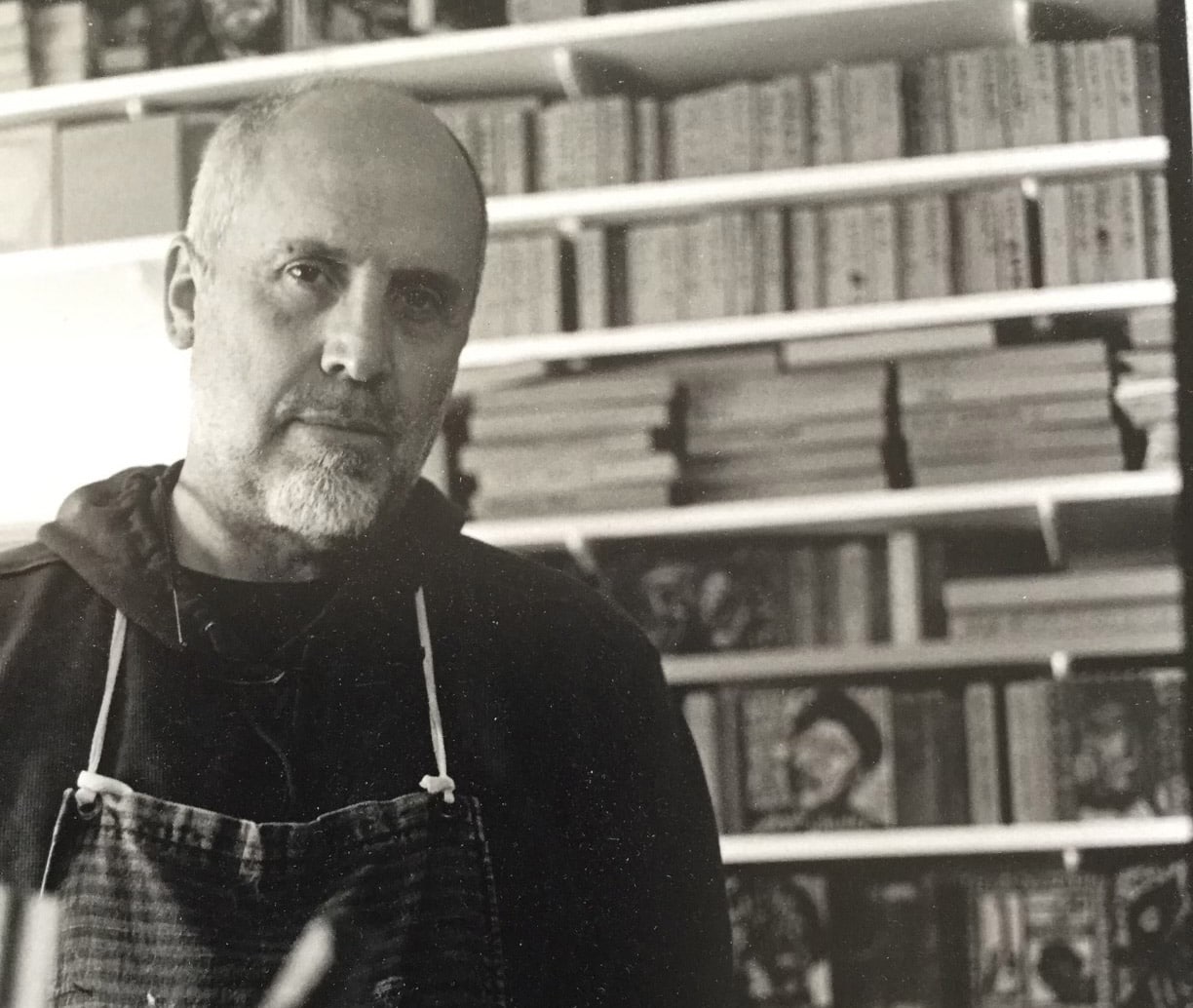

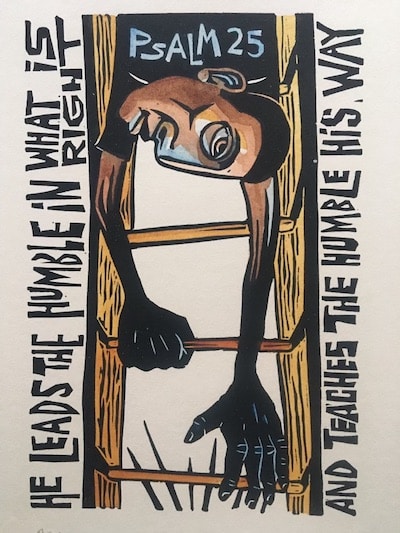

Kreg Yingst had set himself a task: He would make one block print for each of the psalms.

“I thought I was gonna knock it out in a year,” he said.

He did not knock it out in a year. Some of the images came to him easily, but some were a struggle. The project dragged.

And that was perfect.

“I had to wrestle with it. It became my daily prayer. If nothing came, I had to sit on it, and that would be the one prayer I would pray. If a visual didn’t come, I would read it tomorrow,” he said.

