coat, which have survived through the present. Read on to take a journey through history and science, investigating the mysteries of many of Jesus’ relics.

1. The Holy Cross

Once, Martin Luther said that “one could build a whole house using all the parts of the True Cross scattered around the world,” mocking the Catholic tradition of venerating relics and pilgrimages to places where they were located.

This is not true. According to meticulous research carried out in the 19th century, all the known fragments of the Holy Cross amount to less than one-ninth of its original volume. The history of the Holy Cross begins with Constantine the Great, the Roman emperor famous for having granted religious freedom to all Christians in 313. At this time there was a belief, kept alive by the Christians of Jerusalem, that the material evidence of Christ’s crucifixion was buried there.

Constantine, the first Christian emperor of Roman history, sent his mother, Helena — who is regarded today as a saint by both the Catholic and Orthodox Churches — to Jerusalem. On September 14, which would become the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, she discovered three wooden crosses and three nails in an old cistern not far from Golgotha, where Christ was crucified.

She divided Jesus’ cross into three pieces, to be sent to Rome, Constantinople and Jerusalem. Even the titulus, stating “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews,” as stated in St. John’s Gospel, was divided into two pieces. Upon her return to Rome, she converted a part of her house into a chapel, to host the relics she brought to Rome: a fragment of the cross, the half of the titulus and three nails. Today, this is the site of the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem, although in 1629 some of the relics were transferred to the newly constructed St. Peter’s Basilica by Pope Urban VIII.

The other two parts of the cross mentioned above were divided again into smaller parts, currently spread throughout Europe. In the past it was common to divide a relic into smaller fragments, according to the belief that even the smallest fragment had the same sacred power as the whole relic.

In Jerusalem, after St. Helena found the cross, pilgrims were allowed to kiss the piece left there. Beside the relic, they needed to put in place a person as staurophylax (“custodian of the cross”) in order to prevent pilgrims from taking a little piece of the cross with a bite!

2. The Holy Nails

How are we to establish which are the true ones, given that there are 36 “holy nails” in Europe, but only three of them nailed Jesus to the cross? Unexpected help came in 1968 from an archaeological discovery near Jerusalem. Four tombs were excavated and found three nails near the body of a young man, crucified supposedly between 6 and 65 A.D. They are rectangular in shape, 16 centimeters long and 0.9 centimeters wide at their thickest point. The comparison suggests that some “holy nails” are not genuine, since some are too long or made of silver.

Let us take into account the oldest sources, according to whom Helena discovered three nails of Jesus’ cross in Jerusalem. The first one is venerated today in the Roman Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem. The second nail was brought to Constantinople in 1354 by a Venetian merchant, Pietro Torrigiani. Pope Innocent VI was interested in acquiring the precious relics, but his offer was lower than the one made from Siena, by the rector of the Santa Maria Della Scala Hospital. Since the canon law forbade the trade of relics, Torrigiani signed a deed of donation to the hospital, but in reality, they rewarded him very generously “under the table.”

The fate of the third Holy Nail of St. Helena is more difficult to clarify. According to Theodoret of Cyrus, a part was embedded in the helmet of Constantine, while another part was melted into his horse’s harness. There are two places now where the emperor’s harness is venerated. The first is in Carpentras, France, the second in Milan, Italy. In 1576, Bishop Charles Borromeo, a leading figure of the Counter-Reformation, carried the relic three times through the streets of Milan, praying for the end of a deadly plague. Since the plague ended, they had no doubt: The holy nail made the miracle.

3. The Longinus Spear

According to the legend, the Roman soldier, Longinus — his name as referred to by ancient Christians — was cured of cataracts when he pierced the side of Jesus on the cross and the blood and water flowed out. Longinus was later baptized and martyred.

