To reduce the residual shadows over the pontificate of Pope Pius XII (1939-58) will take time, given the vast number of documents on the pope and those tormented years of the Second World War and the Holocaust.

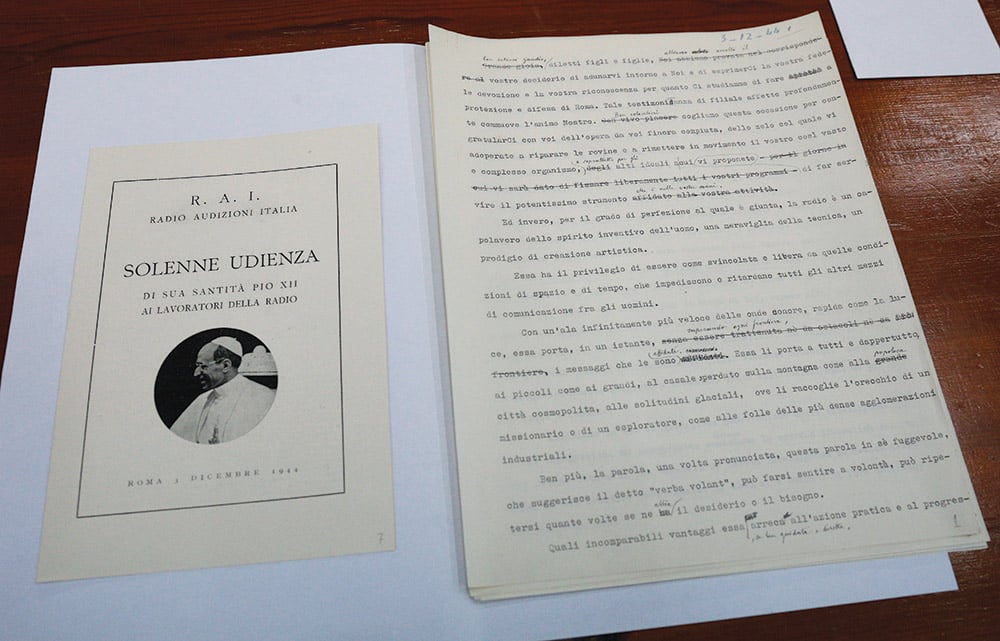

Since March 2, all the documents in the Vatican archives relating to his pontificate are open for consultation by scholars who wish to study the history of the Church and the Vatican during that period.

While some call for Pius XII’s cause for canonization to proceed, others say he was “Hitler’s pope,” silent toward the criminal follies of the German Fuhrer.

Many have sustained these accusations against him throughout history. But to put an end to the controversy, there is only one solution: consult the historical sources.

This is what Cesare Catananti did. Catananti is a retired Italian doctor, professor of history of medicine and a former director of Rome’s Agostino Gemelli hospital (where Pope St. John Paul II was hospitalized several times). In addition to the most famous and vast Vatican Apostolic Archives (before known as the ‘Secret Archives’), Catananti told Our Sunday Visitor, “I believe that few knew of the existence of another small archive, and probably no one before me considered it a historical source.”

The archive in question is that of the Gendarmerie Corps of Vatican City State, that is, the Vatican police force — distinct from the famous Swiss Guards who are responsible for protecting the pope. This force has just celebrated its 200-year anniversary.

“On that occasion,” Catananti said, “the authorities of the Holy See granted me and Sandro Barbagallo [the expert of the Vatican Museums’ modern collections] an extraordinary permit to access that archive.” Thus a book was born on the Gendarmerie’s history.

“That research,” he explained, “provoked in me immense curiosity and interest regarding the Vatican and some themes of the Second World War.”

Position of the Vatican

Catananti’s recent book, which has yet to be translated into English, is titled “The Vatican in the Storm” (Il Vaticano nella Tormenta), given that for the Holy See, the years of the Second World War were really hard times, to say the least. Pope Pius XII was elected on March 2, 1939, just six months before the war began.

Catananti’s recent book, which has yet to be translated into English, is titled “The Vatican in the Storm” (Il Vaticano nella Tormenta), given that for the Holy See, the years of the Second World War were really hard times, to say the least. Pope Pius XII was elected on March 2, 1939, just six months before the war began.

