“What good is it … if someone says he has faith but does not have works?” asks the Epistle of St. James. “Can that faith save him?” (Jas 2:14). One implication of this rhetorical question is that authentic faith will necessarily yield good works. The grace imparted by our faith in the Risen Lord supplies both the means and the motivation to perform spiritual and corporal works of mercy. “I will demonstrate my faith … from my works,” the author declares (Jas 2:18). Works are a kind of proof of faith.

In the Catholic tradition, we also understand that good works are a means of developing, exercising and growing into one’s faith. The author of the epistle uses Abraham as the paradigmatic example of this. Abraham’s works were not in addition to his faith but a necessary aspect of it. “You see that faith was active along with his works,” explains St. James, “and faith was completed by his works” (Jas 2:22). Abraham’s works breathed life into his faith — they animated it. Thus, the epistle famously declares: “faith … if it does not have works, is dead” (Jas 2:17).

Put another way, in the context of Christian faith, works themselves are grace-receiving and grace-bearing. Because of the merits of Christ, works convey grace both to the recipient of good works and to those who perform them. Works of penance after confession are the most obvious example of this dynamic, intimate, inseparable relationship between the faith and works that, together, bear salvific grace. Jesus, himself, affirms this relationship as recorded in the Gospel of St. Matthew: “Whatever you did for one of the least brothers of mine, you did for me” (Mt 25:40). The context both in the Gospel and the epistle, of course, is the death and resurrection of Christ. The gratuitous work of Our Risen Lord makes it all possible.

