What was the pro-life movement like before the Supreme Court transformed American politics with its ruling in Roe v. Wade? This question would stump most people, including many pro-life activists.

Generally, most people associate the pro-life movement with the rise of the religious right and the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. But ignoring the history of the movement before that era obscures how the movement changed over time; whether those changes were positive, negative or a mixture; and what lessons pro-life activists can draw on to build a stronger movement that delivers genuine, sustainable results.

Daniel K. Williams’ book “Defenders of the Unborn” (Oxford University Press, $31.95) thus is essential reading. It is one of the most valuable books written on the pro-life movement, and its focus is on the movement before Roe v. Wade.

In an interview on the book, Williams explained that the roots of the movement are on the left rather than the right: “The modern American pro-life movement, which originated in the mid-20th century, was the creation of Catholic Democrats, most of whom subscribed to the social ethic and liberal political philosophy of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. They believed that the government had a responsibility to protect the rights of minorities and provide a social safety net for the poor. They viewed the unborn as a minority deserving of legal protection, but many of them also believed that the federal government had a responsibility to provide maternity health care for women facing crisis pregnancies. In their view, the pro-life movement was a social justice and human rights cause.”

Where the left went wrong

At a time when social libertarianism is so strongly embedded in the Democratic Party, particularly among Democratic Party elites, it is perhaps shocking to hear this history. What happened? How has the party changed so much?

Williams describes a conflict between two strands of rights-conscious liberalism: “The pro-choice movement argued that women had an absolute right to bodily autonomy and equality, and the pro-life movement argued that the fetus had an absolute right to life. In that sense, the debate over abortion was a conflict between two groups of rights-conscious liberals, each of whom emphasized a different inviolable individual right.”

Williams describes a conflict between two strands of rights-conscious liberalism: “The pro-choice movement argued that women had an absolute right to bodily autonomy and equality, and the pro-life movement argued that the fetus had an absolute right to life. In that sense, the debate over abortion was a conflict between two groups of rights-conscious liberals, each of whom emphasized a different inviolable individual right.”

But might this also represent a battle between communitarian progressives, who emphasize things like solidarity and the common good, and contemporary liberals, who emphasize individualism, autonomy and choice? Williams thinks that it does: “The historic roots of the pro-life movement’s social ethic were the Catholic social teachings of the early 20th century, which were grounded in communitarian notions of social responsibility. By contrast, the Supreme Court’s abortion rights ruling in Roe v. Wade was grounded in an argument for individualistic autonomy — a notion that appealed to many 20th-century liberals, but that doesn’t take into account the notions of collective social responsibility and communitarian values that informed the New Deal, the Great Society and many of the social justice campaigns of the last century.”

This battle helps to explain the fractured nature of the current Democratic Party. While pro-abortion Democrats have seized control of the party’s structures of power, between a quarter and a third of all Democrats remain pro-life, excluding the millions who have left the party precisely over this issue.

As each major party has become more ideologically pure through a broad process of ideological sorting, progressivism, in its broadest sense as the heir of New Deal liberalism, is more divided on abortion and a few other critical issues than contemporary conservatism. As it moves toward extreme socially libertarian positions, Democrats of a more communitarian nature feel alienated and excluded. The party’s current woes — it’s in its worst shape since the 1920s — are partly explained by these developments.

A changed movement

But it is not just the Democratic Party that has been transformed by the changing politics of abortion. The movement itself has changed dramatically. One can’t help but think of what the movement might look like today if it had not become so closely aligned with the religious right and the Republican Party.

