Harvard Law School professor Mary Ann Glendon served as U.S. ambassador to the Holy See during the final year of President Bush’s second term in office. In the following conversation with Our Sunday Visitor, the ambassador shares her fond memories of Pope Benedict XVI’s historic 2008 visit to the United States and reflects on the pope’s warm relationship with President Bush. Ambassador Glendon offers insight into the late pope’s resignation, discusses Pope Benedict’s view of women leaders in the Church, sheds light on the controversial Regensburg address, and considers Pope Benedict’s legacy.

Our Sunday Visitor: What was your reaction to the invitation to serve as the U.S. ambassador to the Holy See? What was that moment like when you entered the role?

Mary Ann Glendon: Well, I can tell you that I did not expect getting a phone call from the White House that summer asking me if I would like to be the ambassador. Reflecting now, I think what I should have said was, “Well, I’ll have to think about it. I’ll have to discuss it with my husband.” But I said, “Yes, I’d very much like that.” For one thing I knew my husband would be just as happy as I was, and for another, you know I’m an academic, but like many other faculties, Harvard Law School really likes to see its professors in public service. I had served on governmental commissions before, and I thought it was a good thing to do for the Church and for my country and for my students.

The call came completely out of the blue. I had absolutely no inkling. I had of course served President Bush in other capacities and along with Father [Richard John] Neuhaus and George Weigel, I had met with him from time to time.

Visit to the U.S.

Our Sunday Visitor: One of the most exciting things, I think that this is correct to say, that happened during your tenure was welcoming Pope Benedict XVI to the United States. What was it like working to organize this visit? Did the things that you really wanted to witness come to fruition? Were there any moments that you thought definitive for the life of the American Church?

Glendon: The 2008 visit to the United States was Pope Benedict’s first and only visit as pope, and it was the very first thing that I and my staff at the embassy had to prepare for. When I presented my credentials, we were only a couple of months away from the visit.

There were many memorable moments about that visit because it was, as you know, extraordinary that there had been a previous meeting between Pope Benedict and President Bush only a few months before in June of 2007. It was clear to observers that a very cordial relationship had developed between the president and the pope. It surprised many people because their personalities were so different.

I think a symbol of how extraordinary that improbable relationship was is that the president and I and other peoples went out to Andrews Air Force Base to meet the pope upon his arrival. This was the first and only time that President Bush had ever gone out to meet a foreign head of state. I was so fascinated by the fact we were standing around, waiting for the pope’s plane to land. Somebody asked the president, “How come you’re coming out here to meet the pope?” And President Bush replied, “It’s very simple. He’s the greatest spiritual leader in the world.” In fact, when the pope got off the plane and the two of them sat down for a few minutes to talk and have some orange juice, President Bush said, “Your Holiness, people have asked me why I came out here to meet you, and I tell them it’s because you are the greatest spiritual leader in the whole world.” So it was clear to me that the relationship had already gotten off to a great start.

But coming back to your question about highlights or particular moments in the trip … it was a whirlwind visit. There were 16 speeches by this pope in five days, but there are two that really stick in my memory. One was the ceremony on the White House South Lawn. It was the pope’s 80th birthday that day, and what was so touching was that when the president mentioned that this was the pope’s birthday, the whole assembled audience burst into singing “Happy Birthday.” And the pope, despite his wonderful success as a public figure, kind of just shyly smiled and then raised his arms and with a big smile on his face. When the president and the pope then exchanged remarks, it was like a duet. Both leaders sounded the same themes: freedom is a precious thing that requires work to keep alive, and a free society and a decent society is one which cares for the weakest and most vulnerable. It was a beautiful, touching occasion.