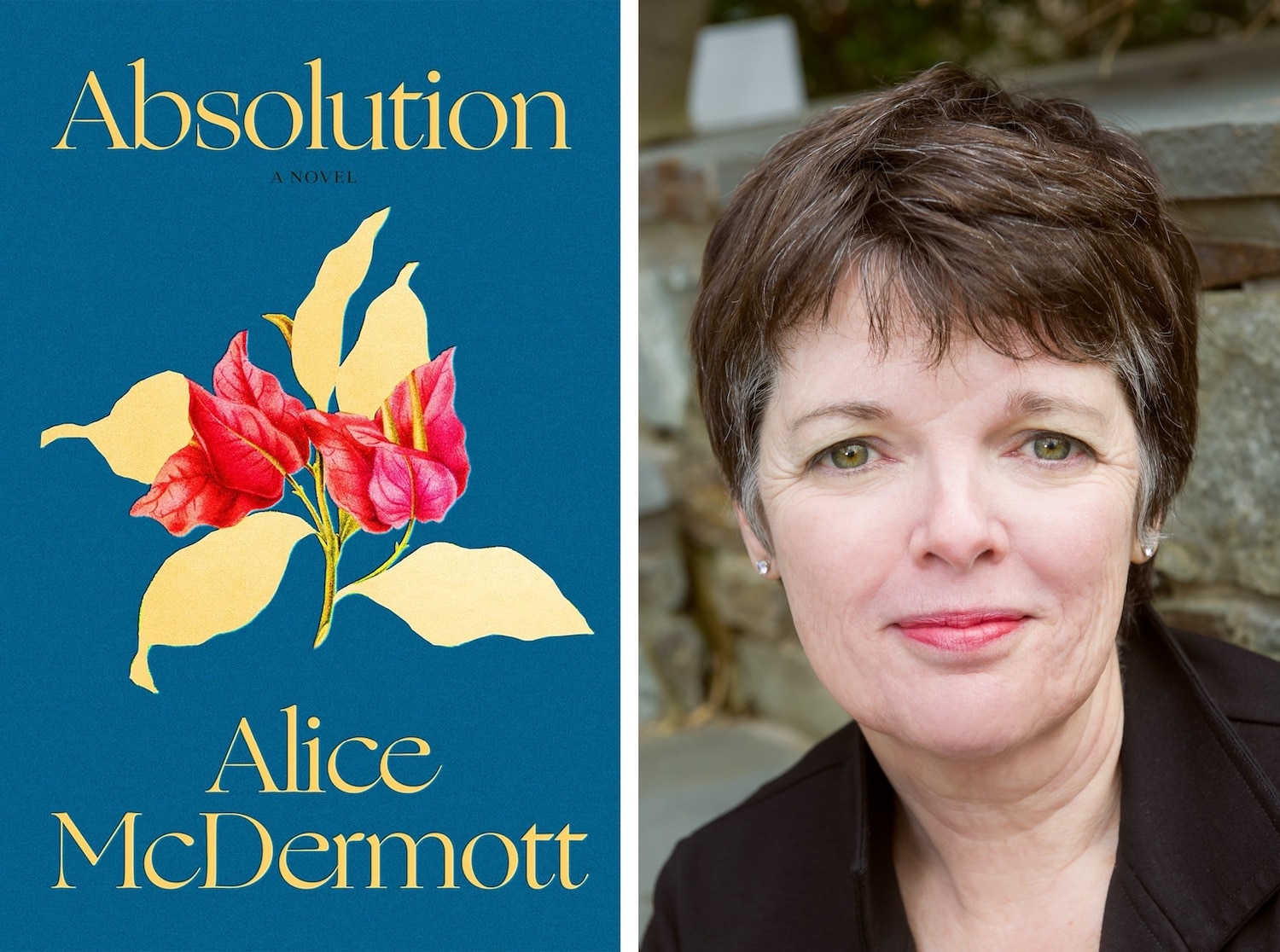

Questions explored in ‘Absolution’

But what if one has works but not faith? Or what if one’s “works” become so misdirected that they lose their connection to faith? Can that save one? Can we be absolved of our sins by works alone — even if they are good works — apart from the faith by which we receive and affirm God’s grace? These are the questions posed and explored by Alice McDermott’s splendid new novel, “Absolution.”

McDermott has already established herself as one of America’s foremost Catholic writers in such novels as “That Night” (1987), “Charming Billy” (1998) and “The Ninth Hour” (2017). Creating complex characters and relationships, and vividly setting them in and around her native Brooklyn (and Long Island, more generally), McDermott evokes John Cheever’s acute sense of place. But McDermott’s particular Catholic sensibility is evident through characters that are more introspective than Cheever’s and through moral quandaries that probe more deeply. With “Absolution,” McDermott brings these qualities together in what may be her masterpiece.

“Absolution” is an epistolary novel, composed as an exchange of letters between two women whose lives crossed briefly and unremarkably, but were linked by a third person whose dynamism and dominance made a lasting impression on both. The exchange is between 80-something Patricia and 70-something Rainey, recounting their brief time living in Saigon some 60 years earlier, at the beginning of the American involvement in the war. The subject of the exchange is Rainey’s now-deceased mother, domineering Charlene, who was newly-wed Patricia’s best friend when Rainey was a pre-adolescent girl.

Justifying the means to an end

Charlene was a whirlwind of frenetic social organization for the American expats and indefatigable charitable works for the poor and displaced nationals in and around Saigon. Her principal charitable endeavor was to (illegally) import Barbie dolls, and either resell them on the black market to raise money for her charitable endeavors, or to give them to Vietnamese orphans or other dispossessed children. These efforts included brave, if not reckless, trips to a local leper colony, which was forbidden and dangerous.

Much as Patricia admired Charlene’s energetic works, something never seemed quite right about them. A nominal Episcopalian, Charlene was neither motivated nor consoled by religious faith, but rather by something that Patricia could not quite name. Charlene’s good works, in other words, seemed to be disconnected from any context that Patricia — who, with her husband was a faithful, Mass-going Catholic — could understand. Charlene believed that any and every means, regardless of how sketchy, could be justified by the alleged good end that she sought to achieve. Charlene, thought Patricia, was seeking absolution for something. But she — Charlene — neither knew what it was or how to achieve it. She had works but not faith.

This conflict culminated in a heart-rending occurrence near the end of Patricia’s stay in Vietnam, shortly before she left with her husband to avoid the escalation of the war. It would spoil the novel to reveal the incident, but it both revealed Charlene’s desperate need for absolution and her misguided efforts to obtain it. More importantly, the incident tends to answer the question that McDermott poses in the structure of the novel: Are works without faith dead? As Patricia narrates their time in Saigon, and as Rainey responds to fill in the years after their return to the U.S., McDermott takes us through an enriching and graceful consideration of just that question.