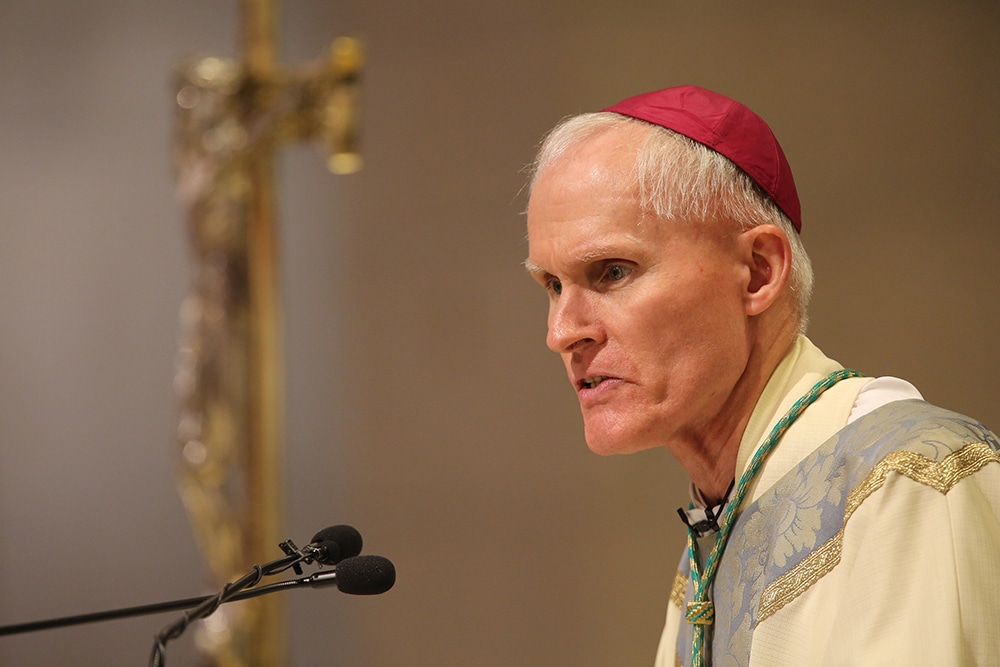

Using a baseball analogy, Bishop Mark E. Brennan of Wheeling-Charleston, West Virginia, said he feels like he went “3 for 4 at the plate” with what the Vatican ordered his predecessor to do in making amends to the faithful.

“It’s still a rather remarkable decision by Rome to insist that a bishop make amends for some of his misconduct in a diocese,” Bishop Brennan told Our Sunday Visitor a few days after he announced in late August the approved “plan of amends” for Bishop Michael Bransfield, who resigned in September 2018 amid scandal.

The Washington Post, which obtained a copy of the Church’s internal investigation of Bishop Bransfield, reported last year that investigators found that he spent more than $2.4 million traveling the world, often in private jets, and that he gave hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash gifts to Church leaders. The money was reported to have come from diocesan accounts.

In their report, investigators detailed an alleged “decades-long campaign of predatory behavior” that began as far back as 1982 when Bishop Bransfield was a priest assigned to the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington D.C. He is alleged to have abused alcohol and prescription drugs, which the report said “likely contributed to this harassing and abusive behavior.”

The Vatican’s Congregation of Bishops ordered Bishop Bransfield, 76, to reimburse his former diocese more than $400,000 in Church funds that officials said he used for personal expenses. Also, he will receive a reduced monthly stipend in retirement. The Vatican further ordered him to publicly apologize for the scandal he caused.

“I don’t recall any other examples of something like this happening to a bishop, at least in this country,” Bishop Brennan said of the sanctions against his predecessor.

