Is Pope Francis a populist? The simple answer is no. A better answer is necessarily more complicated.

Is Pope Francis a populist? The simple answer is no. A better answer is necessarily more complicated.

But, someone might ask, does it really matter? As a matter of fact, it matters a lot — at least if you’re trying to understand where this sometimes controversial pontiff wishes to lead the Church.

One reason why the question isn’t open to a simplistic response arises from the fact that “populist” and “populism” cover a bewildering range of individuals and political systems. In the United States, for instance, Andrew Jackson, Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders have all been called populists.

In general, populism is a way of doing politics that exalts “the people” in opposition to an “elite” said to be oppressing them — Wall Street, the denizens of the Washington “swamp,” segregationist populist George Wallace’s “pointy-headed liberals” or whoever it might be.

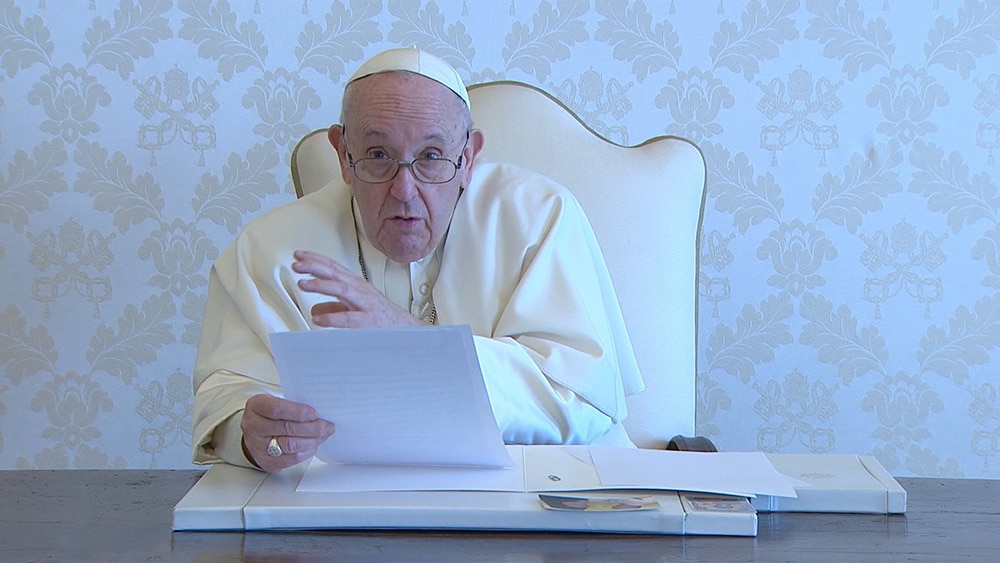

The question of the pope’s relationship to populism arises naturally in light of a conference in London last month (co-sponsored by the U.S. Catholic Campaign for Human Development) inspired by his recent book “Let Us Dream” ($26, Simon & Schuster). In a video message to the gathering, Francis called for “a politics with the people, rooted in the people.”

That has obvious populist resonances. Given populism’s mixed record, it’s fair to ask where the pope himself stands.

In Fratelli Tutti. the encyclical “on fraternity and social friendship” that he published last year, he presents a mixed picture: on the one hand, “popular” leaders who truly reflect “the feelings and cultural dynamics of a people” and, on the other hand, demagogues who exploit people for their own advantage or appeal to “the basest and most selfish inclinations of certain sectors of the population.”

The pope’s concern for these matters goes back years — in fact, all the way back to the late 1960s when he was a youngish Jesuit provincial in Argentina and Catholic thinkers there were developing what came to be called la teologia del pueblo (“the theology of the people”).

In a study called “The Roots of Pope Francis’ Social and Political Thought” (Rowman & Littlefield), political scientist Thomas R. Rourke speaks of the “reverential attitude toward” the people shaping this theological movement: “In Latin America, despite the negative dimensions of colonization, the simple faithful had in many ways throughout their history incarnated the Gospel in their culture.”

Although, as Rourke points out, Jesuit Father Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the future pope, was not an academic theologian, he shared this way of thinking. His attitude is suggested — though not in a political context — in a remark the author quotes: “When you want to know what to believe, go to the magisterium. When you want to know how to believe, go to the faithful people. The magisterium will teach you who Mary is, but the faithful people will teach you how to love Mary.”

A half-century later, Francis is still thinking that way. “The true response to the rise of populism is precisely not more individualism but quite the opposite: a politics of fraternity, rooted in the life of the people,” he told the London conference.

Populism, politics of fraternity — the danger is sentimentalizing “the people” while ignoring the fact that, in a demagogue’s hands, the people can be as self-absorbed and wreak as much havoc as any elite. Which may be why Francis felt is necessary to add this caution: “I like to use the term popularism.”

So, no populist is he, but a popularist. In his mind, there’s a big difference. Just how big may be the real question.

Russell Shaw is a contributing editor for Our Sunday Visitor.