He compares the process to meleté, the intense word-based meditative prayer of the Desert Fathers. Many of them were illiterate, so they would go to their abbot, receive some lines of Scripture and immerse themselves in them all day to “pray without ceasing” in their cells, perhaps in song. This slow, repetitious meditation would purify their hearts and allow the words to take root.

More than two years later, Yingst’s prints that grew from these words became a book, “The Psalms in 150 Block Prints” ($35.95).

Yingst, 63, was heavily influenced by the black-and-white graphic woodcuts of German artist Frans Masereel and American Lynd Ward, whose wordless novels are considered a precursor to the modern graphic novel. Yingst’s deft, striking compositions, which often incorporate text, are sometimes exuberant, sometimes mystical and often jarring.

As an artist who shares his work on Instagram as he makes it, Yingst has had the disconcerting experience of knowing his most heartfelt pieces will probably be social media “duds.”

Messages of the psalms

“We all want to be happy, and we all want sunshine. It’s the sweet aroma of prayer that everybody likes,” he laughed.

But the psalms also carry a lot of darkness, struggle and fear. He chose not to skip over those verses.

“When the rainy days come, how do I deal with it? Because I can’t escape it. That’s what the psalmists were doing. They always came back to [saying to God], ‘You’re still here. You’re my rock, my foundation,'” he said.

At the same time, he learned that some of the more fearsome psalms — the ones begging God to crush our enemies, and the ones that speak of dashing babies against rocks, are not what they first may seem.

“I need to understand this is a spiritual language. I can’t let this bitterness take root in me but cut it off while it’s still a baby. I started reading the psalms that way,” he said.

He discovered that they’re not so much inveighing against an enemy that’s some literal group of people but against whatever darkness every human will encounter.

Carving light

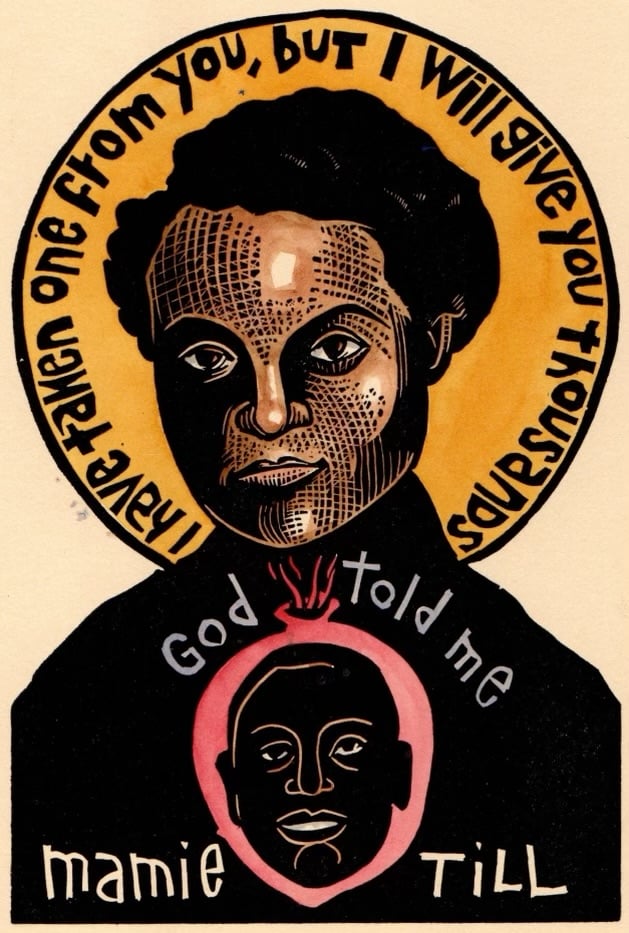

One especially dark moment was the school shooting at Sandy Hook in 2012. Yingst had two young daughters and couldn’t come to terms with the horror and loss those parents were enduring. So for his New Year’s resolution, he decided to carve one prayer a week for the entire year. Those images became a self-published book, “Light from Darkness: Portraits and Prayers” ($29.95), and he donated the proceeds to orphanages. Sandy Hook parents had lost their children, so he wanted to help children who had lost parents.

“It was reactionary. I wanted to throw light. At least, this will bring a little light,” he said.

Woodcuts and linoleum prints are particularly suited to that goal.

“With the block print, and with linoleum or woodcuts, you have that black square, and every time I make a mark, every time I make a gouge, I’m carving light out of darkness,” he said.

Each morning, he would begin searching for a prayer that dealt with light coming from darkness. Not all of his sources were explicitly Christian.

“It was kind of like a tree. Jesus was the first; [St.] Francis was the second. Then you start reading on Francis and who he influenced, and you check them out, and it’s a tree that starts to branch out,” he said.

In this book, he includes saints, but also Martin Luther, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and anyone else he found who spoke to this idea of a plea for light over darkness. But like the tree with firm roots, it always leads back to Christ. This continual return to Christ as the root of the tree, the center of the wheel, is the hallmark of Yingst’s work, including the pieces that aren’t overtly spiritual.