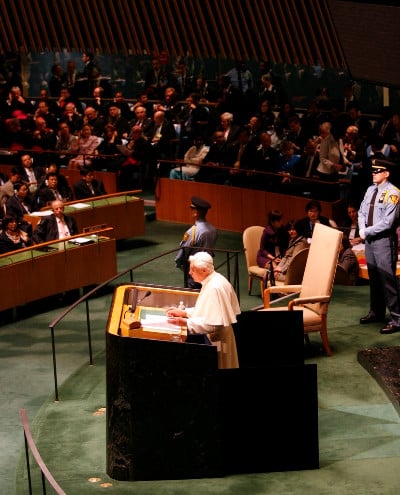

The second event that I thought was really historic was the speech to the United Nations. You know I have a special interest in the fact that it was the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The pope began, like his predecessors, by praising that document as a great event in human history, but then he went on to deliver the most penetrating critique of the manipulation and misunderstandings of the human rights project in recent times. In view of that it was somewhat surprising that he received a standing ovation from that packed hall — the whole General Assembly was standing room only. Afterwards it occurred to me that even though his remarks were surprising, I think the diplomats there, those worldly folks, I think it was a relief to them to listen to somebody who spoke as a moral witness. They must have known that they were listening to somebody who, like all Holy See representatives, was charged to speak and act for the good of humanity, not just for the sovereign entity he represented and not just for Catholics. I think it was a relief for them to hear someone speak that way.

The legacy of Benedict XVI

Our Sunday Visitor: Following Pope Benedict’s visit to the United States, President Bush paid the pope another visit at the Vatican. It seems even more remarkable because of the tensions between the United States and the Holy See concerning the American-led invasion of Iraq. What themes or interests did they share that belong to Pope Benedict’s legacy?

Glendon: When the war in Iraq was concerned, there had been a considerable amount of tension between the United States and the Holy See. But by the time Benedict became pope, the situation had changed. Pope Benedict was focused on looking ahead, rather than revisiting the disagreements that had caused that tension in the past. His main concern at the time I became ambassador was that an abrupt American withdrawal from Iraq would lead to increased instability and persecution of Christians and other minorities not only in Iraq, but also in other parts of the Middle East. We absolutely saw this as events developed.

That was the background of the cordial relationship that developed between President Bush and the pope. Another factor was that the pope was aware of the president’s deep Christian faith. They had many shared commitments, and the main topics that they discussed included, for example, strengthening the moral consensus against terrorism, combating the use of religion as a pretext for violence, advancing peace in the Middle East, and concern for the plight of persecuted Christian minorities.

Our Sunday Visitor: Pope Benedict XVI widely and directly opposed the dismissal of objective truth in society, a cultural and intellectual tendency he dubbed the “dictatorship of relativism.” Looking back at the Holy Father’s work, from your own perspective in the academy, how do you think his ideas about objective truth are being received today? How will they stand in years to come?

Glendon: Well, I think he will always be recognized, along with theologians like Bernard Lonergan and others, as one of the leading thinkers on that subject. I think he had a gift for communicating about it that enabled him to reach a wider audience, but the argument will always continue.

Our Sunday Visitor: Many people have labeled Pope Benedict a professor and categorized him or written him off because of that label. Did you find that to be the case in your experience with Pope Benedict?

Glendon: Not at all. It is true that many doubted whether the man they knew as the shy and scholarly Joseph Ratzinger would be able to communicate effectively to diverse audiences in the public square. But I think he quickly and totally dispelled that idea with his great speeches. I think some of his very best writings were the relatively short speeches he gave in worldly settings, such as the British Parliament at Westminster, the German Bundestag, the Élysée Palace, the White House and the United Nations. Those speeches made it clear that he, like his predecessor, was going to use his public platform to be a global moral witness, and that he could talk about those great themes of human rights, religious freedom, and the synergy between faith and reason in a way that would make a deep impression on many secular minds. That’s what happened in Paris — the very cradle of secularism. When he finished the address there, Nicolas Sarkozy said, “But you are right, we have to rethink this whole concept of laicism.” All the British journalists expected that he would get a very chilly reception at the British Parliament at Westminster. In the end he was welcomed warmly. People like to hear somebody who speaks clearly and consistently about the great issues of our time.

One of the things that happened at the outset of Pope Francis’s election was that he was deemed the great innovator of the papacy. That’s how he was cast in the mainstream media. But Pope Benedict was himself a pope of many firsts. Right from the outset, for example, on his coat of arms, he replaced the papal tiara with a simple miter. I mean, there were many small signals. He carried his own briefcase, for example, after his election, just like Pope Francis. There were many signs of how he was going to imagine himself as a servant first.

Our Sunday Visitor: Were you surprised at Pope Benedict’s resignation?

Glendon: Not at all. Unknown to most of us at the time, he immediately faced huge crises in the areas of sexual and financial misconduct. Very few people realized what a burden had been placed on those frail, rather elderly shoulders when he became pope.