Pilgrims reporting from the Holy Land mention his spear up to the eighth century, not later. The history of this relic goes on from Constantinople. At the time of the Fourth Crusade, in 1204, Franks and Venetians invaded Constantinople and stole many relics, but not the spear. The Latin Empire of Constantinople founded by the Crusaders was repeatedly threatened by the Greeks and Bulgarians. Therefore, the ruler, Baldwin II, was forced to sell to King Louis IX of France the spear staff, in order to collect resources to defend his Empire.

Two centuries later, Constantinople was invaded again, this time by Ottoman Turks led by Mehmed II, on May 29, 1453. It meant the end of the long history of the Byzantine Empire. In 1492, Sultan Bayerid II proposed an agreement to Pope Innocent VIII: to welcome the sultan’s brother, Cem, a dangerous pretender to the Ottoman throne, to Rome. The agreement was that the brother had to remain in Rome in exchange for the return of the Longinus headspear.

The relic arrived in Rome from Ancona, an Italian city on the Adriatic Sea, delivered by two eminent cardinals. Pope Benedict XIV, in the 18th century, had many doubts on its authenticity. He asked the King of France to send the spear’s staff to Rome to verify the authenticity. The two pieces fit together perfectly.

4. The Pillar of Scourging

Given the huge number of relevant historical and religious sites in Rome, someone could ignore the small Basilica of Santa Prassede, dating back to 822, decorated with marvelous Eastern-style mosaics, located not far from the famous Marian Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore (St. Mary Major).

Here you could venerate one of the most relevant relics related to the passion of Christ: the Pillar of Scourging, made of Egyptian marble, whose shape is the same as the architectonic style of the Hellenistic age.

There is no evidence that the pillar is the one at which Jesus was beaten and scourged in Pilate’s praetorium; nevertheless, it is very likely. The first mention comes from the journal of Egeria, a pilgrim who visited the Holy Land in the late fourth century, who observed, “Many devotees went to Zion to pray before the pillar at which Jesus was scourged.”

It’s worth noting that in this place, Mount Zion, outside Jerusalem’s walls, there was a temple of the Judeo-Christian community. They preserved many Old Testament traditions, beliefs and precepts neglected by other Christians, including the prohibition of any contact with bodily remains within the city walls. Therefore, the pillar did not transgress any rule.

In 1009, Caliph Al-Hakim ordered the destruction of the Church of the Apostles, where the pillar had been moved. To avoid destruction, it was brought first to Constantinople, then Rome in 1223, thanks to the papal legate to Constantinople, Cardinal Giovanni Colonna. The rulers of the Latin Emperor gave him the pillar as a gift for Pope Honorius III in order to get his support. The cardinal very happily accepted the gift, since colonna in Italian means “pillar,” and in his crest, there was precisely … a pillar!