Taking root

Yingst was raised Lutheran but found himself drifting in his mid-20s. But one day, he was brought up short by a parable, the one about the sower and the seed. Some seeds fell on the path and were eaten by birds, some fell on rocky soil and didn’t grow; some grew quickly, but were scorched because the soil was shallow. Thorns choked some.

“I was able to identify with each one, except the one that took root. All the other ones, I had been, but not the seed that put down roots and grew,” he said.

Since then, he has attended numerous churches. He strives to learn from all of them, and to seek rootedness in Jesus.

“The common denominator is love for Christ, and God’s love for us,” he said.

For practical reasons, he keeps two different Etsy shops, one for sacred art and one for music-themed works; but he wishes it didn’t have to be that way.

“I don’t like the dichotomy,” he said.

Connections

Wherever he can, Yingst tries to make connections. When he sets up shop at art shows around the country, he will sometimes slip in a little sacred art among the woodcuts of Muddy Waters portraits or Beatles lyrics. He believes that most music has some spiritual element to it; and he has found that music, and visual art connected to music, often makes a common ground for people who would otherwise not be open to religious ideas.

While visual art rarely moves him to tears (only music has that power), his art seems to hit people hard, and to open them up in unexpected ways.

“I’ve had people come in and lay heavy stuff on me sometimes. A woman just about to walk out turns around and lets me know her son died last week, and she’s picking up Eric Clapton’s ‘Tears in Heaven.'” Or another one had Pete Seeger’s ‘Turn turn turn’ and said, ‘My mom used to sing this to me; she’s just been diagnosed with cancer,'” he said.

Yingst says he has seen fathers and sons connect over one of his prints; and he’s had the opportunity to pray with people.

“I think God touches on every aspect of our life. I don’t separate religious from secular. He wants to be in every aspect of our life, from our health, to the choices we make, as any good parent would. I see God as having both those qualities, father and mother,” he said.

Although Yingst makes his living traveling around the country selling his work at art shows, he would happily remain at home in Pensacola, Florida. But while silence and solitude naturally appeal to him, they were imposed on many against their will during the pandemic; so he intentionally sought out lessons from the hermits and the Desert Fathers and Mothers, to learn how they endured their time in the wilderness.

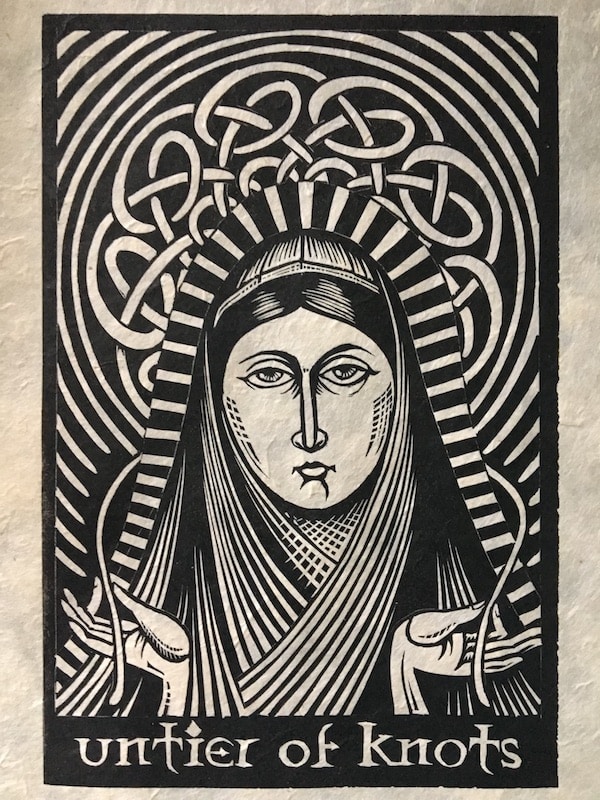

It was also during this isolation that he encountered the work of Christine Valters Paintner, and she asked him to illustrate her project “Birthing the Holy: Wisdom From Mary to Nurture Creativity and Renewal” ($18.95). This sent him deep into research to illustrate 31 of the titles of Mary.

“It was a history lesson for me,” he said.

Christ at the center

No door is closed for Yingst, as long as it might open to Christ.

“I feel like I’m the one to bridge the gap, to educate myself, and to find people who are wrestling in their own faith, and have found this connection in their own right, and to share that. I look at it as the tree. Jesus is the roots, and the stump began to grow when the Church was birthed. You have the schism with the East and the West and another split with the Protestants, and now you’re looking at a tree with a hundred tiny branches. But I like to think they can all trace back down to the root,” he said.

He’s currently working on the final stages of a book tentatively titled “Everything Could Be a Prayer: One Hundred Portraits of Saints and Mystics,” based on a quote by St. Martin de Porres. This book will be in color, and will draw on a wide variety of figures from different backgrounds on various spiritual walks, from hermits to Harriet Tubman. They will all have in common some point of contact with Christ.

“My whole lineage goes through Jesus. He was my contact point on that day 35 years ago. I called out, and he was that one that answered. He was the one who was my friend, my savior, and everything else. I come from a Christology, a cruciform. I see God through the cruciform Christ. He becomes the center of everything else,” Yingst said.