(OSV News) Eight hundred unique photographs of the Ulmas remain precious memorabilia in family and state archives. They tell a story of the joys and hardships of their everyday life. But they also tell the story of those they tried to save. Who were Wiktoria and Józef Ulma, and who were the Jews they were sheltering?

“Their house was very modest, it was a wooden cottage,” Sister Maria Szulikowska, who has written several books on the Ulma family, including “Wiktoria Ulma — The Story About Love,” told Polish Television, or TVP.

The house seen in several pictures is neither big nor very solid, made from modest wooden materials.

“It really had only one room. Józef put a closet in the middle to separate the dining room from the bedrooms,” Agnieszka Bugala, author of the book “The Ulmas — Righteous and Blessed,” told OSV News.

It did have lots of light from “beautiful venetian windows,” added Maria Ryznar-Folta, director of the Society of Friends of Markowa. And two things were never lacking.

“One can’t understand the Ulma house without faith and without love,” Sister Maria said.

Life with the Ulmas

Józef was a modern gardener. He introduced growing vegetables in the village, he was a beekeeper and silkworm breeder. Wiktoria was attending a course at the People’s University; at some point she even played Virgin Mary in the local theater.

Józef loved photographing his wife. Before their marriage she appears shy in a spring photograph taken in their trench coats after their wedding announcements in the parish church. Józef is smiling widely.

“Look how happy he was, having a woman he loved so much next to him,” Ryznar-Folta told OSV News, pointing to a photograph from May 1935.

Józef, a man full of ideas

“Wiktoria was a silent woman and Józef was totally different. He was an extrovert full of ideas,” Bugala said. “But you can’t tell she was a housewife and he was a rock star. No, they were true partners. He wanted to marry Wiktoria because she was intelligent, beautiful, and she was supporting him in his innovative ideas. I mean, we’re talking about a man that was the first one in the village to have an electric bulb in his home so that he can read at night. And Wiktoria was reading a lot too, not many housewives signed up for a university course at that time of Polish village life history!” she stressed.

“Young people that I meet today are shocked. ‘Don’t tell me she had a university diploma!’ they say. Well, there was no diploma, but it was extraordinary that she got to know the academic environment,” Sister Maria said.

Photographs allow a glimpse into family life

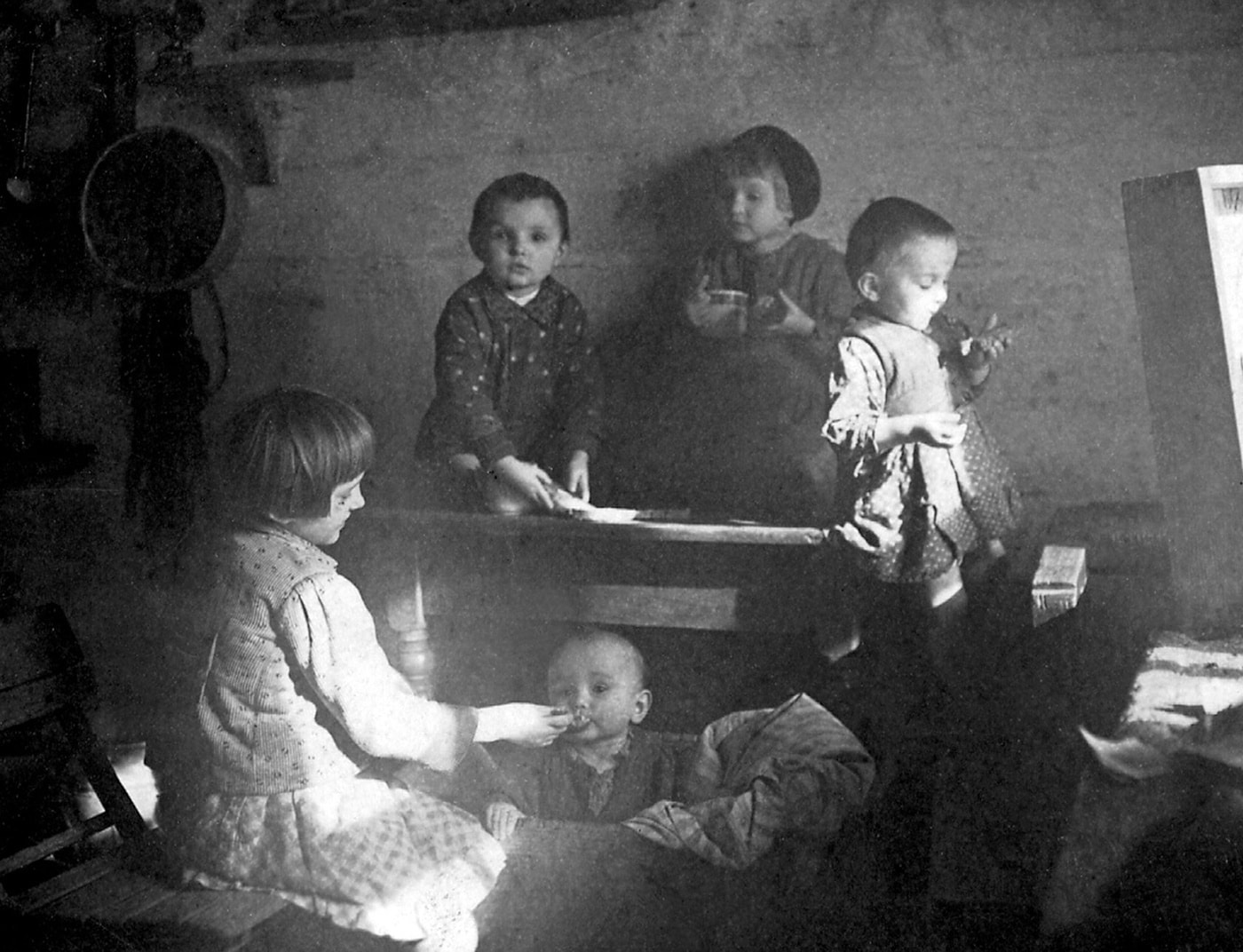

Józef was a volcano of ideas. He constructed his first camera on his own. Pictures he took show a home that was loving and happy in very ordinary things — baking, farming and helping with homework. Children are seen eating, walking with their mother, learning how to write, playing or helping their mother.