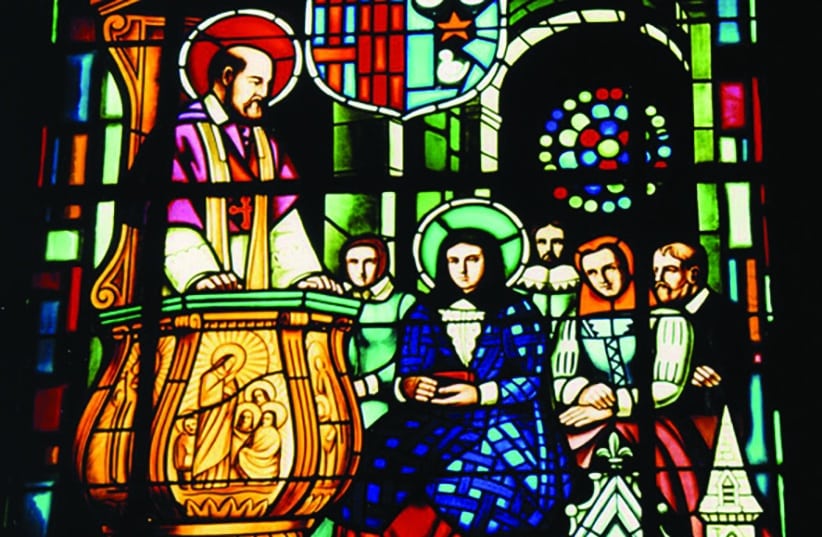

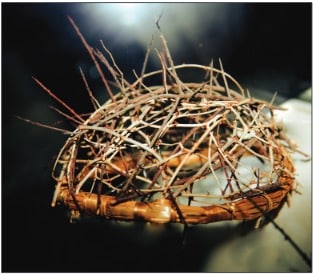

5. The Crown of Thorns

In 1870, Charles Rohault de Fleury, a French architect, counted 139 thorns throughout all Europe venerated as belonging to Christ’s Crown of Thorns. At least half of them are fake relics on the basis of the studies carried out in Paris, where the true crown has been located for almost 800 years. The hoop of the crown, about 12 centimeters large, is made of Juncus balticus, a plant species typical of the Eastern Mediterranean basin. According to some botanists, in the crown there were no more than 50 or 60 thorns.

There is a noteworthy clue in favor of the authenticity of the thorns: In the famous Turin shroud, scientists discovered a very high concentration of pollen grain from Gundelia tournefortii, a species of thistle only found in Judea, around the head area on the linen. This same thistle is one of the plants used in the Crown of Thorns.

was rescued from the Notre Dame cathedral fire on April 15.

When Jesus was taken down from the cross, it is likely that a disciple took the crown, hiding it somewhere in Jerusalem, where it remained a secret until the Roman Emperor Constantine granted religious freedom to Christians in 313. Then in 1063, the Byzantine emperor Constantine X ordered the crown be moved to Constantinople. Since Constantinople became the capital of the Latin Empire in 1204, many invaders have assaulted the city. Therefore, in order to pay military expenses, King Baldwin II was forced to accept the offer of the French King Louis IX: 135,000 pounds in gold, an enormous price, for the Crown of Thorns.

The financial situation of the Latin Empire was very poor. The crown previously was given to a Venetian banker, Nicolò Querini, as collateral in exchange for a big loan. Therefore, Louis IX sent two Dominican monks to Venice to prevent Venetians from fraudulently exchanging the authentic crown with a forgery.

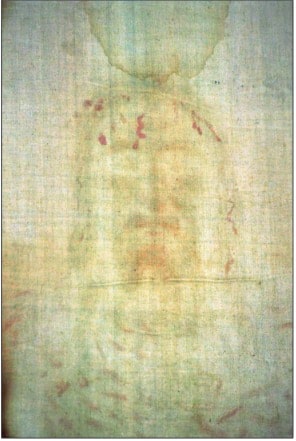

6. The Shroud of Turin

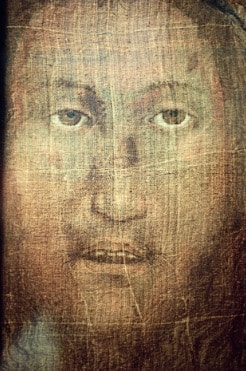

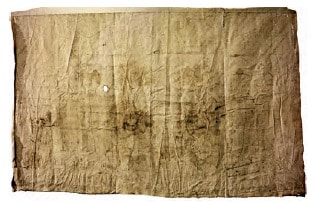

The most famous and venerated relic of Jesus Christ is an enigma that challenges the most advanced scientific knowledge, a simple linen sheet with an imprinted mystery, capable of justifying the religious belief of millions throughout the centuries.

Before the results obtained in recent times by sindonologists — namely, the experts of this new scientific discipline — the Gospels tell that Jesus, taken down from the cross, was wrapped in a linen sheet before being taken to the tomb. John tells of when, on Easter morning, Peter, having entered the tomb, saw the bandages on the ground and the shroud folded in another place. A millenary tradition of faith identifies that shroud with the precious relic that arrived in Turin in the 16th century after countless adventurous events between Edessa, Constantinople, France and Piedmont.