The book’s protagonists are the pope, cardinals and high-ranking bishops and ambassadors. Then, alongside the Vatican gendarmes — policemen — and various people around the Vatican, the Allied soldiers fled from prison camps, and the German deserters were welcomed inside the Vatican walls. Between the small sovereign state’s duties of neutrality and mercy, the latter took priority.

The stormy winds, says the author, were blowing impetuously on the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica from different directions. “On the domestic front, there were heated controversies over the relationship with fascism and asylum to be granted or not, to those seeking refuge in the Vatican” Catananti said.

“There was the dramatic question of the challenge to the Third Reich, which after Sept. 8, 1943, when Italy was invaded by Germany, bordered directly with the Vatican. It should not be forgotten,” he points out, “that the Vatican was (and is) an enclave within Rome, totally dependent on Italy for essential services (water, electricity, transport) And therefore, it was under constant blackmail, if you will.”

A chapter full of anecdotes shows how the ambassadors accredited in the Vatican by countries at war with Italy were forced for this reason to leave their residences in Italian territory, in the center of Rome, and find hospitality (not always very comfortable) inside the Vatican walls. “The Holy See”, Catananti writes, “was between two fires. The Italian government, concerned that enemy diplomats would carry out espionage activities from within the Vatican for the benefit of their countries, demanded strict control from the Vatican over the lives of diplomats. Instead, they, accustomed to another kind of life, honors and privileges, could not stand the strict vigilance of the gendarmes and the restrictions to which they were subjected, therefore they argued with the Secretariat of State.”

One of them, Harold Hilgard Tittman Jr., was the U.S. representative to the Vatican. “His memoirs,” Catananti recounts, “are full of anecdotes about the complicated life of that period. His family, thanks to a series of fortunate circumstances, however, enjoyed a truly privileged logistical accommodation. A building all for them. And according to some sources Tittman did not disdain to make intelligence firsthand. Pretending to be a tour guide in St. Peter’s Basilica, he passed on encrypted information which then flew to Washington. “

The freedom of this tiny state frightened many, and therefore, everyone was trying to find out what was going on inside those solemn but narrow walls. “Everyone was spying on everyone,” Catananti explains. Even the barber of the Gendarmerie, at the end of the war, will prove to be an informant being paid by Italian police.

The “storm,” above all, raged for the nine months (Sept. 8, 1943-June 4, 1944) of the Nazi occupation of Rome. The real risk was that Hitler gave the order to invade the Vatican and capture the pope. Since this event was far from theoretical, Catananti discovered the pope’s defense plan, the existence of which was unknown thus far, written and kept in the Archive of the Gendarmerie. But the use of weapons, after a thorough reflection, was excluded. “The Secretariat of State did not want weapons to be used. Instead the plan spoke of resisting — passive but energetic resistance — with fire hydrants. Then, with progressive setbacks around the apostolic palace, gendarmes and noble guards would shield the pope, in order to protect him from harm,” Catananti wrote.

Aftermath of the storm

Finally, the story tells, the storm passed, but Pope Pius XII was left with the reputation of being a silent and complicit pope toward Hitler’s criminal intent.

This, however, Catananti explains, is not the reality, as demonstrated by the documents from the Gendarmerie’s archives.

“Pius XII preferred to act rather than speak,” Catananti underscores. “Although not having new elements, the idea that I made based on all my research is that Pius XII preferred action over words. … Cardinal Domenico Tardini, when serving as Substitute of the Vatican Secretary of State, as early as the mid-1930s, defined him as ‘silent as a statue.'”

Pius XII preferred working behind the scenes, Catananti suggests, “to avoid worse evils.”

“With Hitler’s madness,” he stresses, “one could not joke. I realize that his silence is not easy to understand and justify by those who paid certain prices. But I believe that Pius XII had adopted, by rational choice, an underground strategy of war on Nazism. Even the German resistance asked him for this silence.”

While a small part of these archives was regrettably destroyed in the 1970s when the building that holds the archives flooded, the surviving documents still speak volumes.

Deborah Castellano Lubov writes from Rome.