“The children fed each other, the children participated in Victoria’s chores. There is one photograph in which the kids give Wiktoria laundry, she hangs it up, and she is so happy that she already has the help of the children. They just grow into the world,” Ryznar-Folta said.

“There is a picture of Józef’s father sitting on a wooden block and reading. Józef was doing the same; he had an impressive library. And his children were copying daddy and grandpa — in one of the pictures one of the children is seen eating and next to the child there is an open book!” Sister Maria said.

“Their everyday life told by Józef’s pictures is the biggest heritage that the Ulmas left us. The everyday love they shared, the life they lived. Their martyrdom is important, yes. But for me, it’s the life lived that speaks volumes — for me it’s the biggest lesson the Ulmas give us,” Bugala said.

A Jewish family asks for help

Four years after Wiktoria and Józef were married, in 1939, World War II started and Poland fell under German occupation. By 1942 the occupiers were organizing manhunts as no Jew was allowed to live outside the ghetto.

“From the summer until the late fall of 1942, the hunt for Jews in Markowa continued. Those found walking down the street or standing in front of a house were shot on the spot — without warning. Those who tried to hide were dragged out of dugouts, barns and pits dug in the fields. Old men and children, women and men were killed. People were hunted day and night,” Bugala wrote in her book.

That’s when the first Jewish family asked Józef and Wiktoria for help. Józef prepared a dugout on the field full of grass, and Wiktoria secretly provided fresh water and food for a woman named Ryfka, her two daughters and granddaughter.

Unfortunately, the three women and a 1-year-old girl were found and executed in a Nazi manhunt Dec. 14, 1942, Bugala wrote. After killing two young women, the Germans allegedly were hesitant to kill a little child, so they asked the grandmother to come in and out from the dugout three times before they shot them both.

Józef took a picture of the two younger women with the child before they were executed.

In late 1942, after Maria, the Ulma’s sixth child was born, manhunts organized by the German occupiers became so visible and frequent that Saul Goldman, a cattle seller from Markowa, came to Józef and Wiktoria and asked them to help hide his family.

“Most probably he came first with his sons and later his adult daughters joined, or the other way around, because it’s highly improbable that they would just march like that, eight people, to the Ulma house, at once,” Bugala said.

Polish patriots

She also emphasized that Jews from Markowa were Polish patriots. One of Goldman’s sons was defending the country in September 1939, when the German invasion started, followed by the Russian invasion from the east 17 days later. People in Markowa treated Jews as part of their community, as Polish citizens, their neighbors, business partners and friends being unjustly chased and inhumanly killed.

“The amazing thing about Józef and sheltering Jews was that he wanted to bring those people dignity. And work brings back dignity. So he tanned leather along with the Jewish young men hiding in his house. Thanks to it they could get out from the shelter from time to time,” Bugala said.

One of Saul Goldman’s adult daughters was Golda Grünfeld. She was Wiktoria’s school friend. Her sister, Lea Didner, sheltered in the Ulma house with her 3-year-old child, most probably a girl named Reshla.

Józef could buy food for the leathers he tanned as his family technically doubled and there were seven more adults to feed. People of Markowa say that the couple would prepare dishes that the Jews were allowed to eat by their religion. Some family members recalled that “they lived with the Ulmas like the family,” saying that both families — Catholic and Jewish — would pray together.

Betrayed months before occupation ended

The Ulma house was located farther away from the center of the village so the Ulmas thought that they were safe. They were denounced three months short of German occupiers leaving Markowa.

On March 24, 1944, around 4 a.m. German lieutenants arrived at their house under the command of Eilert Dieken.

“They immediately murdered three Jews still inside the house, then went outside, and later led the Ulmas out and killed Józef first, then Wiktoria Ulma, who was in the last stage of her pregnancy,” said Mateusz Szpytma, relative of Wiktoria and historian who told their story to the world.

Then they shot all six children, ages 1 to 8. Witnesses said Wiktoria started to give birth after she was murdered. German commanders decided to kill the kids so that the village “is not bothered with them,” in their own words.

“It was something extremely dramatic when you read what happened: the yells, the screams. The youngest gendarme, and at the same time the most cruel, Josef Kokot, shouted while murdering them, ‘That’s how Polish pigs who hide Jews die,'” he said.

House looted, pictures left behind

When all of the people in the house were shot, German officers started to loot the house. Pictures were not valuable to them so they tossed them on the table.

One of the pictures found by the family relatives after the crime was that of Ryfka’s daughters, women who sheltered earlier in the field dugout. Blood of the Jews killed in the attic was dripping down on the table where the picture was laying. The blood of Jewish guests of the Ulma family, martyred along with their hosts, is still visible today on the photograph.

Cardinal-designate Grzegorz Rys said in an interview with KAI Polish Catholic news agency that although the Ulmas could not save the eight Jews they were hiding they however “saved humanity.”

“They saved humanity – also for us. And whether this death — of Józef, his wife and seven children — is fruitful, will only be seen in us.”