Whoever has the privilege of admiring the shroud during one of the rare public displays sees a single piece of linen cloth, herringbone fabric, 4.37 meters long and 1.13 wide. On the cloth are visibly imprinted the frontal and dorsal images of a human body with various wounds and injuries. Science has never determined how the images appeared. Various traces of blood are also recognized, first of all on the hands, feet and ribs. All the data obtained from the observation of the cloth extraordinarily coincide with the Gospel narration.

The shroud always has been the subject of extraordinary veneration and also heated scientific debate. No other item has been the subject of such a systematic examination involving a wide range of disciplines, from history to genetics. Despite the carbon-14 test, carried out in 1988, which traced the shroud back to the 13th or 14th century, many tests and researchers support the possibility of authenticity.

At least one point is clear: Even if the truth of Christianity does not depend on the shroud, the mystery hidden in it will never cease to fascinate.

7. The Holy Coat

Even if the authenticity is not yet proven, the history of the Holy Coat is full of surprising and interesting events, starting with three mysterious, bolted-shut chests discovered in Trier, Germany, on April 14, 1512, in a hidden chamber hollowed under the cathedral floor.

The discovery quickly excited everyone, given an old legend suggesting that Christ’s vestment was hidden in Trier Cathedral. Even the Emperor Maximilian was in Trier, eight days later, when they opened the chests and found in the first the relics of St. Maternus, an old bishop of Trier; in the second a knife (possibly from the Last Supper) and a die (suggested to be the one used by the Roman soldiers to cast lots for Christ’s robe); in the third, finally, a folded garment.

Immediately, Trier became such a popular pilgrimage destination that even Luther reacted very angrily: “What devil organized the world’s largest bazaar here, selling countless miraculous tokens?” he said, as historical sources refer. Maximilian was accused of having created a fake relic to strengthen his imperial authority, too.

It is worthwhile to recall that the Cathedral of Trier is the oldest German church, built under the order of Constantine, the Roman emperor. There is also a biography of Bishop Agritius of Trier, written between 1050 and 1072, stating that St. Helena, the mother of Constantine, returning from her famous trip to the Holy Land, donated several relics to Agritius, included a knife from the Last Supper and the Holy Coat.

Regardless, it was enough for the two million pilgrims who came to Trier in 1891 to venerate the relics, since the Holy Coat was very rarely displayed. In 1933, when the coat was put on public display again, the pilgrimage turned into a demonstration against the Nazi regime.

8. The Veil of Manoppello

The discovery was made by a German nun, Sister Blandina Paschalis Schlӧmer, not by an expert scientist. Her curiosity was captured by the photo in a newspaper, Das Zeichen Mariens, dated 1978. It was the Christ image on a veil housed in a small Capuchin shrine in Manoppello, a nice but unknown Italian town on Mount Maiella, far from Rome, about two hours by car.

The photo immediately reminded her of something, but she didn’t realize what. After some time, it was clear: There was a resemblance to the face of Christ on the Shroud of Turin. After some investigation, she found that if you put one over the other, the Manoppello image and the face impressed on the Shroud of Turin, all the anatomic details and the traces of the wounds, matched perfectly.

matches the Shroud of Turin.

History tells that in Middle-Age Rome, the most popular attraction for pilgrims was “the Veronica,” namely a veil so-called because, according to tradition, it was used by St. Veronica to wipe the face of Christ on Calvary. It is likely that the Veronica was originally the Veil of Camulia, a town situated in modern-day Turkey, which arrived later in Rome through Constantinople. Pope Innocent III instituted the tradition of parading the Veronica throughout the streets of the city, followed by giving alms to the poor to buy bread, meat and wine to celebrate.

In the 16th or early 17th century, the veil disappeared in unclear circumstances, while the first historical mention of the Veil of Manoppello dates back to 1608. The mystery is dense, because science and history have not yet given a definitive answer. What is certain is that the image visible on the veil could not have been painted by man. The similarity with the Shroud of Turin suggests that both the relics come from Christ’s sepulcher. When did the two perfectly overlapping images form? The only possible answer is when the depicted body was lying there.