| Outside the Box |

|---|

|

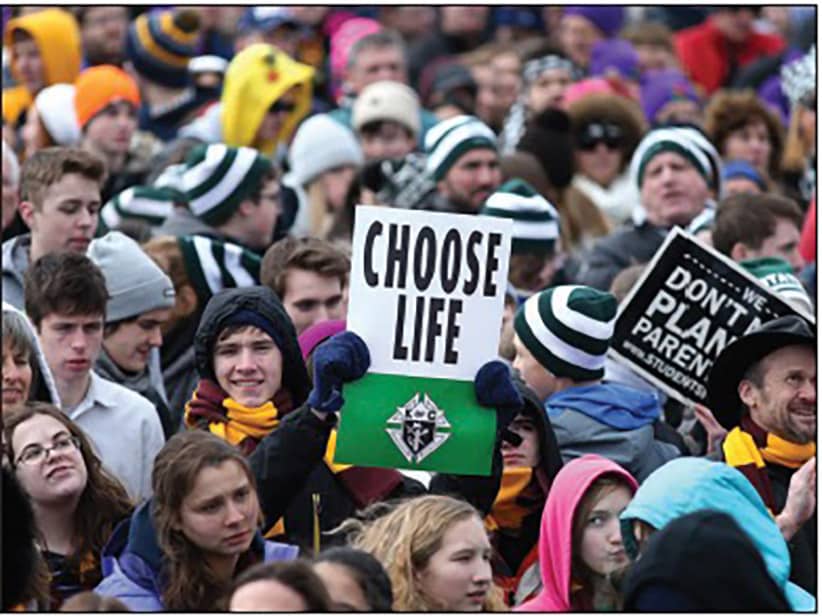

The pro-life movement has seen an advent of young activist groups that defy easy categorization in the polarized climate of U.S. politics. In January 2016, some such groups were barred from co-sponsoring the Women’s March on Washington due to their anti-abortion stance.

– Rehumanize International (formerly Life Matters Journal)

– New Wave Feminists

– Secular Pro-Life

– Feminists for Life

– Consistent Life Network

|

Williams says, “This conservative alliance has sometimes made it difficult for pro-lifers to persuade people outside their movement that they genuinely care about women’s health and human life outside the womb. It was not so difficult for pro-lifers to do this 45 years ago, in the early 1970s, because at that time some of the nation’s leading pro-life advocates were speaking out in favor of maternal health insurance and increased governmental assistance to the poor and the disabled. If the pro-life movement had continued to champion anti-poverty initiatives and governmental programs to provide positive alternatives to abortion, the movement might have been able to remain a bipartisan, politically independent movement with broad appeal to liberals as well as conservatives.”

But the lack of bipartisanship is not solely the result of the strategic calculations of the movement’s leaders. Williams explains, “If one is tempted to criticize the pro-life movement for abandoning its earlier progressive ideology, it is also important to note that the primary reason that pro-lifers abandoned their progressivism was not because they suddenly found New Deal liberalism objectionable, but rather because the Democratic Party refused to support their cause. In other words, most pro-life advocates of the late 20th century would have said that they did not leave the Democratic Party; the Democratic Party left them.”

Williams describes the advantages and disadvantages of the movement becoming closely aligned with social conservatives and their other priorities: “Beginning in the 1980s, a number of pro-lifers — especially conservative evangelicals, but also many conservative Catholics — linked their cause to broader campaigns for sexual responsibility, which, in their view, meant abstinence for unmarried people and faithful, monogamous relationships for heterosexual married couples. The advantage of this approach was that it may have addressed some of the larger structural causes of abortion. But the disadvantage was that it made the pro-life cause less attractive to people who were not social conservatives.”

Ultimately, he says, “The pro-life movement needs bipartisan support in order to achieve its long-term goals; it is not in the movement’s best interest to be entirely dependent on the support of a single party.”

What could be

Linking the movement to conservatism has also had ramifications in terms of the strategy of securing constitutional rights for unborn children. Williams notes that “before 1973, pro-life lawyers universally argued that the 14th Amendment did protect the unborn, and they hoped that the Supreme Court would declare that the unborn had an inviolable constitutional right to live — thus making abortion illegal nationwide.”

But once the movement became aligned with conservatism, the goal was to overturn Roe by placing conservative justices on the bench — those who typically believe that the issue should be returned to the states. This means that were Roe to be overturned by such justices, rather than on a different interpretation of the 14th Amendment, large states like California and New York might still have permissive abortion laws that permit widespread abortion.

Is there hope for a bigger, stronger movement going forward? Williams says, “Many pro-lifers of the late 1960s and early 1970s argued that the legalization of abortion would lead middle-class people to devalue the poor.” Poverty and abortion were linked in the minds of these pro-lifers. Williams states, “Pro-life advocates wanted to help the poor by providing them with the material assistance to care for their children, not by encouraging them to terminate their pregnancies.” Will more people come to see how these issues are linked and believe that abortion is no substitute for real social and economic justice?

If any religious figure can change the status quo, it is Pope Francis, who has denounced both poverty and abortion as part of a throwaway culture. If Catholics and people of good will recognize the integral unity of Francis’ message, perhaps a new generation of pro-life activists can revive some of the movement’s strongest arguments and lead it to a brighter future that transcends partisanship.