I recall when I presented my credentials to him when I arrived in Rome. There is a moment in that ceremony where just the pope and the new ambassador have a private conversation. Most of what we talked about was the difference between academic life and public life. This is just my interpretation, but I felt that there was a certain nostalgia in his voice, but I had no idea at that time what he would face.

I remember there were all sorts of theories about why he would do such a thing, but by that time I had a better understanding of what he was dealing with because he had asked me to chair a committee, a State Department committee, on the possibility of litigation against the Holy See in the United States. From that vantage point, I had a pretty good idea of what he was contending with. And so I took his own statement at face value, that he had come to the knowledge that his strength and the burdens of age were no longer suitable for administering the Petrine Office.

Women in the Church and the address in Regensburg

Our Sunday Visitor: Today there are many questions about women and the positions of authority they hold in the Catholic Church. As a woman who has held significant leadership positions in the Church, what do you think were Pope Benedict’s contributions to empowering women?

Glendon: I think his views were very similar to those of his predecessor, who as you know did not hesitate to appoint women, including myself, to leadership positions. I think he would have done more along those lines, if he had not had to deal with so many crises. It was Pope Benedict, for example, who insisted that L’Osservatore Romano — which had never had a female reporter until 2012, can you imagine? — give women more space in the paper. This resulted in the hiring of prominent Catholic feminist Lucetta Scaraffia. She then became the editor of a monthly supplement to the newspaper and brought with her a team of all women. So while his personality was less expansive than that of John Paul II in this regard, I think his views were very similar. He certainly was comfortable with women theologians. He re-appointed me, when I finished my ambassadorship, as president of the Pontifical Academy for Social Sciences. I think he was disposed to do more, really, but was simply overwhelmed by other things.

Our Sunday Visitor: Pope Benedict delivered a very controversial address in Regensburg, which because of his citation of a historical critique of Islam, sparked violence and opposition throughout the Islamic world. What do you make of the continued reception of that speech?

Glendon: I went to a meeting in November, where, at the G20 for the first time, there was an organized forum for religion held before the meeting. I was there for this meeting, dubbed R20, and I had occasion to hear many talks by the leaders of the world’s largest Islamic political association. It’s called Nahdlatul Ulama and it has 100 million members who subscribe to a form of Islam that embraces religious freedom and rejects the use of religion as a pretext for violence. Interestingly, this movement looks to Vatican II as a model for how Islam can examine its past and leave behind things that are not necessary to the core of the faith and move ahead. Everything that I heard from the leaders of Nahdlatul Ulama reminded me not so much of Vatican II, but of Pope Benedict’s speech at Regensburg. At the time of the speech, the people who covered his remarks zeroed in on his quotation of an anti-Muslim remark by a 14th century emperor. However, the essence of Benedict’s message at Regensburg was that Islam needed to go through something like Vatican II to be able to confront secularism and move ahead in a way that retained continuity with the essence of the faith.

It was clear to me at R20 that the leaders of Nahdlatul Ulama had carefully read the address at Regensburg and that they, unlike most of the reporters who covered it, understood the central message, which was a warning about the disturbing pathologies that occur when religion and reason divorce, when faith and reason are separated. There was no reference to Regensburg, but nevertheless I had a strong impression that that speech was really appreciated by the leaders of the largest Muslim organization in the world.

Our Sunday Visitor: By way of conclusion, what aspects of Pope Benedict’s legacy do you think will best weather the judgments of time? How do you think people will look back on this papacy?

Glendon: I think that he will be remembered as a great theologian, and that goes back to his participation in Vatican II. Many people like a story about Pope Benedict that he was a liberal theologian way ahead of his time, who became conservative in later years. I think that shows that they have not read much of Joseph Ratzinger / Pope Benedict’s work, because the fact is that there has never been a pope who has been so explicit about the need to welcome the positive aspects of modernity. Think of his many references to what he called the good gifts of the Enlightenment, the good achievements of modernity. He insisted on the synergy between faith and reason such that faith without reason easily becomes fundamentalism and reason without faith easily leads human beings into very dark places. What will he be remembered for as pope? He will be remembered as a great moral witness. He was someone who tried to carry forward the authentic spirit of the Second Vatican Council. He tried to maintain continuity with the truths that are ever ancient and ever new by bringing the Gospel message to the modern world in the public square.

Father Patrick Briscoe, OP, is editor of Our Sunday Visitor.