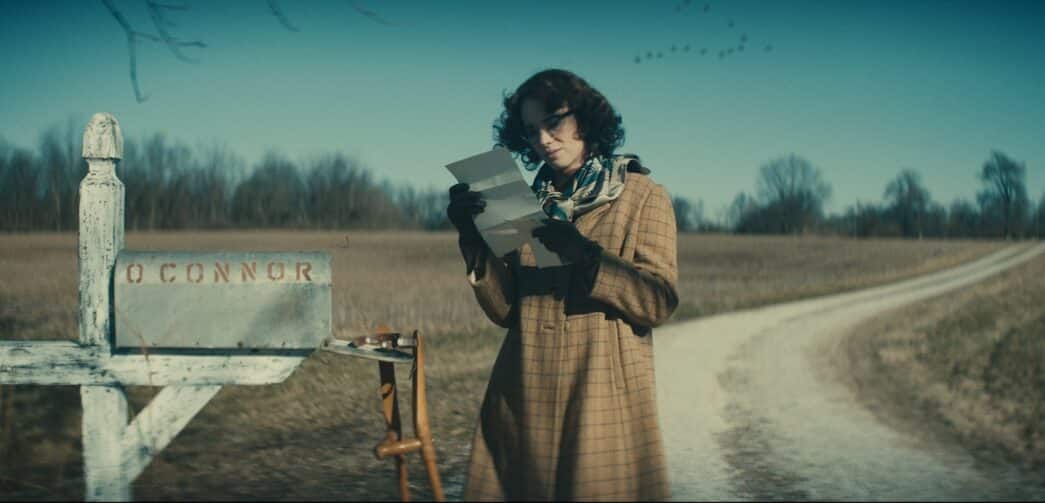

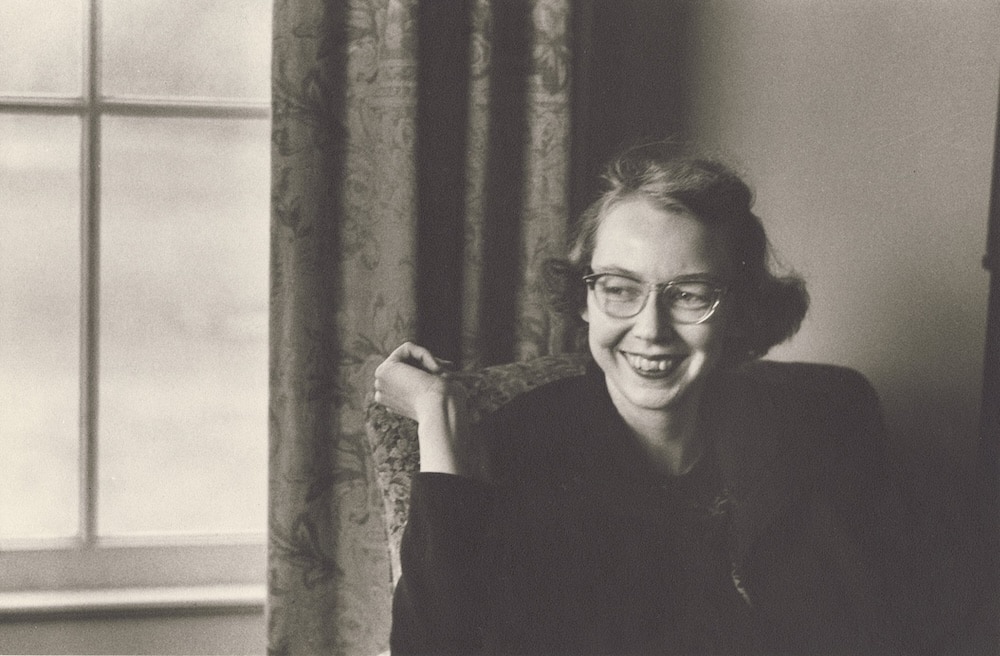

Last May, Maria Wiering published a very fine article about the development and production of “Wildcat,” an experimental film about the life and fiction of Flannery O’Connor. The article included highlights from an interview with Ethan Hawke, the writer, producer and director of the film, which stars his daughter, Maya Hawke, both as O’Connor and several characters from her stories.

Wiering properly pointed out that the production of “Wildcat” is an example of the enduring importance of O’Connor, as well as the persistent challenge of interpreting her novels and stories. In supporting her piece, Wiering cited several other scholars and recent works that wrestle with O’Connor’s legacy. Her insightful article is not a review of the content of “Wildcat,” but rather a thoughtful account of the film’s place in this recent resurgence of interest in O’Connor’s life, work and legacy.

Admittedly late to the party, I recently watched “Wildcat,” after reading several reviews of it, from effusive to dismissive. Put me in the latter camp.

An indecipherable film

I viewed the film with a presumption that it would be a thoughtful interpretation of O’Connor’s life, letters and stories. Alas, however, “Wildcat” is a wild mess. The actors are miscast and do not seem to understand their roles, as though they have not read the stories. Thus, the characters in the film do not resemble those that O’Connor created. From Ruby Turpin and Mary Grace in “Revelation” to Parker in “Parker’s Back”; from Hulga and Manley Pointer in “Good Country People” to Mr. Shiflett in “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” none of the principal actors communicate the viscerally evocative characters of the stories. And the very brief appearance of The Misfit from “A Good Man is Hard to Find” is an utter disaster. Nor is the depiction of Flannery’s mother, Regina O’Connor, anything like the clueless eccentric that Flannery portrays in the many references to her in her letters.

Moreover, the poorly conceived scenes in the movie are a disjointed and jumbled tableaux of excerpts from the stories, without any apparent narrative thread tying them together. If one has not read the stories and letters, one would not have the slightest idea what either are about. O’Connor’s stories are hard to interpret. “Wildcat” is indecipherable.

A lack of spiritual depth

In her article, Maria Wiering cites Ethan Hawke’s observation that the film contains “difficult subject matter for a lot of people. They don’t know what to make of it.” Among the reasons some people don’t know what to make of it is Hawke’s inability to articulate the message of O’Connor’s stories, and his misunderstanding of O’Connor herself. “I am a very spiritually minded person,” says Hawke. “It’s the most important thing in my life. And I don’t see much of it in film.”

Apparently, Hawke thinks he saw a kindred soul in O’Connor. But O’Connor was not a “spiritually minded person.” She was a Catholic Christian in the fundamentalist South. The phrase “spiritually minded person” would have caused her to react as she did when someone suggested that the Eucharist is merely a symbol: “to hell with it.” If told that her novels and stories were about nothing more than “spiritually minded people,” she would have considered her art a failure. The stories are about the “appalling strangeness of the mercy of God,” as Graham Greene put it in his novel “Brighton Rock.”

You would not learn that by watching Hawke’s film. In fact, you would “learn” nothing about O’Connor but that she was a surly, resentful, lovelorn malcontent, wallowing in self-pity about the illness — lupus — that would take her life at the age of 39. She was none of those things, as her letters make very clear. And while the film is strange, the mercy of God — indeed God himself — is entirely missing. One might conclude, consistent with Hawke’s mawkish description of himself, that the film is “spiritual but not religious.” Unfortunately, it does not even meet that very low bar.

I sat down to watch “Wildcat” in eager anticipation that it would be a meditative film, probing the depths of the brilliance of the “Hillbilly Thomist,” as O’Connor described herself. Unfortunately, it is not much more than an Ethan and Maya Hawke vanity project, almost entirely devoid of the transcendent grace of O’Connor’s ingenious fiction.