9. The Sudarium of Oviedo

The Sudarium of Oviedo is considered by Catholics to be one of the burial clothes of Jesus. Apart from its first owner (St. Peter) mentioned by some early Christian authors, we know nothing for certain about the Oviedo sudarium until the seventh century. After supposedly being hidden somewhere in Jerusalem, when the Persians invaded the city in 614, it was brought first to Alexandria, Egypt, then to Spain two years later when Alexandria, too, was assaulted by Persians. The trip of the sudarium continued through Cartagena by sea voyage, then Sevilla and finally Toledo, the see of the primate of Spain.

The ups and downs were not yet over. When the Arabs invaded the Iberian Peninsula, many Christians escaped toward the north, carrying the sudarium with them. It then was buried in the peak of Monsacro, in the Asturias region, and unearthed only half a century later, to be moved to the regional capital of Oviedo. As a result, the cathedral of that city became an important pilgrimage site, thanks also to the fact that it was on the way to Santiago de Compostela.

Nothing relevant happened until 1934, when left-wing terrorists blasted dynamite in the cathedral crypt. The explosion destroyed the entire place, but the sudarium was not destroyed. The crypt was restored in 1942, and the sudarium remains there presently.

It is a linen cloth measuring 84 by 53 centimeters, with visible traces of blood. It likely was folded in half before being wrapped around Jesus’ head. In recent times, many examinations offered interesting results in establishing the authenticity of the relic.

The cloth dates back to the age of the Roman Empire. There are many traces of myrrh and aloe, used at that time to anoint the corpses to slow the decomposition process. There are bloodstains coming likely from the wounds caused by the Crown of Thorns.

Let us consider also the comparative studies between the Sudarium of Oviedo and the Shroud of Turin. Even if carbon-14 tests date both these two relics to the Middle Ages (but at the same time there is proof that these tests have at times been inaccurate), it is difficult to suggest they are not authentic to Christ’s death. How else could one explain how they could have the same blood type, the same size and arrangement of the wounds, with the traces of the same pollen seeds — evidence that makes authenticity difficult to dismiss.

10. The relics of Aachen

According to some ancient sources, the emperor Charlemagne collected several relics of Christ’s passion, including many burial clothes donated to him in 799 by the patriarch of Jerusalem.

St. John the Baptist are in Aachen, Germany.

This is likely because Jewish burial customs needed many clothes, all the more in the case of Jesus. His body on the cross was very bloody. According to the belief of this age, every contact with blood or a dead body made a person unclean. This is the reason sindonologists suggest that a second shroud, in addition to the Turin one, was used in taking Jesus down from the cross and moving him to the sepulcher.

During the time of Charlemagne, relics were stored in Aachen, Germany, Western Europe’s most important city at that time. Four so-called “great relics” of Aachen are preserved today in the local Cathedral of St. Mary. They are the Virgin Mary’s cloak, Christ’s swaddling clothes, St. John the Baptist’s beheading cloth and Christ’s loincloth.

Can they be considered authentic? They have never been examined using scientific methods like bloodstain or pollen-grain analysis. The restoration made at the end of the past century revealed that all of them originated in the Middle East during the age of the Roman Empire. The cathedral’s clerics do not judge the relics to be authentic, given the lack of strong evidence. But no one, at the same time, could deny their importance as symbols in the history of the Christian faith.

| Want to Read More? |

|---|

|

“Witnesses to Mystery: Investigation into Christ’s Relics” (Ignatius Press, $34.95) by Grzegorz Gorny and Janusz Rosikon explores each of the relics associated with Jesus’ passion, death and resurrection. Over a two-year period, writer Gorny and photographer Rosikon visited museums, archives and churches, talking with historians and scientists in order to provide this rich text detailing the record of each relic, their impact on Christianity, and the authors’ conclusions of the authenticity of each holy item. The work is published in various languages, including the English version from Ignatius Press. Much of the main body of this article comes from the book itself, as well as the photos, courtesy of the Polish publisher, Rosikon Press. |