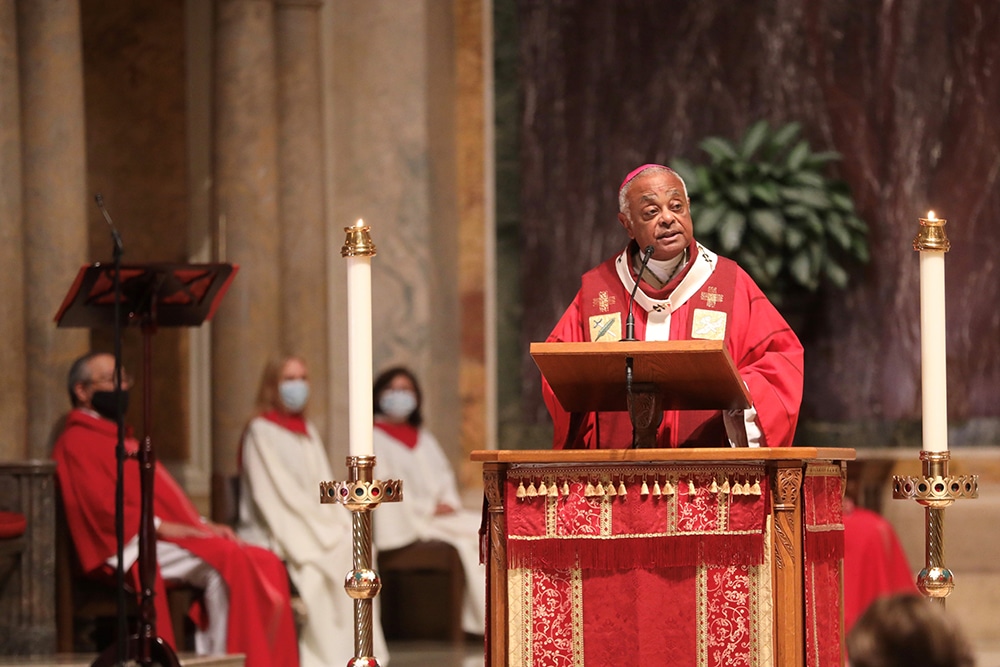

An investigation overseen by Archbishop William E. Lori of Baltimore last year found that Bishop Bransfield, in his 13 years as head of the Church in West Virginia, spent millions of dollars in diocesan money to pay for a lavish lifestyle that included private jets, jewelry, alcohol, luxury goods and overnight stays in five-star hotels. The investigation also found that the bishop had sexually harassed and coerced priests and seminarians in his diocese.

Bishop Bransfield has denied those allegations. In his Vatican-mandated public apology letter, the bishop maintained his innocence, writing that he still believes every reimbursement he received from the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston during his tenure was “proper.”

The defiant tone of his Aug. 15 letter, where Bishop Bransfield said he was “profoundly sorry” if anything he said or did had caused others to feel sexually harassed, struck many observers as insincere, including Bishop Brennan.

“It’s not a true apology. He’s not accepting responsibility for his actions. All you can say is that it’s a non-apology in the form of an apology, and I’ll make that known to Rome,” said Bishop Brennan, who was installed as bishop of Wheeling-Charleston in August 2019.

Bishop Brennan said his predecessor rarely communicated with him and never proposed his own plan to make amends to the flock. Bishop Brennan added that the “non-apology” will not help heal the local Church’s wounds.

“I think people expected him to come forth and say, ‘I’m genuinely sorry for the scandal I caused the diocese and for the people I’ve hurt,'” Bishop Brennan said. “He really didn’t assume responsibility for his own actions, but that’s how I found him all the way through this process. He maintains his complete innocence, and that he’s the victim of other people’s machinations against him. Well, that doesn’t fly with people. They can see through that.”

Per the Vatican’s instructions, Bishop Bransfield paid back his former diocese $441,000 for Church funds officials said he used for his own personal benefit. Bishop Brennan said he waited to publicly announce that detail until the “check had cleared.”

“Trust but verify,” he said.

In retirement, Bishop Bransfield will receive a little more than $2,250 a month, which is about one-third of the $6,200 package usually given to a retired bishop.

“I felt in light of all he had spent on himself, he shouldn’t get a full retirement package,” said Bishop Brennan, who had originally proposed that his predecessor receive the $736 monthly stipend that a regular retired priest with 13 years of service would be paid.

Bishop Brennan had also sought his predecessor to pay back nearly $800,000 to the diocese, an amount that didn’t include a $110,000 penalty Bishop Bransfield reportedly owed the Internal Revenue Service for diocesan money he was alleged to have used for personal expenses from 2013 to 2018.

Though his predecessor didn’t have to pay back the full requested amount and will receive a higher retirement benefit than originally proposed, Bishop Brennan said he was “OK with what Rome said the bishop must do.”

“His retirement package ends up being about one-third of what a bishop who retired in good standing would get, and that certainly is a significant reduction,” Bishop Brennan said. “Imagine if you only got one-third of your pay. That’s a big cut.”

Bishop Brennan said he knows people are disappointed with various elements of the Vatican’s order, but added that he is now focused on moving on, “being a faithful bishop” and restoring trust between the Church and the lay faithful.

“There’s a lot of work to do in West Virginia,” Bishop Brennan said. “We need to evangelize people we’ve never had, win back Catholics we’ve lost, and build up a church and a state that is losing population. It’s tough, but we can do it. We can’t get stuck in the past.”

Brian Fraga is a contributing editor for Our Sunday Visitor.